Francis Bacon, Godfather of the Scientific Age (1 of 6)

Part 1: The Politics of Early Christianity

Preface:

This article begins the sixth chapter in a ten chapter book project titled “Philosophy: Its Origin, Purpose, and Destiny”. The contents of this book are available to read for free on my Substack (www.thewisdomtradition.substack.com).

If you click on the “Publications” section on my website (www.alexsachon.com) you can find a table of contents for the book along with links to the first five chapters published so far.

In addition to my written material, I also host a podcast (called “The Wisdom Tradition”), where I review each of the articles and offer additional commentary on their main themes and arguments. Also featured are stand-alone episodes offering supplementary material which contain relevant information not contained in the written articles.

This current article is part one of a planned six-part series on Francis Bacon and the role he played, largely in secret, in establishing the institutional foundations of the modern world.

The focus of the first two articles in this series is to establish a comprehensive framework of European history from the time of the fall of the Roman Empire to the time of the English Renaissance, beginning in the late 16th and early 17th centuries AD.

This material serves to inform the content of the latter articles of this series, which will explore the legacy of Francis Bacon and the important activities he conducted on behalf of the Esoteric Schools during the early 17th century.

In this article, we focus on Europe’s transition out of the Roman Empire and into the age of Christianity. In the follow-up article (which will be part 2 of this series), we will progress the story, tracking how schools of esoteric philosophy perpetuated themselves in secret under the nose of the Church, which fiercely opposed them. Ultimately, these schools are responsible for the gradual transformation of Europe out of the Dark Ages and into the age of Science.

After this, stay tuned for the rest of this series; the various articles comprising it will be published sequentially and all go together to form the complete chapter.

We will now begin this article by picking up where we left off in our previous chapter on Plato: with the end of the Axial Age and the transformation of the oligarch-run pagan world order into a new paradigm, one characterized by competing feudal states ruled over by a new European hegemon: the Roman Catholic Church.

1. Europe’s Transition into Christianity

In our previous, six-part article series on Plato, we covered the rise and fall of the pre-Christian (i.e. “pagan”) civilizations. In that chapter, we began our analysis with the River Valley civilizations of ~4,000 BC before moving down to investigate the events of the Axial Age, which extended from roughly 600 BC to 600 AD.

At the end of this Age, during the 6th century AD, Roman emperor Justinian formally outlawed and forbade the existence of pagan religious practices, thereby crowning Christianity as the official religion of the West, a position it still upholds today.

By this point, the greatness of Europe’s old religious institutions - the Mysteries - had already fallen to a low point. In fact, they were almost extinct, as the hierophants and adepts of the old Mysteries “found few who were qualified to carry on the secret teachings and many of the masters died without a successor” (MPH).

Meanwhile, an insatiable appetite for the accumulation of wealth and power captured the imagination of the leadership classes of European and Mesopotamian Civilization, with empires dominated by war-profiteering oligarchs emerging to take control over the major civilization zones of the West.

In our previous series on Plato, we discussed the political and economic developments of the Axial Age in great detail. One of the factors we noted as being of crucial importance to the widespread emergence of oligarchy and empire during this period involved a transformation in the economic and financial affairs of society.

During this period, all across Eurasia, money shifted from a credit-based system run by the state to a precious metals-based coinage system run by private interests. This financial elite became the foundation of a powerful oligarchical class who would conspire take control of the state and its people in order to consolidate its rulership over the masses.

The money interests that took control over Axial Age civilizations like Greece and Rome were ones captivated by imperial ambitions. Their bread and butter was usury and war, with their money and power being derived from their connections to war-making, slavery, and wealth extraction.

Though the problems of oligarchy, empire, debt, and materiality became widespread in Eurasia throughout this period, Rome became their epicenter - the civilization most captured by these “shadow” elements.

As the Roman oligarchy wrested control of the state from the monarchs, they turned it into a perpetual war, slavery, and debt machine.

As this took place, a widespread mood of materiality, secularity, greed, and selfishness swept through the collective psyche of the empire, and civilization began breaking down as a consequence.

In his article “If Christ is Risen”, Manly Hall discusses the materialism of Rome in depth.

He notes that “from the beginning, Rome was concerned essentially with conquest, barter, and exchange.” In the course of its empire, it would spread these materialist values across Europe.

The world that Rome was initially born into was one that was “largely dedicated to religious concepts and the institutions through which such beliefs were disseminated.” But as the Roman Empire expanded and impressed its authority over the states and cultures of Europe, this began to change.

Gradually, through conquest and colonialism, Rome spread its materialist mindset by infecting the cultures of its various vassal states with it. It impressed upon the institutions of its colonies a value system that prioritized the glory of Rome over the glory of God.

Hall explains that “to the Roman mind, man lived while he lived; and in this living, (his duty was to) build the world and advance the political courses and fortunes of nations.”

In the worldview Rome mandated, “the Caesars were the personifications of gods, and the expansion of the empire under their leadership was the real purpose for human existence. Men lived to glorify the Roman way of life. … To labor for Rome was good citizenship; to pay the taxes was the law; and to die for Rome, was the highest valor.”

Overall, Rome’s policy wasn’t to overturn the local religions of its conquered vassals; rather, it was to corrupt them and infect them with its doctrine of secular materialism. “Men could worship as they pleased, so long as their faiths did not impel them to question the ideology of the State.”

This situation formed the immediate geopolitical context in which the new religion of Christianity initially emerged.

Although Rome sought to impress its materialistic, secular, and wealth-driven values upon the face of Europe and Mesopotamia, it was never completely successful at stomping out the religious and philosophical leadership of its vassal states. These spiritual leaders inspired rebellions against the empire.

On the periphery of the Roman Empire arose a continuous stream of rebellions against the extractive Roman oligarchy and the vapid culture of materialism they were implementing. In Mesopotamia, “the Jewish mystics were in open rebellion against the cult of emperor worship.” Meanwhile, “in Britain and France, the Druids were driven underground, but their influence was not entirely destroyed.”

The spiritual leaders of these groups and others realized that “there was only one way of breaking the power of Rome, and that was by assailing its weakest part - its inability to satisfy the inevitable instinct of man to require a concept of life after death.”

The Empire persisted upon a shallow and materialistic cult, one that was oriented around the worship of a false idol: the emperor and the Roman state.

Christianity spread as a social movement and counter-reaction to this situation: “around the concept of eternal life (Christ), the forces rallied that were to finally overthrow the proudest city ever built by mankind.”

Christianity emerges as a project of the leaders of various disenfranchised Mesopotamian and European Mystery Schools, ones whose peoples were being subjugated by the Roman state.

