America, Land of the Feathered Serpent (5 of 6)

Part 5: America's Fight with the Shadow (Part 2)

30. Church, Crown, and Bank: the Three-Headed Shadow from Europe

As we discussed in previous articles of this series, the American lineage of civilization - including the Inca of Peru, the Mayans and Aztecs of Central America and Mexico, and the nomadic tribes of North American Indians - all emerged and rose to prominence without use of a monetary system.

Instead, the great empires of the western continents were socialist in nature, with their domestic economies organized centrally by an administrative bureaucracy rooted in the temple.

Leveraging their possession of esoteric knowledge concerning astrology and alchemy, the priesthood organized and ordered society according to their own mysterious formulas.

This governance model is similar in spirit to the way the Atlantean Empire once functioned during its golden age, with its sorcerer-magicians ruling the populace top-down with near total control.

This connection in economic governance models between Atlantis and America makes sense, as the early American empires were founded by migrants who were descendants of survivors from the destroyed Atlantean Empire.

On the Eurasian continent, civilization developed in a very different direction compared to its counterparts in America.

Unlike America, the empires of Eurasia developed - and became increasingly dependent on - the core institutions of capitalism, including credit, debt, money, and private property.

The lasting effect that these capitalistic institutions had on Eurasian civilization was to: push society in a secular direction; shift economic management out of the hands of public administrators and into private control; and support the rise of a powerful oligarchical pattern of rulership.

In short, capitalism created a class of secular, privately wealthy, politically self-interested individuals. These in time conspired together to establish oligarchy, with the wealthy aristocratic class taking over political governance of society, steering it toward a pattern that serves its own interests while sacrificing the overall health of society as a whole.

To reemphasize, the institutions of finance, accounting, credit, debt, and money were invented and brought into use only in Eurasia; they had no counterpart in the Western Hemisphere.

Likely, this was intentional: the great empires of the Americas were founded as deliberate experiments in non-capitalistic forms of economic organization.

The Inca and Maya civilizations serve as two prominent examples of this: each formed massive empires with complex economies connecting millions of people and did it without relying on the core institutions of capitalism.

As a consequence of its reliance on capitalistic institutions, over time, across Eurasia, the economic administration of society fell increasingly into secular control, moving out of the temple and into the hands of the state. Then, from out of the hands the state, political power would shift again, moving instead into the hands an aristocratic oligarchy.

In the history of Eurasia, the rise of oligarchy, and the subsequent decline of monarchies, is intimately connected with its reliance on the institutions of capitalism. Here, we find the institution of monarchy succumbing to the rise of a class of merchant-banker capitalists, who conspire with corrupt state officials, mercenary armies, mining interests, and slave traders to take control of society and reengineer its domestic economy to suit their private interests.

Perhaps the hallmark example of this is with Rome: the financial oligarchy that gained control over the Roman Empire, before eventually destroying it, was characterized by these features. Ultimately, the unrestrained corruption of the Roman oligarchy brought about the Empire’s final demise: it was their wealth-addicted aristocracy that gained political control over the state, mismanaged their societies, corrupted their cultures, weakened their institutions, enslaved and disenfranchised their people, and left the empire vulnerable to outside invasion and internal rebellion, both of which eventually took place.

During the Axial Age, capitalistic oligarchies such as Rome’s emerged as personifications of “the Collective Shadow”.

Consequently, in relation to the Mystery Schools, they performed the role of “Tezcatlipoca”, the archetypal “Adversary” who embodies the destructive power of entropy.

Taking on the properties of entropy, the eternal adversary of life, they preyed upon the psychological weaknesses inherent to pagan civilization, systematically destroying and deconstructing it, breaking the compound apart so that, from its base elements, a new institutional order could be constructed.

After the collapse of pagan civilization, these capitalistic oligarchies went dormant for a period, their power base having been destroyed.

In their place emerged a new Adversary for the esoteric schools: the Roman Catholic Church, which fought tooth and nail to eradicate the remnants of the old pagan Mysteries (the Manichaeans and Templars being the two most prominent examples of this), seeking instead to enforce their own theocratic dogmas upon the minds of the masses.

Eventually, alongside the Church, a second adversary emerged: the feudal lords and monarchs of Europe. These tyrannical rulers, working in conjunction with the Church, were the primary “Adversary” of the Mystery Schools during the Middle Ages.

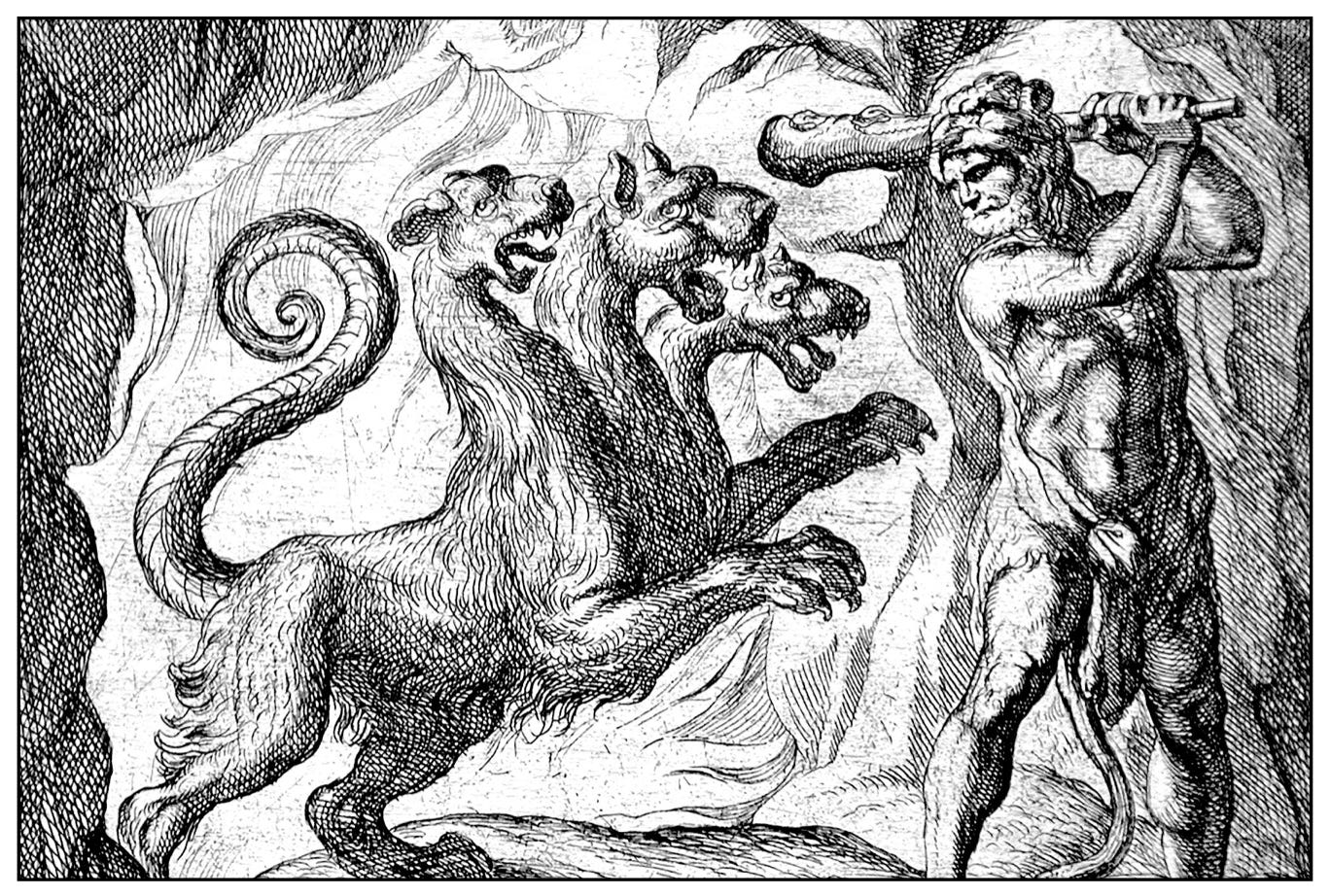

Later, over the course of the Middle Ages, gradually a third “Adversary” would emerge, joining the other two to form a formidable three-headed monster. This third “Adversary” was the return of the old capitalists to Europe.

After a period of dormancy, the capitalist dynasties from fallen Rome re-emerged through the powerful merchant-banking cartels of Venice and North Italy.

Through these oligarchs, the capitalist model that once dominated Rome would spread back out to re-infect Europe once again, giving the Mystery Schools a third Adversary to confront and overcome in their grand quest to establish a worldwide “Philosophic Empire” based upon democracy.

Together, the crowns of Europe, the Roman Catholic Church, and the merchant-banking capitalists constituted a three-headed Shadow monster, a personification of the “Adversary” made manifest in European society.

By the time the age of exploration and colonization commenced during the 15th century, Europe’s three-headed “Tezcatlipoca” had grown strong and could no longer be contained to its home content.

After Europe’s rediscovery of the American continents, the Church, monarchs, and capitalist oligarchs all competed to gain traction and influence in the virgin lands of the West. Together, these three imperial institutions conspired to claim the entire Americas as a vassal colony of their own.

With the coming of the Conquistadors to the Americas, this three-headed “Shadow” was officially imported into the West, infecting its lands and destroying its native populations.

Later, after the founding of the democratic republic in North America (the United States), the Church and crown would recede as dominant geopolitical forces, with the capitalist oligarchs instead rising to take control as the dominant Adversary set against the Esoteric Schools.

The ascendency of the European oligarchs in their bid to take political and economic control over the United States culminated in the founding of the Federal Reserve in 1913.

Ever since, the US has fallen under the political and economic control of a powerful oligarchy comprised of private banks, corporate interests, and military-intelligence officials. This oligarchy remains with us; today, we are still battling to liberate ourselves from its control.

31. The Playbook of the Capitalist Oligarchs

Banking, like all social institutions, begins in the Temple.

All social activity originates in the temple. The separation of the institutions of church and state - and later state and economy - comes only at a relative late stage in human history.

In the original pattern, before any separation had taken place, the priesthood were the custodians of all knowledge. Consequently, in early states, economic and cultural activity was organized under temple oversight, with institutions such as banking becoming independent, secular entities only at a later point in time.

This shift began with the River Valley civilizations around 3000 BC, before later escalating with the wave of Axial Age empires that emerged around 600 BC.

After 600 BC, we find, over time, across Eurasia, the economic organization of societies falling increasingly under secular control, moving out of the Temple’s oversight and into the hands of monarchs and state bureaucrats. Then, once in the secular hands of the state, it shifts once again, falling now into the private control of capitalist oligarchies.

These secular capitalists, with their accumulation of private wealth, schemed to gradually take control of the European content, overthrowing its monarchies and installing capitalist oligarchies in their place.

Here, the traditional administrative functions of the state - banking, trade, war-making, tax collecting - became coopted by private interests. These capitalists conspired together to form an oligarchy, with their ever accumulating reserves of private wealth serving as the basis of their power.

Some of the capitalistic republics formed during the Axial Age, like Athens and Rome, adopted democratic institutions. But these democratic institutions, even in their heyday, were politically subservient to the power of the capitalist oligarchies and their oceans of private wealth.

It was the insatiable greed of this transnational capitalist oligarchy that spurred the endless quest for expansion that characterized the Axial Age empires.

The capitalists brought about their financial empire by means of a privatized “mercenary-coinage-slavery” complex: a debt-fueled war-making machine propelled toward incessant imperial expansion.

The central culprit responsible for driving the ceaseless expansion of the capitalist oligarchs’ financial empire is the magic of compound interest, which grows exponentially.

Due to the unavoidable mathematics of compound interest, the oligarchs’ financial policy of lending money out at usurious interest rates ensured, with absolute certainty, that eventually the entirety of society would fall into an inescapable indebtedness to the capitalist class.

This is true for the simple reason that the amount of natural resources on Earth and the capacity of labor to transform these resources into commodities cannot support existential growth. Consequently, there will always come a time when the economic output of society will fall short of the exponentially growing compound interest on its debt.