The spiritual leaders of these schools synthesized together their symbols and rituals, alongside those of ancient Egypt, Persia, and Asia, in order to found a new hybrid religion: Christianity.

This new religion was one custom-designed to hit the Roman Empire at its weakest points, thereby facilitating its overthrow.

The ambassadors of the Christian message came into the Roman territories and declared that the immortality of Christ was a great and glorious fact.

They argued that “if one man, even though he be divinely overshadowed, could come back from the darkness of the grave, could live as a conscious being after his body was dead, and by his own supreme achievement open the gates of everlastingness to all men, then materialism was vanquished.” (MPH)

By implication, man had an obligation to this immortal spiritual principle within themselves, one that superseded their obligation to the Roman state or its emperor. “Allegiance could no longer be first to Rome; rather, it belonged to the invisible universe from which men had come, and to which they would depart again.”

“Thus, there was a ruler greater than Caesar, a law higher than the Roman law, a reason for existence more noble than fighting and dying to expand the domains of Rome. Under the pressure of this psychology, the Roman Empire crumbled, until finally the Emperor himself had to bow before the concept of an eternal God. In that day, when Constantine acknowledged the growing power of Christianity, the proud city of the Caesars became itself the vassal of the Heavenly Power that rules all things.”

2. Christianity as a Social Reformation Project

When Christianity emerged onto the scene around the first century AD, it did so as a counter-reactionary force rising to move against the nihilistic, self-defeating mindset of the war-making Roman Empire, which had by that point extended its reach across most of central and western Eurasia.

Christianity arose as a counter-measure to the violence, decadence, and materialism of not just Rome but Axial Age empires in general. It emerged not only as a religion; it also represented a social movement that advocated a relatively simple set of moral and ethical values, ones that deliberately targeted the psychological vulnerabilities of the now-decadent pagan empires such as Rome.

In this way, Christianity sought to rebalance society away from the extremes experienced during the reign of the Axial Age empires. It emerged as a major factor in a grand project of breaking the cycle of oligarchical imperialism that had come to dominate the past several centuries of Eurasian history.

As history shows us, Christianity’s project to deconstruct the Roman Empire was a success. As economic historian David Graeber informs us that “the collapse of the ancient empires did not, for the most part, lead to the rise of new ones. Instead, once-subversive popular religious movements (like Christianity, Buddhism, and, later, Islam) were catapulted into the status of dominant institutions. Slavery declined or disappeared, as did the overall level of violence. … For most of the Earth’s inhabitants, (these developments) could only be seen as an extraordinary improvement over the terrors of the Axial Age.”

One of the key strategies that early Christian rebels emphasized in their effort to stamp out the power of the Roman oligarchs was to take away their main instrument of power: a debt-based, privatized financial system rooted in the use of metal coinage.

As we covered in our previous chapter on Plato, privatized finance rooted in the enforcement of a coin- and debt-based economic paradigm, one that the oligarchy controlled in every aspect, powered an insatiable military machine abroad. Domestically, the Roman war economy also had the effect of keeping the population at home in continuous debt, a condition which drove them into a state of perpetual dependency on the state.

With the onset of the Christian era, this instrument of power was taken away from the oligarchs. Economic and financial activity was taken out of private control and instead placed in the hands of the Church. As Graeber explains, “from the conduct of international trade to the organization of local markets, economic activity came to fall increasingly under the regulation of religious authorities. One result was a widespread movement to control, or even forbid, predatory lending (i.e. usury). Another was a return, across Eurasia, to various forms of virtual credit money.”

As part of their strategy to eliminate the old oligarchy-backed, coin-based economic paradigm, the Christian Church took the gold and silver that had previously been in circulation as money and parked it instead in their religious buildings and monuments. They replaced it with various credit instruments, which the Church (and later the Templars) maintained control of and oversight over.

In sum, the lasting political effect of Europe’s transition from the “pagan” age to the Christian era was that it broke the back of the oligarchs who had woven themselves into the fabric of pagan civilization.

Following the collapse of the Roman Empire and the rise of the Christian Church, the entire geopolitical landscape of Europe changed: instead of it being dominated by a few large oligarchical empires, Europe was now politically fragmented and “balkanized” into various small-scale, competing feudal kingdoms and monarchies.

But while the political landscape of western Eurasia become decentralized, its religion and culture became integrated and centralized to a degree never before achieved. The Roman Catholic Church emerged to take custodianship over the former Roman territories, serving as the cultural and political glue that would bind them all together.

The result was a much stabler social environment for the majority of the population, at least for a time. It was certainly a departure from the chaotic political and economic situation that had existed before.

It was largely due to the influence of Christianity that “conquest and acquisition for their own sake were no longer celebrated as the end of all political life.” (Graeber)

But there was a trade-off to this stability: when Christianity replaced the old order of pagan religious institutions, they also did away with the advanced systems of culture and philosophy that these ancient religious orders protected.

The cultural greatness of the great pre-Christian civilizations was derived from the accomplishments of a small philosophic elite.

While the initiates of these old civilizations accomplished much, the vast majority suffered in ignorance. With the move to Christianity, the plight of the majority improved, but the high culture created by this elite philosophic class became almost completely destroyed.

As a consequence of the deconstruction of the old cultural order, Graeber notes that “cities shriveled, and many were abandoned. But even this was something of a mixed blessing: certainly it had a terrible effect on literacy; but one must also bear in mind that ancient cities could only be maintained by extracting resources from the countryside.”

Put simply, the baby was thrown out with the bathwater: when Christianity renounced the entire older pattern of pagan civilization, they did away with a lot of evils, but in the same fell swoop they also renounced and separated themselves from the old wisdom tradition that the initiates of these older societies upheld.

As we will see, this separation of religion from its philosophical core would set the stage for the next 2,000 years of human history.

3. The Significance of the Christian Message

As we just explored, Christianity emerged as an important factor in the political and economic reformation of European civilization after the fall of the Roman Empire and the end of the materialistic excesses of the Axial Age.

Political and economic reform was not all that Christianity brought to the table, however: it also incorporated a number of significant innovations to the exoteric or public religious institutions of Eurasian civilization.

The innovations and new features that Christianity adopted brought certain key concepts and practices to the masses that had previously been emphasized only within the inner sects of the old Mystery Schools.

The most obvious of these new, previously-secret elements that Christianity brought out was the emphasis on the worship of the One God over that of the Many Gods of the pagan pantheons.

When we think of pagan civilization, we often think of their religious systems as being polytheistic, meaning they revered and worshipped a plurality of gods and divine agencies rather than one God, which is what the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) have come to emphasize in the modern era.