The oligarchs take advantage of this situation to both expand and consolidate their power. This they accomplish by strategically managing boom and bust (or expansion and contraction) cycles, which result as a consequence of their lending policies.

During this cycle, in its growth phase, the oligarchs expand the reach of their financial empire by adopting “easy money” lending policies. Then, in the consolidation phase of the cycle, they make money scarce and call in their loans, laying claim to the public and private wealth of society as collateral on the debt owed to them.

Therefore, during boom cycles, the bankers strategically increase the amount of debt circulating in society (i.e. they create a “bubble”). Through the creation of this bubble, the banking cartel ensures that the reach of its financial dominion will expand into new, previously untapped markets.

Next, when these same bankers contract their lending, a wave of bankruptcies inevitably ensues, with the oligarchs seizing control of the land and resources of society as collateral on the debt, further consolidating their wealth and power over the rest of society.

In the meantime, during this contraction phase, the need to keep one step above the incessantly rising tide of compound interest ensures that the populace will resort to increasingly desperate and radical measures to obtain money to service their debt. A “race to the bottom” results, as the populace competes to obtain money, which the bankers have made deliberately scarce.

Over the course of the Axial Age, capitalist empires such as this rose and grew dominant all over Eurasia. This motion culminated with the rise of the Roman Empire, whose oligarchs extended the reach of their empire across Eurasia before seeing it self-destruct under the weight of its own chronic indebtedness.

The financial oligarchs responsible for corrupting and ultimately destroying Rome also went down with the empire they helped destroy.

Replacing them was the Roman Catholic Church, who took the gold and silver currencies that fueled the oligarchs’ capitalist empire out of circulation, parking them instead in the storehouses of the Church and returning Europe to a temple-run credit system.

This situation remained the case throughout most of the Middle Ages, with the capitalist oligarchs kept at bay.

But gradually, with the rise of the powerful merchant banking oligarchies of Venice, Florence, and Genoa, we find capitalism returning to Europe.

Through the work of powerful merchant-banking dynasties based in this region, the core institutions of Axial Age capitalism would be resurrected: notably, the military-coinage-slavery complex that was the hallmark of Rome.

32. An Old Banking Dynasty Resurfaces in Venice

During the mid to late Middle Ages in Europe, a banker-lead oligarchy of capitalist powers reemerged in the city-states of north Italy.

Of these, Venice rose to become the most powerful, gaining monopolistic control over international trade between the Europe and the Near, Middle, and Far Easts.

This is the same model the Roman oligarchs had originally used: they began as merchant bankers who strategically leveraged their private wealth and political connections to take control of the governments and political institutions of Europe.

In his book “Financial Vipers of Venice”, historian Joseph P. Farrell elaborates on the rise of the Venetian bankers, highlighting their connections and similarities to the previous dynasty of Roman oligarchs that once ruled over Europe.

Farrell writes that, following Rome’s collapse, many of its most prominent banking families, notably those connected with merchant banking, fled “northward to the protective lagoons and marshes of what would later become the center of commerce and banking in Western Europe during the Middle Ages: Venice.”

The geography of the region pushed the Venetians to embrace trade and banking: “without land for agriculture, with no visible means of support, no access to commodities of any kind, this location meant that the population of the lagoon turned almost immediately to the sea, and to trade, as the foundation for their commonwealth. The empire that emerged from this circumstance might be said to be the world’s first ‘virtual economy,’ based on a fragile balance of trade in bullion, slaves, commodities, and spices.”

Due to the fragility of its economic security, Venice “lived in perpetual fear that, if its trade routes were severed, the whole magnificent edifice might simply collapse.” Thus any threat, whether geopolitical, military, or (ideological), was inevitably perceived by the Venetians as a threat to their whole way of life.”

Here we find that, like the oligarchs of Rome, the Venetian merchant-bankers developed a competitive and self-serving mindset that lead them to prioritize their own prosperity over the collective health and well-being of the entire society.

Their lack of loyalty to any cause behind their own growth locked them into repeating the same psychological sickness that had plagued the earlier Roman oligarchs. They became wealth-addicted and positioned themselves as a financial parasite over the economies of the various lands they gained control of.

To the Venetians, the only thing that mattered was increasing their own wealth and power at the expense of all others, ”with trade conducted on an ‘amoral’ basis free of religious or (moral) considerations.” Instead, “Venice assumed the right to buy and sell anything to anyone.”

Around the 10th century AD, after establishing a lucrative merchant banking empire in the Mediterranean region, Venice won the privilege of being formally recognized as part of the Eastern Roman Empire. This granted them special trading and tax exemptions throughout the Eastern Empire, resulting in their wealth and power growing exponentially.

Venice became, as a result of their special trade accommodations, an autonomous self-governing city within the Empire, uniquely positioned to dominate trade across the Adriatic Sea.

Eventually, their financial empire would further grow to play a dominant role in the trans-Eurasian gold and commodity trade, with goods flowing west from Asia and gold and silver flowing east from Europe to pay for them.

Acting as an intermediary between the two, the Mediterranean region played a pivotal part in this trade; and as the dominant hegemon in the region, the Venetians positioned themselves to grow immensely wealthy and powerful.

The Venetian merchant-bankers combined their special trade relationship with Byzantium with their connections to the Roman Catholic Church in order to facilitate trade between the eastern and western branches of the former Roman Empire.

This trade was facilitated through the use of bullion (gold and silver), which, having previously been parked in the coffers of the Church, began to emerge once again as a vital economic factor in world affairs.

Joseph Farrell explains how the Venetians came to dominate international bullion trade, becoming “far and away the world’s largest concentrated bullion market at that time.”

“Europe was, at that time, a tapestry of small kingdoms, duchies, and city-states, each with their own coinage, and each system of coinage with its own standards of weight, fineness, bullion content, and so on. Additionally, most of these states were part of a vast trading network flowing (from Europe) through Genoa and Venice into the Middle and Far East, each also with their systems of coinages, weights, fineness, and so on.”

“By the nature of the case, then, Venetian bankers on the Rialto had to be competent at dealing with many different systems of coinage and with exchange rates of gold and silver bullion on a daily basis.”