Within the ancient Mystery Schools, however, it was secretly taught that polytheism - the gods - existed always in relation to a superior, unified deity- the One God. Thus, the many gods of pagan theology were actually descriptive of the inner powers and agencies of one supreme God.

Thus, the One God was the true God of pagan civilization, but this truth was emphasized primarily to the initiates of these ancient civilizations rather than to their laypersons, who would not have knowledge of this theosophical “key” to their own religion.

First with the emergence of Judaism and later with the coming of Christianity and Islam, popular religions based on the doctrine of the One God came to replace all the older polytheistic systems.

In the case of the Christian faith, its aim became, as Manly Hall explains, to “build a Church with global dominion, dedicated to the One God.” No religious system of antiquity besides Judaism was backed by this type of spiritual mission.

This One God was the sovereign power before all life. It possessed a divine purpose or Plan, and it became the purpose of Christendom to bring this Plan into manifestation. Manly Hall elaborates: “Christianity, for the first time, enunciated to the public mind the doctrine that all creation and all created things indicate the unfoldment of a divine purpose through a series of collective incidents which must ultimately lead to the regeneration and perfection of creation.”

This sense of Divine Purpose was embraced with zeal by the Christian Church, who sent endless streams of missionaries out to the far corners of the Earth in order to bring this Plan into actualization. In the process, it consolidated its power over the hearts and minds of Europe, while ensuring the deconstruction of the old political and economic order of the Roman Empire in the process.

A second important innovation that the Christianity brought to European religion was an emphasis on a personal connection that each human soul has with God, one that manifests through God’s divine expression of “Love”.

In the exoteric or public understanding of pagan religion, the divine power of the gods was emphasized, respected, and feared, but was not “contacted” or personally connected with.

As a result, a distance was maintained between the commoner and the object of their religion. It was only in the inner, esoteric realms of ancient religion - the Mysteries - that the idea of contacting and building a relationship with God became revealed.

At this higher, philosophical level of ancient religious practice, the gods of myth were revealed as personifications of different aspects and powers of one’s own psyche. Here, at this inner, psychological level of religious interpretation, initiates leveraged the power of the gods in order to attain a transformative mystical experience, on where they become, as Manly Hall puts it, “immersed in the love and affection of the Divine.”

Thus, ancient religion was highly polarized: for the majority, God was distant and aloof; but in its inner, esoteric orders, an emphasis on the mystical Love of God brought deity up close and personal.

One of the effects of the lack of personal emotional connection with Deity that the majority suffered from was that few felt a sense of moral or ethical responsibility to do right by their fellow man.

The gods were conceived as moving mankind around the chessboard of life without mankind having much of a say; the most one could hope for is that these gods would look upon oneself and one’s family with favor. In the meantime, you took and conquered what you could.

It was this lack of moral and ethical backbone that contributed to the atrocities of the Axial Age and the Roman Empire; and it was this crisis of morals and ethics that Christianity stepped in and sought to immediately address. This they did by installing a relatively simple moral and ethical program upon the masses, one that emphasized piety over material aggrandizement, with the reward for good behavior being the eternal experience of God’s Love in the afterlife.

Christianity’s promise of God’s Love as a means of spiritual salvation appealed to large numbers of persons who had become traumatized from generations of atrocities and horrors that had befallen them and their families during the Axial Age.

The majority of the populace during this age was aware of only the exoteric or outer form of their religion, whose relative coldness brought them little consolation to deal with the ongoing series of crises and tragedies they were collectively experiencing.

It was into this situation that Christianity stepped, offering to the traumatized masses a new religious concept upon which the individual could build hope and faith, one which could sustain them under periods of crisis, pain, and suffering.

This new religious concept was built upon the revelation of God’s Love for man. This a salvational idea that had previously been emphasized only to the initiates of the Mystery Schools. Now, through Christianity, it was brought out to the masses, and the whole course of human history would be changed as a consequence.

4. The Mystery Schools Close Their Doors

The externalization of their once-secret philosophical teachings about “Divine Love” heralded a larger transformation taking place within the institutional structure of the old Mystery Schools.

The Mystery Schools existed at the heart of the ancient pagan religious order. From within the walls of their ancient temples, the priesthoods clothed their esoteric knowledge in the symbolism of myth and ritual.

Over the course of the Axial Age, as Eurasian civilization fell into an increasingly materialistic mode of being, the Mystery Schools ceased to wield the same level of influence over the rulers of the state that it once did.

Initially, their initiates worked in conjunction with the state monarchs in order to bring “enlightened governance” to society at large. But as the monarchs fell into corruption and were replaced by oligarchs who were equally corrupt, the “wise elders” of the Mystery Schools were no longer consulted.

At the same time, as oligarchy replaced monarchy and the collective psyche grew increasingly secular and materialistic in orientation, society-at-large stopped producing candidates capable of passing the demanding initiation rites of the Mystery Schools. As a result, many of the ancient masters died without passing their wisdom onto a successor.

The sages behind the ancient Mystery Schools foresaw the coming end of the age and made preparations to migrate their prized esoteric teachings over into a new institutional vehicle: philosophy.

The first philosophical schools, emerging at the beginning of the Axial Age (~600 BC), existed alongside the ancient Mysteries. The initial cohort of teachers who originated these schools were initiates of the Mystery Schools.

These initiates were sent out from these Mystery Schools as part of a deliberate project to seed the fundamentals of the esoteric worldview into the outer body of society. This was accomplished by establishing schools of philosophical instruction open to the public.

The first philosophic schools that emerged during the beginning of the Axial Age concealed the fact that a higher level of esoteric, mystical doctrines were taught to their most advanced students. This was a model they had brought over from the Mystery Schools.

After the fall of pagan civilization and the collapse of the old religious orders (~300 AD), this situation changed: there was a widespread movement within these philosophical schools to reform and restructure their body of teachings so that now the existence of an inner, mystical doctrine would be transparently revealed.

Thus, with the dying out of the old religious orders, the original philosophical schools were freed to more explicitly incorporate the esoteric and mystical aspects of ancient philosophy into their doctrines.

Here we find a connection between reformation movements taking place in both philosophy and religion during the closing years of the pagan era: in both cases, we find the Love aspect of Deity coming into prominent emphasis.

In the case of the movement of European civilization toward Christianity, the promise of an experience of God’s Love in the afterlife becomes the basis of a grand socioeconomic reform project, one that sought to replace the materialistic values of the previous age with spiritual ones.

At the same time, the incorporation of this doctrine of Love into the philosophical schools of antiquity also lead to transformative changes, one that involved a newfound emphasis upon mysticism. In terms of mysticism, Manly Hall explains that “Love is a catalyzing agent for the ego’s self-release. That which cannot be bridged by consciousness is bridged by complete self-forgetfulness in the service of that which the mystics call ‘the beloved’.”

One example of a philosophical school transformed by an injection of Cosmic Love comes with Platonism’s transformation into Neoplatonism. Alongside the Christian transition, we see arise in Alexandria a new, mystical order of Platonic thinkers. This new generation of Platonists emphasized mysticism and made important alternations to the older body of Platonic teachings in order that it may more directly express mystical and “theurgic” themes. In the new doctrine that resulted, the goal of the philosopher becomes to actually experience and intimately connect with the various metaphysical aspects of Plato’s system of teachings. This is accomplished by means of secret esoteric disciples and occult practices.

Another example of this shift comes with Buddhism: right around the same period that Neoplatonism emerges, we see Buddhism undergo a similar transformation. What had previously been a rather severe and ascetic doctrine of ethical and moral codes became enriched with an injection of highly mystical teachings and formulas. According to the new generation of Buddhists that emerged during this period, these mystical doctrines had always existed within the Buddhist schools but had previously been concealed from the awareness of all but the highest level of students and disciples.

It is notable that, within these philosophical schools, the emergence of an esoteric doctrine emphasizing the salvational nature of God’s Love comes at exactly the same time that Christianity is arising as a popular religious movement within the vestiges of the fallen Roman Empire - a movement which is also premised around a newfound emphasis on the transformative power of God’s Love.

Zooming out, the pattern becomes clear: with the decline of ancient civilization, the core aspects of the esoteric philosophical teachings of the old Mystery Schools becomes externalized.

The most important mystical elements of the teachings are moved into various philosophical schools, including Neoplatonism, Hermeticism, Gnosticism, Cabalism, Mahayana Buddhism, and others.

At the same time, key elements of its once-secret teachings are woven into the fabric of the emergent Christian religion. Philosophic historian Richard Tarnas elaborates on this transmigration of knowledge out from the Mysteries and into Christianity: “In the process of the Hellenistic world’s adoption of Christianity, many essential features of the pagan mystery religions now found successful expression in the Christian religion: the belief in a savior deity (i.e. a Hero God) whose death and rebirth brought immortality to man; themes of illumination and regeneration; ritual initiation with a community of worshippers into the salvational knowledge of cosmic truths; the observance of a preparatory period before initiation; demands for purity, fasting, vigils, etc.; … ritual processions; pilgrimages; the giving of new names to initiates (i.e. those ‘born again’),” etc.

Manly Hall highlights the main underlying theme behind this extraordinary motion of events: “the barriers to the Mysteries were broken open; access to certain types of information was no longer constrained as it had been. … The teachings once reserved for the few began to be consumed by the many.”

As the pagan empires declined, the once-concealed knowledge of the ancient Mystery Schools was ported over into various new institutional vehicles. Its most esoteric teachings moved over to the philosophical schools, transforming them in the process. Meanwhile, other key aspects of the Mystery teachings were brought out and seeded into public awareness through the vehicle of Christianity.

Once the externalization of the old wisdom teachings took place across these two paths of descent, the Mystery Schools formally closed their doors and the ancient religious orders that once protected them fully disappeared from public view. A new age had officially begun.

5. The Church Rejects Philosophy

As we explored above, when Christianity emerges, it does so as the centerpiece of two overlapping yet distinct projects:

a) On one hand, Christianity emerges as part of a political, economic, and sociocultural reform project targeted at maneuvering European and Mesopotamian civilization away from the materialistic extremes of the Axial Age.

As part of this project, Christianity was highly motivated to distance itself from all aspects of the previous political order it was seeking to replace, including not only its religious foundations but also its economic, cultural, and political institutions.

b) On the other hand, Christianity also emerged as a deliberate project of the ancient Mystery Schools to bring previously concealed aspects of their doctrine out into public view. Certain of their key philosophical teachings were embedded in the very fabric of the Christian faith. Here, they would be carried on into the new age that was to come.

As the Christian Church gradually consolidated and grew in power, a tension arose within itself between two conflicting truths:

a) Its need to market itself as being in total opposition to the pagan empires that came before; and

b) The reality of its connection to the religious philosophies and Mystery Schools of those same ancient pagan civilizations.

As history shows, the first factor - the Church’s desire to repudiate its own connection to the past - is the one that won out.

Manly Hall summarizes the Church’s point of view in making this decision to break all ties with the past. In their eyes, “there must be a complete separation of Christian and pagan interests. So long as it was obvious that the Christian sect was indebted to the pagans, it occupied a dependent position. Therefore, this indebtedess must be wiped away.”

Hall continues, noting that because Christianity was to be a religion different from paganism, the Church saw that it must “compete with and excel the pagan institutions” in order to assume spiritual leadership over the hearts and minds of man.

The Church’s strategic decision to completely renounce its connection with pagandom necessitated the requirement that it create a new mythology for itself, one that would pronounce its faith as a new and unique divine revelation to the world; “a complete system of revelation entirely separate and unique” (MPH).

In the Church’s view, it “must rise as a temporal institution and become the center of a Christian civilization.” For it to do this, all other competing faiths and traditions must go. Consequently, “with one imperious gesture it dissolved the body religious, consigning all the previous knowledge and beliefs of man into the limbo of decadent cults.”

As the self-appointed custodians and masters of a new Christian world order that was to come, the Church “clergy set itself apart as an eternal priesthood, which would bestow its favors only upon those entirely dedicated to Church purposes.”

Philosophic historian Richard Tarnas elaborates on the worldview that the Church came to advocate for itself:

“Unlike the mystery religions, (which existed and thrived within many different cultures and religions), Christianity proclaimed and recognized itself as the exclusively-authentic source of salvation, superseding all previous mysteries and religions, alone bestowing the true knowledge of the universe and a true basis for ethics. Such a claim was decisive in the triumph of Christianity in the late classical world.”

In the Church’s own view, they were uniquely "God’s representative on earth, a sacred institution whose continuing tradition would serve as the exclusive interpreter of God’s revelation to humanity.”

Thus, “with the rise of Christianity, the pluralism of Hellenistic culture, with its various intermingling philosophical schools and polytheistic religions, was replaced by an exclusive monotheism.” (Note: these quotes from Richard Tarnas are from his book Passion of the Western Mind.)

Manly Hall further elaborates on the unique brand of monotheism that the Church came to proselytize:

In the view of early Church fathers like Augustine, the Church was God’s uniquely chosen institution in the world. It was “the gift of Christ, the only begotten son of God, who through his miraculous birth, ministry, and death had given to the world his Church and sustained it by Apostolic Succession. Outside of the Church, none could find salvation; the door of the Church was the entrance to all hope.”