This made them an indispensable intermediary for trade taking place between Western Europe, Central Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. As a result, the Roman Catholic Church and the European states became increasingly reliant on them, creating the perfect condition for the oligarchy to grow in wealth, power, and influence in each region.

In true oligarchical fashion, the Venetians were loyal to no one but themselves: they soon hatched a conspiracy against the Eastern Roman Empire they had outwardly been serving.

The Venetians were cunning and, piggybacking off the Fourth Crusade, maneuvered the Church and the European monarchies into supporting the sacking of Constantinople (which was not its original target; Palestine was).

In the wake of the Crusade’s sacking of the Eastern Empire’s capital city, the Venetians’ looted its monetary wealth and installed their own puppet government over them. This they then leveraged in trade negotiations with the West, further fueling their rise as a formidable geopolitical adversary in Europe.

By means of their control of the bullion market, a crucial component in trans-Eurasian trade, the Venetians were gradually able to consolidate their political, economic, and financial power over Europe.

The Venetians accomplished their coup over the European monarchs by conducting currency and trade wars and installing puppet regimes, through whom they acquired court systems loyal to their interests, capable of enforcing the debt contracts that empowered the oligarchs and disenfranchised the masses.

The militaries of captured states would be directed by their indebted monarchs to conduct wars whose outcomes serviced not the state or populace as a whole but rather the long-term interests of the bankers and oligarchs.

In retrospect, it is clear that the Venetians rose to power by following the same strategic playbook that their merchant-banking predecessors had used centuries earlier to take control of Rome.

First, they expanded their power and influence by playing states off each other, making each dependent on their financial services to facilitate trade and war.

Then, the bankers leverage this economic influence in order to gain political control over the states. In particular, they sought to capture:

a) The legal systems of their vassal states, which they used to enforce their debt contracts;

b) The right to privatize and monopolize the distribution of money, which they switched from credit to coinage;

c) The right to lend at usurious interest rates; and

d) The power to control and direct the state military (or private mercenary armies hired by the state), which the bankers leveraged to aggressively expand the reach of their financial empire.

After winning these concessions, the bankers caused the various nations they gained influence over to wage war on each other, with the bankers financing both sides. This results in the states becoming further indebted to the capitalist oligarchs, who became correspondingly enriched the more the bloodshed increased.

Ultimately, after war has killed off all opposition, the bankers unite the various states they have gained control over, ruling over them collectively as an economic empire. This is how the Roman Empire was formed, and it is the model that the Venetian oligarchs were hard at work trying to replicate.

33. The Venetian Oligarchy: the Shadow of the Templars

In many ways, the Venetian oligarchies emerged as the “Shadow” of the Templars, particularly with respect to the socioeconomic development projects the Templars were engaged in throughout Europe during the Middle Ages.

As discussed in our previous chapter on Francis Bacon, the Templars’ work was based around resurrecting the old guild system of antiquity. They used these guilds to build markets, promote artisanal values and fair trade practices, and establish other important financial and economic institutions, ones vital to elevating the standard of living of the European people.

For example, the Templars established an innovative transnational credit system. Joseph Farrell describes how it worked, noting that it was built “to help knights transfer their money from one place to another along pilgrimage routes (also used by the Crusades). Travelers could draw on accounts established on an embryonic form of the modern credit card, on the basis of credit to be paid off later, after their return back home. Or, the Templars were able to receive payments in one of their local branches and pay out an equivalent amount in another land, charging an agro fee for this money-changing and transfer.”

The Templars and Venetians shared one goal in common: both were interested in leveraging finance, economics, and trade to weaken the power of the Church and the European monarchies. But each pursued this goal in a different way and each were driven by different values and intentions.

So while the Templars and the Venetians shared some similarities and goals in common, when it came to their long-term social, political, and philosophical visions for society, the two differed markedly.

The Templars were pursuing grand philosophical ideals like democracy and socialism, while the Venetians were after the opposite, namely oligarchy and capitalism.

Here we find the archetype of Quetzalcoatl verse Tezcatlipoca repeating itself, with two competing factions struggling for supremacy in Europe, each pursuing diametrically opposite visions and goals.

The Venetians, as Tezcatlipoca, became the financial equivalent of “black magicians”. Through their selfish misuse of banking and debt, they wrested control over European society and began to steer its institutional order toward an inevitable state of entropic dissolution.

In true Tezcatlipoca fashion, in fulfilling their task, the Venetians preyed upon and fed off of the shadow tendencies latent within European psychology: notably, those of greed, materialism, and ego-centrism.

The Venetians therefore emerge as a “shadow projection” of the European psyche: they exist as a concentrated karmic representation of negative shadow tendencies that had long been festering within the population as a whole, since back before Roman times.

As with their earlier incarnation in Rome, the Venetian oligarchs served as an instrument for spreading and bringing out negative character traits within the populace, such as materiality, wealth addiction, and egotism.

As its “Shadow”, the Venetians embodied the negative psychological baggage of European civilization, in particular its unresolved penchant for falling into a materialistic mode of psychology.

Historian David Graeber further expands on this, noting that “everywhere we see the military-coinage-slavery complex emerge (the hallmark of oligarchy), we also see the birth of materialist philosophies. They are materialist, in fact, in both senses of the term: in that they envision a world made up of material forces, rather than divine powers, and in that they imagine the ultimate end of human existence to be the accumulation of material wealth, with ideals like morality and justice being reframed as tools designed to satisfy the masses.”

The “black magicians” in the banking cartels catalyze the expression of antisocial and self-destructive behavior within the populace as a consequence of their use of the “black magic” of compound interest.

This evil policy creates an ever-rising tide of debt, which forces the population to behave in increasing desperate, selfish, and self-destructive ways to stay ahead of it - with community life becoming correspondingly eroded as result.

In the case of Venice, the heart of their capitalist oligarchy was called the Council of Ten; this is where the psychology of Tezcatlipoca was most deeply concentrated within their society.

The Council of Ten was the elite, innermost body of Venice’s larger “Grand Council”, which was the seat of oligarchy in the Venetian republic.

As Joseph Farrell informs us, membership in the larger Grand Council was restricted to the male members of noble families. At its peak, it numbered around 2,000 members.