In their interpretation, “Jesus Christ is not the savior of the world but the savior of the church only, which is His particular sanctified institution, set apart and unique, infallible, unchangeable, and immovable. Even within the Church itself, Christ is the savior not of all the congregation but only of the elect, and this salvation is achieved under ecclesiastical conditions. There can be no variation.”

As the Church came to see it, “it is the Church, not Christ himself, who is the mediator between God and man. Thus the Church becomes the very mechanism of redemption, and there is no place in heaven for any outside of the Church. … Christ, the universal redeemer, disappears.” (MPH)

In the worldview mandated by the Church, “good and evil cease to be moral virtues and are instead determined solely by reference to invariable (scriptural) dogma.”

In order to position itself as the sole hegemon over the religious life of Europe and the Near East, Christianity became highly dogmatic in its adherence to biblical scripture over all other forms and traditions of knowledge.

On this, Richard Tarnas writes; “with the Church’s gradual emergence as the dominant structure and influence in the early Christian religion, the writings that now constitute the New Testament, added to the Hebrew Bible, were established as the canonical basis for the Christian tradition.” This canon of scriptural teachings "effectively determined the parameter of the evolving Christian world view.”

In other words, Christian concepts of reality and truth became confined to fixed and unchanging (i.e. canonized) traditions of interpretation concerning a small and highly selective set of biblical scriptures.

As Manly Hall further elaborates, “words became important - more important than ideas, and orthodoxy required an absolute and literal acceptance of words. Interpretation was not permissible, because it would inevitably incline the mind away from the literalness of words … When men began to think, their thoughts escaped the Christian boundaries.”

As a defense against such “wayward thinking”, the Church priesthood declared that “the Church and its dogmas are absolutely infallible and must be obeyed in all respects if the spiritual state of the soul is to be assured.” Consequently, they saw it as the Church’s duty “to enforce the acceptance of its dogmas, and if necessity arose, it was fully justified in using the military power of the State to compel obedience.”

This policy of “obey our dogma or else” put the Church at odds with the philosophical schools that had survived the downfall of the old empires.

In swearing its opposition to everything that came before, Christianity denied the validity of any source of knowledge beyond that of biblical scripture. As a consequence of this denial, it separated itself from its connection to the vital body of wisdom teachings possessed by the ancient philosophical schools.

In its zeal for world domination, the Church attacked not only all rival ancient religious orders but also the philosophical schools that they were connected to. They even attacked and eliminated the teachings of philosophical schools sympathetic to the Christian message, such as Gnosticism and Neoplatonism.

In the Church’s view, if a complete conversion of Europe to Christianity was to be ensured, only pre-approved orthodoxies could be allowed to survive. Consequently, all other faiths and competing interpretations of Christianity must be eliminated.

As Manly P. Hall explains, the early Church fathers understood that “the Church must become one structure within itself before it could hope to impress the power of this unity upon a doubting world…. Orthodoxy must be defined,” and everything outside of that orthodoxy must be eliminated.

Thus, the Church fathers realized that “in order to become a great religion the Church would have to stamp out the schismatic cults which had risen within itself, schisms which were due largely to streams of pagan thought flowing in through various bishops” within its own ranks who had originally “been born and educated as pagans.”

As we will see, this strategic policy of the Church to eliminate all competition would have large and profound consequences for the subsequent development of Eurasian civilization.

6. The Mystery Schools Go Underground

Manly Hall points to Gnosticism as a hallmark example of the Church’s persecution of an internal Christian sect who offered an alternative, non-orthodox interpretation of the Christian message.

Gnosticism emphasized a spiritual and mystical interpretation of the Christian faith, one that completely dismissed the claim of the Church hierarchy to be the exclusive custodian of man’s access to God.

Summarizing the situation, Hall writes: “Early in its history the Church waged a violent conflict with the great pagan systems of Philosophy and religion with which it was surrounded. As the power of the Church increased, it attacked these systems more and more openly. In some cases it was able to exterminate entirely the older cults and heretical groups. So perished the Gnostics of Egypt and Syria.”

Going into further detail, Hall explains that “Gnosticism was the great heresy of the ante-Nicene period of church history. The fathers of incipient Christianity, having elected themselves the custodians of salvation, exercised this prerogative to stamp out all traces of Christianity as a philosophical code.”

He explains that “Gnosticism was despised by the Church because it sought to interpret Christian mysticism in terms of the metaphysical systems of the Greeks, Egyptians, and Chaldeans” - the very cultures and civilizations Christianity was attempting to separate and distance itself from.

Consequently, “the church fathers considered the period of Gnosticism to be the most crucial in the history of Christianity, for at that time it had to be decided whether the new cult should be a religion or a philosophy. If the Gnostics had won, Christianity would have been regarded as the legitimate heir to the philosophic wisdom of preceding ages and would have gone forward as an interpretation of all the great systems and teachers that had preceded it. When the Church succeeded in dominating the situation, however, it was decreed that the new revelation should become a faith and retain its isolated infallibility so that its hand was against every unbeliever.”

What happened to the Gnostics was indicative of a larger pattern, one where the Church consistently persecuted and destroyed any heterodox sect who emerged to teach a more philosophical or mystical interpretation of the Christian message.

As a consequence of the persecution they faced at the hands of the Church, the philosophical schools and mystical orders of Europe and Mesopotamia were forced to move underground, perpetuating themselves through secret societies and front organizations of various forms and types.

Manly Hall summarizes the overall pattern: “Once Christianity had rejected paganism, it refused to recognize the Esoteric Orders of the pre-Christian world. It regarded them as detrimental to its own prestige, and sought relentlessly to exterminate them. This was impossible, but the Church refused to accept and to teach a universal religion or a universal philosophy.”

In truth, “the spiritual mysteries of life belong to no one faith, race, or school. But in order to advance itself as the supreme custodian of salvation, ecclesiasticism had to reject the Mystery System. In doing so, it did not destroy that system, but forfeited its own place as an instrument for the fulfillment of the Great Plan.” (Masonic Orders of Fraternity)

Consequently, this antagonistic attitude by the Church toward philosophy “marked not only the end of pagan era and the rise of dogmatic theology over philosophical reason, but also a transformation in the institution of the mystery schools, from being open to the public to being not only closed but eradicated from public consciousness.”

7. The Heresy of Manes

After the Gnostics, another sect of pagan philosophers turned Christian mystics emerged under the leadership of a figure named Manes during the 3rd century AD. The order founded by this Persian-born mystic would grow considerably in size and influence. Inevitably, the Church perceived it as a serious threat to its hegemony over western Eurasia.

As Manly Hall describes it, Manes’s approach was to “combine Christian theology and Asiatic mysticism. In many respects it paralleled Neo-Platonism. … Gradually, Manichaeism became the champion of the lost cause of pagan metaphysics (and became) a general depository of classical learning”.

“The followers of Manes called themselves the Sons of the Widow. They were the posthumous children of the ancient pagan world. Their temples had been destroyed, their mysteries profaned, their rituals perverted and their symbols misinterpreted, but still they endured, dedicated to the restoration of the Golden Age” when wisdom would be revived.

But after Justinian, one of the last emperors of the now-Christianized Roman Empire, “decreed the abolishment of all non-Christian sects, the Manichaeans were forced … to secrecy by the pressure of both State and Church.”

As a consequence of this powerful mobilization of forces against them, the Manichaeans and others like them were forced to take the sacred philosophical teachings and rituals they preserved underground: “Secrecy became their watchword.”

Here we find esoteric philosophy going “sub rosa” and a tradition of secret societies subversive to the aims of the Church coming into formation.

Hall elaborates: “Thus came into existence a secret empire of men bound together by an oath. … From the time of Manes to the present day, the Church has wrestled with an organized structure of heresy. It has attempted again and again to destroy this hidden empire, but although it has cut off branch after branch and cast it into the fire, the tree lives and sends out new green shoots from its hidden root.”

In his article “the Meistersingers of Nuremberg”, Manly Hall offers further insight into the what the Manichaeans believed and how they operated.

Hall informs us that “gradually the Manichaeans drew to themselves a powerful group of intellectuals who refused to accept theology’s effort to dominate the functions of the human mind.”

“In order to survive, the Manichaeans outwardly accepted orthodox Christian symbolism and used it to conceal their own doctrines. … Making use of symbols drawn from Christian theology, these mystics declared that Christ symbolized spiritual leadership (that comes from within), while the Church represented material leadership (imposed from without). Thus, in their thinking, Christ and the Church opposed one another - a view that caused consternation from the clergy.”

Going further into the differences between the aims of Christ and those of the Church, Hall notes that “the religion of Christ is Love, which has its seat in the heart. The religion of the church is Law, which had its seat in the church hierarchy. The church attempted to force conformity upon its members, and against this conformity the secret societies worked their stratagems.”

As the followers of Manes saw it, “the religion of Christ was the religion of love freely given without limit or boundary. Those who practiced the brotherhood of man, lived virtuous lives, and kept certain simple rites and sacraments, were the members of one invisible body - the Body of Christ.”

“This invisible body, the 'Secret Empire of the Good’, was the spiritual part of human civilization. This spiritual part struggled against the material ambitions of princes and priests who sought temporal supremacy in defiance of the words of Jesus Christ, that His Kingdom was not of this world.”

In time, various heterodox sects derived from the Manichaeans would emerge in the “shadows” of the Church’s vast religious empire. These hidden and secret societies would set up an invisible empire of their own, one dedicated towards a long-term spiritual mission: the establishment of the Plato’s Philosophic Empire on a global scale.

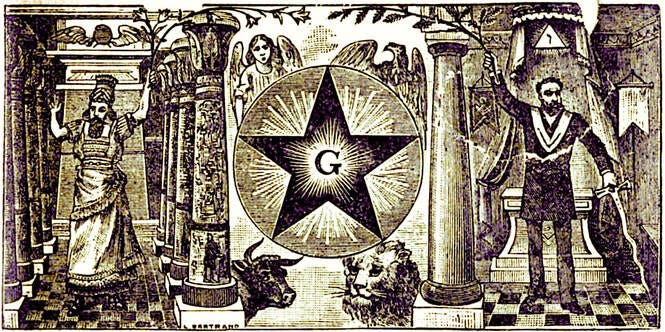

This grand philosophic mission passed gradually from the Gnostics and Manichaeans to the Templars and Albigensians of the Middle Ages. Then, from them it passed onward to the alchemists, troubadours, trade guilds, cabalists, Rosicrucians, Freemasons, Bavarian Illuminati, and others.

These groups were the ones responsible for instigating the cultural and scientific revolutions in Europe and the great political revolutions that were shortly to follow in America and France. As we will see, one figure - Francis Bacon - was at the heart of the activities of these later aspects of the Esoteric School’s grand project, which the Manichaeans and their descendants helped preserve during the long years of the Dark Ages.

8. The Essenes and the Jesus of History

The Gnostics, the Manichaeans, and other like-minded sects of esoteric philosophers saw the ambitions of the Church as being diametrically opposed to the actual teachings of Jesus.

Manly Hall summarizes the basic themes of Jesus’s teachings: “Christianity is best summed up in the commandments Jesus gave to his disciples: that they should love God wholeheartedly and their neighbor as themselves. The keynote is distinctly one of service to common need.”

As we explored above, the position of the Church came to be much different from this: its priests axiomatically declared that a literal interpretation of biblical scriptures was the only possible truth and that all other interpretations of the Christian faith as well as all other religions outside Christianity were heretical and in need of either conversion or extinction.

Manly Hall states that the Christian faith was originally intended to be a modified and reformed version of Judaism, one that would feature, like Judaism, a division of its religious philosophy into exoteric and esoteric branches, with the esoteric doctrine being for the initiates or “apostles” and the exoteric doctrine being for the layman and the public at large.

Hall describes Jesus as an Initiate of a small society of devout mystics called the Essenes, which populated the region of present-day Syria. This society was originally either founded or co-founded by the Greek initiate Pythagoras during the 6th century BC during the course of his many decades of travel.

The region had long-contained a Mystery School associated with the name “Melchizedek”, which Pythagoras had originally become an initiate of during his philosophic wanderings.

Pythagoras’s Essenian society integrated with this Mystery School, and it was here that the historical Jesus was initiated and brought into enlightenment.

Hall offers further detail on Essenian society and how it influenced the life and teachings of its initiate Jesus.

“It is generally supposed that the Essenes were … the initiators and educators of Jesus. If so, Jesus was undoubtedly initiated in the same temple of Melchizedek where Pythagoras had studied six centuries before.”

One of the chief objectives of this Essene community “was the reinterpretation of the Mosaic law according to certain secret spiritual keys preserved by them from the time of the founding of their order. It would thus follow that the Essenes were Qabbalists.”