This oligarchical institution existed as a “closed caste in the society of the Republic; a caste with its own inner elite” - the Council of Ten.

Membership in the Council of Ten was much more exclusive: it “was restricted to members of the Venetian nobility, elected and chosen by the Great Council, and they never numbered more than ten members who acted in concert directly with the Doge and his six councilors. In other words, membership on the Council of Ten was never more than seventeen people.”

As Joseph Farrell further describes, the Council of Ten, functioned something like an early form of the CIA:

“The Council of Ten served first to coordinate a vast network of spies, both inside of and outside of Venice, extending even to the Mongols. It thus coordinated all counter-intelligence, intelligence, police, and surveillance operations both inside and outside the Republic and its territories. More importantly, it was authorized to decide matters of policy and state in the name of the Great Council, and thus, its decrees had the force of law for the Great Council itself.”

“In other words, the Council of Ten combined both foreign policy, internal security, international espionage, and a law-making capacity in one body. … (They) literally ran all of Venice’s vast intelligence network, a network that stretched from Europe to the Mongol court in Asia. Similarly, it was responsible for all counter-intelligence and police functions in all the territories of the Venetian Republic, and moreover, it acted as an agency of the Great Council, and thus could enact decrees, laws, and policies in its name. In the name of these functions, it not only spied on virtually everyone, but it also received an endless stream of “secret denunciations” and could issue bills of capital attainder, conduct secret trials of anyone so denounced, and, if a death sentence was issued, the Council’s spies would simply round up the individual, and carry out the execution (by strangulation).”

In sum, the Council of Ten, with the Grand Council around them, drove the Venetian empire in its quest to establish a merchant banking imperium across the face of Europe, thereby resurrecting the economic empire of the earlier dynasty of Roman oligarchs.

In their campaign for world conquest, the Italian oligarchs utilized a type of “black magic”: compound interest. This negative, parasitic application of finance results in the concentrated accumulation of resources within the hands a small, aristocratic elite, which then catalyzes the entropic destruction of society as a whole.

In this way, through the Venetian oligarchs, a European version of Tezcatlipoca emerges, seeking to install its brand of financial oligarchy over the face of Europe.

This European Adversary rises as a manifestation of the Collective Shadow, feeding off of the negative attributes of ignorance, superstition, and fear that the population as a whole has allowed to fester within itself.

The banking oligarchs emerge as the karmic embodiment of these negative traits: they are a Shadow we project out of our own weaknesses and imbalances, which they feed off, destroying us in the process.

To prevent our own entropic destruction at their hands, we are forced to confront and do battle with them, and thus, to finally address the weaknesses within ourselves that supported their rise in the first place.

34. The Italian Super-Companies: Instruments of Oligarchy

Like Rome before it, the stability of the Venetians’ financial empire depended on a policy of continuous expansion.

Because compound interest was the fuel that drove the Venetian oligarchy’s financial machine, they were forced to continuously hunt for new opportunities to keep their debt bubble afloat: should it burst, their empire would see the same fate as the Romans.

The need to perpetuate exponential growth is the hallmark of all such banking oligarchies. As David Graeber further explains, “capitalism is a system that demands constant, endless growth … in order to remain viable.”

Its incessant need for growth in turn corrupts human psychology, leading it into a materialistic orientation that quantifies the world, seeing it in impersonal financialized terms.

To facilitate perpetual growth, the Venetian bankers (along with their peers in Florence, Genoa, and other oligarchy-controlled north Italian city-states) innovated several new financial institutions, including fractional reserve lending and the formation of joint stock corporations.

Leveraging these financial institutions, “they created a veritable mercantile empire over the course of the eleventh century, seizing islands like Crete and Cyprus and establishing sugar plantations that eventually came to be staffed by African slaves.” (Graeber)

In this manner, they brought back the old “military-slavery-coinage” complex of the Roman oligarchy. Like the old Roman model, this complex was characterized by: “the organization of slave labor, management of colonies, imperial administration, commercial institutions, maritime technology and navigation, and naval gunnery.” (Graeber)

Graeber notes that, soon after the Venetians adopted these practices, their neighbors in Genoa followed suit: “one of their most lucrative businesses was raiding and trading along the Black Sea to acquire slaves to sell to the Mamluks in Egypt or to work mines leased from the Turks. The Genoese republic was also the inventor of a unique mode of military financing, whereby those planning expeditions sold shares to investors in exchange for the rights to an equivalent percentage of the spoils.”

Here we find that the rise of early corporations are intimately connected with the onset of capitalist oligarchies, who are building their power and wealth off a socially destructive model of slave trading, resourcing mining, and military financing.

Corporations first emerged as instruments of oligarchical empire, in other words; today, they by and large serve the same function.

Upon closer investigation, we find that the rise of the Italian banking dynasties could not have taken place without them: the privatization of finance necessitates the privatization of economic production, with corporations emerging as the product of this shift.

Corporations thus emerge as private economic instruments of the banking cartels, who use them as instruments of economic expansion and political centralization.

Corporations, or, as they were once called, “super-companies”, emerge as “shadow” versions of the guild system that the esoteric orders of Europe were working to develop and promote during the Middle Ages

The intention of the corporations was not to promote artisanship or prosperity, as it had been with the guilds. Rather, they emerged as instruments of power projection: economic weapons of the banking oligarchs.

In his book “Financial Vipers of Venice”, Joseph P. Farrell describes how the Italian super-companies worked. Here, we discover the archetypal form of the corporation first coming into existence.

Farrell begins his analysis of the early Italian super-companies by first citing scholar Edwin S. Hunt’s definition of them: “The medieval super-company is defined here as a private, profit-seeking organization operating several lines of business in a very large volume in multiple, widespread locations through a network of permanent branches.”

Farrell then informs us that “the medieval super-companies were organized as semi-permanent partnerships”, with each shareholder entitled “to a share of profit or loss prorated to the percentage of the total company capital that they contributed to.”

“These partnerships were formed and dissolved entirely at the whim of the partners themselves.”

Delving deeper into the inner governance dynamics of these super-companies, Farrell notes that, “as a matter of course, these medieval super-companies relied upon a careful ‘philosophy of management.’”