“Joseph and Mary, the parents of Jesus, are believed to have been members of the Essene Order. Jesus was reared and educated by the Essenes and later initiated into the most profound of their Mysteries…. The silent years of His life no doubt were spent in familiarizing Himself with that secret teaching later to be communicated by Him to the world. Having consummated the ascetic practices of His order, He attained to the Christening. Having thus reunited Himself with His own spiritual source, He then went forth in the name of the One who has been crucified since before the worlds were (i.e. Christ) and, gathering about Him disciples and apostles, He instructed them in that secret teaching which had been lost - in part, at least - from the doctrines of Israel. His fate is unknown.”

Manly Hall also offers further elaboration on this secret “order of Melchizedek” that Jesus was a part of and ambassador for.

“In the New Testament, Jesus is called a ‘high priest after the order of Melchizedek’: The words ‘after the order’ make Jesus one of a line or order of which there must have been others of equal or even superior dignity.”

“If the ‘Melchizedeks’ were the divine or priestly rulers of the nations of the earth before the inauguration of the system of temporal rulers, then the statements attributed to St. Paul would indicate that Jesus either was one of these ‘philosophic elect’ or was attempting to reestablish their system of government.”

Hall also points out that Jesus, as an adept-initiate of the ancient Mysteries, was a man “twice-born”, meaning he was someone who had been enlightened and awakened to the light of God within.

“According to the old records, Jesus was an Essene adept versed in the mysteries of the Egyptians and of the secret societies of Syria and Lebanon.”

Like his fellow initiates within these orders, he was an awakened son of God. By implication other awakened souls besides Jesus also existed. Thus, Jesus was not the only son of God, as the Church claimed him to be. The fathers of the early Church knew this and recognized it without a problem.

As Hall explains ”the fathers of the early Church recognized a difference between Jesus and Christ. Jesus was the Nazarene adept, … (while) the Christos is the spirit of Universal Truth. Thus, to be ‘Christened’ means to be illumined or to have opened the inward faculties of realization.”

“Jesus the Christened, or Jesus the Christ, therefore means “Jesus the enlightened” or ‘the one upon whom the Spirit of Truth has descended’. There is a perfect parallel in the story of Buddha. The young prince of India was named Gautama Siddhartha. Under the Bodhi-tree he received the Illumination. The Spirit of Truth, “Buddhi”, which is universal wisdom, … was released out of his own nature. He then became Gautama Buddha - Gautama the Enlightened.”

According to Manly P. Hall, the death and resurrection of Jesus should be understood in this light: meaning, it should be understood as descriptive of the death-rebirth experience that the initiate goes through in their quest for spiritual enlightenment.

In philosophic terms, the Resurrection of Christ “is summed up in Plato’s doctrine that the body is the sepulcher of the soul…. By the Resurrection, therefore, we are to understand enlightenment ascending out of ignorance, the Truth within liberated to manifest through a dedicated and purified body. When man overcomes his appetites, masters his animal impulses, perfects and redeems his heart and mind from their addictions to destructive or illusionary concerns - this is the Resurrection.”

By implication: “The term Christian should be limited to one who (like Jesus) has received the inner light, and should therefore not be bestowed upon the congregation of any theological movement. A man is not a Christian until Christ is born in him.”

9. The Bible and the Jesus of Myth

If the above account of the real, historical Jesus’s life and teachings comes as a surprise, this is because the historical Jesus has been entirely wiped from the face of the Bible. There are two primary reasons for this:

First, the fathers of the early Church followed the example of the religions that had come before and transformed the historical life of their founder into a mythologized allegory. This is a pattern we find with earlier “pagan” heroes like Orpheus and Osiris; Christianity’s myth about Jesus follows the same logic.

Second, there was a division within the early Church among those who sought to utilize Christianity for political purposes and those, like the Gnostics and Manichaeans, who sought to use it as a vehicle to bring the ancient Mystery teachings into a new age. The first group won out, and began fitting together a version of scripture that is a partial and distorted selection from a larger body of teachings. The canonized scripture of the Church lacks internal cohesion, while also jumbling and making a mess of the esoteric symbolism that the philosophic wing of the faith was attempting to embed into it.

Let’s look at these two influences one by one, so as to unpack some of the deeper philosophical meaning of the Christian teachings.

In regards to the first topic, Manly Hall writes that “with the decline of paganism the initiated pagan hierophants transferred their base of operations to the new vehicle of primitive Christianity, adopting the symbols of the new cult to conceal those eternal verities which are her the priceless possession of the wise.”

One of their major efforts was to convert Jesus into a “hero god” resembling those celebrated in the old Mystery School initiation rites, such as Orpheus and Osiris. As Manly Hall writes, “The story of Jesus as now preserved is part of a secret initiatory ritualism belonging to the early Christian and pagan mysteries.”

This explains why, when undertaking a critical analysis of biblical symbolism, it is revealed that elements from the heroes celebrated in various ancient Mystery School traditions (such as Bacchus) “have been woven into the story of Jesus. The Eleusinian, Sabean, and Mithraic Mysteries are also evident, especially in the Apocalypse. Further, the Christian doctrine was certainly influenced by the Essenes, Nazarenes, and Therapeutic sects, now believed to have been of Grecian origin. The early fathers of the Church, in their interpretations of Christian mysticism, also drew heavily upon Gnostic lore of Syrian and Egyptian origin, and from the opinions of the Alexandrian schools” such as the Neoplatonists.

Thus, the Jesus of the Bible is a composite of pagan hero-gods such as Apollo, Osiris, Orpheus, Mithras, and Bacchus.

The archetypal “hero god” revered in the secret rituals of the ancient Mystery Schools was grounded in an esoteric interpretation of the Earth’s relationship to the Sun.

Mythologized hero gods such as Orpheus, Osiris, and Jesus are symbolic representations of the Solar principle: the transcendent divine power which the physical orb of the Sun personifies within the collective body of Nature.

Here, we come to understand that “Christ” actually represents “the solar power reverenced by every nation of antiquity. … If Jesus (the initiate) revealed the nature and purpose of this solar power under the name and personality of Christos, thereby giving to this abstract power the attributes of a god-man, He but followed a precedent set by all previous World-Teachers.”

Hall equates this esoteric interpretation of the Christ principle with the Jung’s idea that every human psyche is rooted within the consciousness of a single Universal Self. Hall explains that “mortal man achieves deification only through at-one-ment with this Divine Self.”

Jung based his entire concept of “individuation” upon the psyche’s grand quest to integrate with its own higher nature.

This principle of Self, the Christos principle, is the divine principle within every human. It therefore represents “man’s real hope of salvation - the living Mediator between abstract Deity and mortal humankind.”