“Given the slow nature of communications of the day, this meant that strategic decisions effecting the long-term goals of the company remained in centralized family control, but operational decisions had to be left in the hands of local factors, or “branch managers,” who were trained in the central offices in Florence. In branches of extreme importance, these factors were often members of the founding and controlling family itself.”

“As a further means of retaining familial control over the strategic functions of the partnership, all staffing of the branches was overseen by the central offices in Florence, that is to say by the founding and controlling families. And as a yet further means of retaining control, personnel in the various branch offices and locations were routinely rotated. All of this, of course, also required that the companies maintain consistent intelligence gathering, communications, and courier systems.”

Here, we discover that the super-companies acted as transnational economic entities under the political and economic control of an elite caste of oligarchical rulers, who were their dominant shareholders.

To give one example of how these super-companies were put to use, consider the Peruzzi company of Florence. As Joseph Farrell informs us, “the Peruzzi company began its rise to power by exploiting the situation between southern and northern Italy in the late 1200s and early 1300s. Namely, the Kingdom of Naples was, at that time, the grain supplier to the small city-states of northern Italy, and in return, was an importer of textiles and other manufactured goods from northern Italy and the rest of Europe … The Bardi and Peruzzi companies became the middlemen in this commodities trade, a fact that required the super-companies to have high capitalization.”

“As a result of this type of trade, the super-companies, much like their modern counterparts, became involved in all aspects of the trade, from production and manufacturing, shipping, and of course ultimately the issuance and exchange of currency itself.”

As Farrell then notes, the oligarchs behind this super-company leveraged the strategic positioning they had won for themselves over the trans-Italian trade market to win “special monopolistic concessions from the various governments in whose territories it was conducting business.”

Debt repayment owed to these bankers “was achieved mainly by diverting to the lenders certain revenues of the crown designated in the loan contracts, such as general tax receipts from a city, province, or the whole kingdom. … In other words, they negotiated a lien on certain revenues of the kingdom.”

“By 1316, the Peruzzi company had joined a consortium or syndicate of the other great Florentine companies to operate the mints of the kingdom of Naples, collect the taxes, and pay various bureaucrats and troops. In other words, the Florentine super-companies had essentially formed a cartel for the purposes of coordinating and controlling their activities in the Kingdom of Naples.”

“In short, they had negotiated away the sovereignty of the Kingdom of Naples. … Or, to put all these points more succinctly, they had acquired the sovereignty of the Kingdom of Naples by achieving control of essential state functions through the extension of loans and the imposition of what modern international banks call “conditionalities.”

Zooming out, Farrell catalogues the “playbook of techniques” utilized by the Italian oligarchs to gain economic and political control over Europe.

1) Retain familial control over the strategic operations of the company by maintaining controlling interest in the shares of its stock;

2) Penetrate or infiltrate the key institutions and operations of the state — diplomatic, governmental, and above all, the mints or currency issuance — by training family members and close associates in those fields, with the goal being to make government institutions and bureaucracies fronts for corporate activity;

3) Work within existing legal constraints — in this period, the Church prohibition against usury — by negotiating privileged positions for the company in trading rights, tax exemptions, and even tax-collecting;

4) Control, or at least influence, the entire range of the company’s activities, from shipping, to manufacture and production, to currency and commodity exchange affecting those operations;

5) Collateralize the infrastructure of nations themselves, particularly if that infrastructure is being constructed on the basis of loans made by the corporation;

6) Maintain careful posture of public neutrality in cases of political conflict, while continuing to act as financial agents for both sides.

35. Gold: A Vehicle of the Dharma

In its original iteration, money began as a credit-based accounting system organized by temple bureaucrats overseeing tax collection and the distribution of the king or emperor's resources preserved in the state storehouse.

Over time, as economies became more complex and international trade began to develop between cultures, economic oversight fell out of the hands of the temple and into private control.

Alongside this transition was a shift in the nature of money: it moved from a state-sponsored credit system to an oligarch-sponsored coinage system.

Here, money became physically rooted in the use of metal coinage, a resource that the bankers kept deliberately scarce and in demand.

Metal coinage was the key financial mechanism upon which the entire apparatus of the Greek and Roman empires were built.

With the collapse of these empires, and the subsequent rise of the Christian Church, this coinage was taken out of circulation, with international trade also collapsing as a result. Instead, local economies in Europe were returned to a priesthood-run credit system.

This remained the case until the fateful century of the 1500s, when the Renaissance and Reformation took root and the age of exploration started up in full force.

Both of these events were inspired in large part by the influence of the Italian oligarchs: the Renaissance being a project of the Medici dynasty of Florence and the age of exploration facilitated behind the scenes by the Venetians.

In addition to being behind these two major events, the Italian oligarchs were also behind a third: returning Europe to the gold standard previously implemented in Roman times.

As David Graeber explains, “the epoch that began with what we’re used to calling the ‘Age of Exploration’ … begins around 1450 with a turn away from virtual currencies and credit economies and back to gold and silver. The subsequent flow of bullion from the Americas sped the process immensely, sparking a ‘price revolution’ in Western Europe that turned traditional society upside-down.”

“What’s more, the return to bullion was accompanied by the return of a whole host of other conditions that, during the Middle Ages, had been largely suppressed or kept at bay: vast empires and professional armies, massive predatory warfare, untrammeled usury and debt peonage, materialist philosophies, and even the return of chattel slavery.”

Here, we find the familiar pattern of Rome’s capitalist oligarchy re-emerging, rising once again to stake its claim over the life of Europe.

But, as Graeber points out, “it was in no way a simple repeat performance. All the Axial Age pieces reappeared, but they came together in an entirely different way.”

One of the big new factors was that now the previously unreachable wealth of the Americas was brought into the fold: “Between 1520 and 1640, untold tons of gold and silver from Mexico and Peru were transported across the Atlantic and Pacific in Spanish treasure ships.”

In his book “Debt: the First 5,000 Years”, Graeber gives further details on how the resources of the Americas came into Europe to influence the course of its evolution, super-powering its oligarchs:

He writes that, upon their arrival in the Americas, “the Spanish and Portuguese empires stumbled into the greatest economic windfall in human history: entire continents full of unfathomable wealth, whose inhabitants, armed only with Stone Age weapons, began conveniently dying almost as soon as they arrived.”

“Their conquest of Mexico and Peru led to the discovery of enormous new sources of precious metal, and these were exploited ruthlessly and systematically, even to the point of largely exterminating the surrounding populations to extract as much precious metal as quickly as possible.”

Crucially, as Graeber emphasizes, none of this “would have been possible were it not for the practically unlimited Asian demand for precious metals.”

An endless desire for Middle Eastern and Asian commodities, possession of which served as important symbols of social status among its aristocratic elite, fueled the trans-Eurasian trade pipeline.

As Graeber elaborates: “Since Roman times, Europe had been exporting gold and silver to the East: the problem was that Europe had never produced much of anything that Asians wanted to buy, so it was forced to pay in specie for silks, spices, steel, and other imports.”

If the Asians hadn’t held a ceaseless desire for gold and silver, one that matched the Europeans’ unquenchable desire for their commodities, then the entire trans-Eurasian scheme wouldn’t have worked.

Clearly, there must have been some form of ancient coordination between the two to make this work. Was this originally established during Atlantean times? Was this older pattern resurrected in the new age by either the Aryan priesthood or, possibly, descendants of the former Atlantean Empire?

Graeber further explains that “the early years of European expansion were largely attempts to gain access either to Eastern luxuries or to new sources of gold and silver with which to pay for them.”

So while untold tons of gold and silver were flowing into Europe from the Americas through the Conquistadors, “very little of that gold and silver lingered very long in Europe. Most of the gold ended up in the temples in India, and the overwhelming majority of the silver bullion was ultimately shipped off to China. The latter is crucial. If we really want to understand the origins of the modern world economy, the place to start is not in Europe at all.” Rather, the real story is in Asia.

“By the late sixteenth century, China was importing almost fifty tons of silver a year, about 90 percent of its silver, and by the early seventeenth century, 116 tons, or over 97 percent. Huge amounts of silk, porcelain, and other Chinese products had to be exported to pay for it. Many of these Chinese products, in turn, ended up in the new cities of Central and South America.”

Graeber explains that, during the late Middle Ages, the trans-Eurasian bullion-for-commodities “trade became the single most significant factor in the emerging global economy, and those who ultimately controlled the financial levers - particularly Italian, Dutch, and German merchant bankers - became fantastically rich.”

The oligarchs who obtained wealth in this manner hoarded it for themselves, using it to further expand their power and prestige at the expense of the rest of society.

While they were re-engineering European society to once again become dependent upon gold and silver, “ almost none found their way into the pockets of ordinary Europeans. Instead, we hear constant complaints about the shortage of currency.”

“Despite the massive influx of metal from the Americas, most families were so low on cash that they were regularly reduced to melting down the family silver to pay their taxes. This was because taxes had to be paid in metal” - a situation the oligarchs strategically engineered into place to ensure demand among the populace for their product.

Stepping back, Graeber points out that “the new regime of bullion money could only be imposed through almost unparalleled violence - not only overseas, but at home as well.”

As a result of the new economic order the oligarchs put into place, the old pattern of insurrections that plagued Rome also re-emerged: “In much of Europe, the first reaction to the ‘price revolution’ and accompanying enclosures of common lands [lead to] thousands of one-time peasants fleeing or being forced out of their villages, ...a process that culminated in popular insurrections” of the same type that plagued Rome in the final stages of its decline.

As in Rome, “these rebellions were crushed.... Vagabonds were rounded up, exported to the colonies as indentured laborers, and drafted into colonial armies and navies - or, eventually, sent to work in factories at home. Almost all of this was carried out through a manipulation of debt.”

Summarizing the main themes involved with the capitalist oligarchy’s rise to supremacy in the West, Graeber concludes that:

“What we see at the dawn of modern capitalism is a gigantic financial apparatus of credit and debt that operates - in practical effect - to pump more and more labor out of just about everyone with whom it comes into contact, and as a result produces an endlessly expanding volume of material goods. It does so not just by moral compulsion, but above all by using moral compulsion to mobilize sheer physical force.”

“At every point, the familiar but peculiarly European entanglement of war and commerce reappears - often in startling new forms. The first stock markets in Holland and Britain were based mainly in trading shares of the East and West India companies, which were both military and trading ventures. For a century, one such private, profit-seeking corporation governed India.”

“The national debts of England, France, and the others were based in money borrowed not to dig canals and erect bridges, but to acquire the gunpowder needed to bombard cities and to construct the camps required for the holding of prisoners and the training of recruits. Almost all the bubbles of the eighteenth century involved some fantastic scheme to use the proceeds of colonial ventures to pay for European wars.”

The overall theme is that “debt money was war money, and this has always remained the case.”

These are the tactics of oligarchy: the “Shadow” of the democratic project the esoteric societies have secretly been working to establish over the course of millennia.

In order to achieve this grand ideal, we must first overcome its Shadow: the archetypal Adversary who always confronts the Hero in his quest for liberation and enlightenment.

For us today, as it was hundreds of years ago, this capitalist oligarchy still Shadows us: they are the Adversary that remains, confronting and challenging us to this day. Consequently, the challenge of overcoming this Shadow is the great task that remains for us to achieve before the philosophic ideal of World Democracy can be born and a new golden age commenced.

36. The Aztecs Meet Their Adversary (Part II)

Now that we’ve gone deeper into the geopolitical and economic backstory of the Spanish Conquistadors, we can better understand the larger institutional dynamics taking place within Europe which motivated their actions.

While the Spanish Conquistadors were outwardly motivated by a desire to spread Christianity to the “heathens” in the Americas, secretly, they were driven by the financial oligarchs of Venice, Florence, and Genoa, who utilized the incoming flow of bullion from the Americas to further expand and consolidate their power over the European crowns.

This provides the necessary context for understanding the actions of Cortes, who came to the Americas as an instrument of Europe’s banking oligarchs. Without the pressure of their debt-based financial system hanging over him, he never would have done what he did to the Aztecs.

Graeber writes that, “when dealing with conquistadors, we are speaking not just of simple greed, but greed raised to mythic proportions.... They never seemed to get enough. Even after the conquest of Tenochtitlan or Cuzco, and the acquisition of hitherto-unimaginable riches, the conquerors almost invariably re-grouped and started off in search of more treasure.”

Why? What were their motives? Delving into Cortes’ backstory, we find the answer: he and his fellow conquistadors were debtors seeking refuge from the rising tide of the interest payments that threatened to drown them.

Graeber tells the tale:

“Cortes had migrated to the colony of Hispaniola in 1504, dreaming of glory and adventure, but for the first decade and a half, his adventures had largely consisted of seducing other people’s wives. In 1518, however, he managed to finagle his way into being named commander of an expedition to establish a Spanish presence on the mainland.... He’d been living beyond his means, got himself into trouble, and decided, like a reckless gambler, to double down and go for broke. It is unsurprising, then, that when the governor at the last minute decided to cancel the expedition, Cortes ignored him and sailed for mainland with six hundred men, offering each an equal share in the expedition’s profits. On landing he burned his boats, effectively staking everything on victory.””

“Three years later, through some of the most ingenious, ruthless, brilliant, and utterly dishonorable behavior by a military leader ever recorded, Cortes had his victory. After eight months of grueling house-to-house warfare and the death of perhaps a hundred thousand Aztecs, Tenochtitlan, one of the greatest cities of the world, lay entirely destroyed.”

“After the imperial treasury was secured, the time had come for it to be divided in shares amongst surviving soldiers. Yet, ...the result among the men was outrage. The officers connived to sequester most of the gold, and when the final tally was announced, the troops learned that they would be receiving only fifty to eighty pesos each. What’s more, the better part of their shares was immediately seized again by the officers in their capacity as creditors - since Cortes had insisted that the men be billed for any replacement equipment and medical care they had received during the siege. Most found they had actually lost money on the deal.”

“These were the desperate men who ended up in control of the provinces and who established local administration, taxes, and labor regimes. Which makes it a little easier to understand the descriptions of Indians with their faces covered by names like so many counter-endorsed checks, or the mines surrounded by miles of rotting corpses. We are not dealing with a psychology of cold, calculating greed, but of a much more complicated mix of shame and righteous indignation, and of the frantic urgency of debts that would only compound and accumulate (these were, almost certainly, interest-baring loans), and outrage at the idea that, after all they had gone through, they should be held to owe anything to begin with.”

Cortes, the leader of this pillaging expedition, himself ended up indebted, with his possessions repossessed, eventually having to return broke to Spain.

Summarizing Cortes’s story, Graeber writes: “In classical Axial Age fashion, Cortes was attempting to use his conquests to acquire plunder, and slaves to work the mines, with which he could pay his soldiers and suppliers cash to embark on even further conquests. It was a tried-and-true formula.”

But for him and his fellow conquistadors, it proved a spectacular failure. This is always the case for everyone except the capitalist class - the holders of all wealth, who multiply it endlessly through the magic of compound interest.

As Graeber points out in the next paragraph, the rape of America and the sacking of Constantinople by the Crusaders followed a similar playbook. This makes sense, as both expeditions were planned and financed by a common oligarchical power structure.

He writes that, if the story of the Spanish Conquistadors “seems suspiciously reminiscent of the Fourth Crusade, with its indebted knights stripping whole foreign cities of their wealth and still somehow winding up only one step ahead of their creditors, there is a reason. The financial capital that backed these expeditions came from more or less the same place.”

Graeber also points out that, at key points along the pathway that lead to the extermination of the Aztecs and Inca, “those making the decisions did not feel they were in control anyway.” Instead, “financial exigencies ended up taking precedence. Charles V himself was even deeply in debt to the banking firms in Florence, Genoa, and Naples, and gold and silver from the Americas made up perhaps one-fifth of his total revenue.”

In the end, “Money always has the potential to become a moral imperative unto itself. Allow it to expand and it can quickly become a morality so imperative that all others seem frivolous in comparison.”

“For the debtor, the world is reduced to a collection of potential dangers, potential tools, and potential merchandise. Even human relations become a matter of cost-benefit calculation.”

This is the way the conquistadors viewed the worlds that they set out to conquer: from an impersonal, economically calculating perspective. This is the same perspective corporate managers have today.

As Graeber elaborates, “the structure of the corporation is a telling case in point - and it is no coincidence that the first major joint-stock corporations in the world were the English and Dutch East India companies, ones that pursued that very same combination of exploration, conquest, and extraction as did the conquistadors.”

Concluding his ruminations, Graeber states that “It is the peculiar feature of modern capitalism to create social arrangements that essentially force us to think this way. … It is a structure designed to eliminate all moral imperatives but profit.”

“The corporate executives who make decisions can argue - and regularly do - that, if it were their own money, of course they would not fire lifelong employees a week before retirement, or dump carcinogenic waste next to schools. Yet they are morally bound to ignore such considerations, because they are mere employees whose only responsibility is to provide the maximum return on investment for the company’s stockholders.”

This is the psychology of Tezcatlipoca. It is the psychology of the Shadow; the Adversary. It confronts us as a great initiatory test we must collectively face and overcome. And we can only accomplish this by first each confronting its roots within ourselves.

This oligarchical Adversary that confronts us externally feeds itself off the Shadow Complexes that we maintain within ourselves. In order to defeat the former, we must first address the latter, thereby cutting off the energy supply of this Adversary.

This is why philosophy is the desperate need of our world. We need the Philosophic Empire.

As I’ve argued throughout this book, philosophy is the institution divinely purposed to lead mankind past the confrontation with its Shadow and into the Light of Self-awakening that lies beyond.

In terms of civilization, this represents the coming of a Golden Age: a state of world enlightenment; the great dream of the ages, one that we all know in our hearts is possible. The Philosophic Empire is the only vehicle that can take us there; therefore, we must work together to realize this grand ideal as soon as possible.

It is only by coming together to resurrect the lost institution of Philosophy that we can gain the wisdom and strength necessary to collectively face and overcome the capitalist Shadow Complex that has plagued human psychology for millennia and still plagues us today, this Adversary being simply a personification of the illusions, fears, and blockages we continue to maintain within ourselves.