The actual or “real” Jesus’ - the Jesus of history that was an initiate of the same esoteric order (Melchizedek) that Pythagoras previously had been - offered a version of these timeless wisdom teachings by giving the principle of Universal Self the name “Christ”.

Gautama Siddhartha, a counterpart of Jesus’s operating in the Eastern realms of the Eurasian continent, gave this principle of Universal Self the name “Buddha”. Either way, the same underling principle or concept is being indicated.

Hall explains that “Jesus disclosed to His disciples that the lower world is under the control of a great spiritual being (Christ; the Universal Self) which had fashioned it according to the will of the Eternal Father (a superior aspect of God which transcends Selfhood).”

In the language of Christian mysticism, “Since the Christos was this god-man (the Self) imprisoned in every creature, it was the first duty of the initiate to liberate, or ‘resurrect’, this Eternal One within himself. He who attained reunion with his Christos was consequently termed a Christian, or Christened, man.”

Of course, this is not the version of Jesus Christ that we find emphasized in the orthodox doctrines of the Christian Church.

Christian orthodoxy became crystallized around a partial selection of Christian scriptures drawn from a much larger body of early teachings. These became fitted into a pattern that halfhazardly followed certain ideas drawn from the Mystery Schools (such as their use of solar symbolism), but which rejected other aspects of their philosophical teachings. Instead, it replaced them with a doctrine of unphilosophical dogmas such as “vicarious atonement” which were unique to human history and at odds with the old Mystery School wisdom teachings.

The Jesus Christ of the Bible thus became transfigured into a distorted mythologized account; the actual teachings of the Jesus of history became subjugated and forgotten.

10. The Logia and the Lost Teachings of Jesus

In a classic article from the early 1940s titled “Christianity: Was It Originally a Philosophy or Religion”, Manly Hall states clearly and definitely that, “beyond question of a doubt, records concerning Jesus do exist. It is equally certain that they are now in the hands of people who do not intend to make them available.”

Why have they been kept secret? For the same reason as always: “they endanger the institution of Christian theology.”

In the records of esoteric philosophy, there once existed, in the early days of the Christian religion, a recorded account of the actual teachings of Jesus. These became known as the Logia, which translates as “the Words”, “the Speeches”, or “the Statements”.

Hall explains that the Logia represents “the oldest records we have concerning the teachings of Jesus to his intimates, disciples, and apostles.”

This mysterious body of records is referenced in the writings of the early Fathers of Christianity, where we find statements such as ‘It was written in the Logia…” or “the Master said…”

Hall expands on this, writing that the Gospels in the Bible were written not by the actual apostles they are ascribed to but rather by group authorship: “by people who had access to the early traditions, the Logia. They built the Gospel stories from this common source.”

In this way, the Logia’s existence is ephemeral: “they are known to have exited because they are cited in older documents, but they have disappeared over time and written versions of them, if any exist, have never been made public.”

Hall indicates that the Logia may have originally existed as an oral tradition; this may explain why no written records have survived. “It is quite possible that the Logia was never committed to writing, that it was memorized, and in substance became a book in the mind rather than on paper.”

Hall speculates that “these mental records, which for a time were passed on, with the death of the legitimate descent then vanished.”

While Hall indicates that no records of the Logia remain, he then goes on to give highly valuable details about what the contents of the Logia once contained. How he is able to do this, I will leave it up to the reader to speculate.

Manly Hall state that “the Logia, according to surviving fragments, is divisible into three general parts. One part consists of the words attributed to Jesus himself; the second part, those attributed to the Disciples, Apostles, and intimates; third, an account of the historical incidents and circumstances in the life of Jesus and his disciples.”

He continues: “The Logia itself, where it teaches the actual words and thoughts of Jesus Christ, his intimates, and his disciples, contains evidence of very important philosophic theories.”

Concerning the philosophical content of Jesus’s original teachings, Hall emphasizes that he “definitely teaches … the mystical imminence of God.” Meaning: “the mystical participation of Deity in all the circumstance of human life.”

If Deity is incarnate in all life and not just in the hierarchy of the Church, then the legitimacy of a world order controlled by the Church becomes fatally compromised.

While this teaching is inconvenient for Church orthodoxy, Manly Hall insists that it’s true. He writes that, according to Jesus, “Deity is not separate from its world, but is immersed in it. Deity functions through the world and is the source of all life that flourishes everywhere in Space.”

Hall also points out that, in the Logia, it is recorded that Jesus reverenced the principle of Christ as a universal one, one that belongs to all mankind and not just himself.

Hall writes that, “according to the continuation of the statement in the Logia, when Jesus refers to himself as ‘one with the Father’, he is not designating himself a unique person. He is merely restating that which is true of all people and all creatures.”

In the mystical thinking of Jesus, the Essenian initiate, we participate in God by discovering God within ourselves.

This union between ourselves and God has always existed. “What we call enlightenment or illumination is merely our discovery by conscious effort of Truths that eternally are. … We discover that we are truly living in God; that God is not in his heaven, but in us. As in everything.”

In this light, the Logia also contains enlightened teachings about the objectives of prayer.

Hall writes that “from the Logia we learn that in ancient times prayer was a form of meditation.”

Prayer, according to the Logia, is achieved by entering into the Self; by retiring from the objective into the subjective.” In this conception, “the individual, entering into a state of meditation or prayer, becomes aware of his eternal participation in divine matters.” This withdrawal into meditation means entering into the Father’s house, whose location is in the heart.

In sum, “in the Logia, the trend is toward individual communion with Truth and away from formalized dogma.” It ultimately advocates against the power of temporal religious institutions and instead emphasizes an “individual religious life.” As we have seen, this is a doctrine of teachings that was anathema to the political ambitions of a rising Church.

11. The Political Ambitions of the Church

A major part of the Christian Church's success in rapidly taking control of European civilization was that it was able to proselytize a custom-formulated theology specially designed to amass widespread popular support among the despondent masses living within the territories of the failing Roman Empire, which was locked in a gradual but inevitable process of deconstruction.

In his book Passion of the Western Mind, Richard Tarnas writes at length about the Church’s indebtedness to the social institutions previously erected and spread by the Roman Empire, which had come before and laid the foundations for the world order that the Church would later inherit and reorganize.

Tarnas writes that “a universal Christian religion of world proportions was made feasible by the prior existence of the Alexandrian and Roman empires, without which the lands and peoples surrounding the Mediterranean would still have been divided into an enormous multiplicity of separate ethnic cultures with widely diverging linguistic, political, and cosmological predispositions.” Thus, “the character and aspirations of the new religion were decisively molded by its Greco-Roman context.”

Writing on how the Church emerged as a product of its influences, Tarnas notes that “the established cultural patterns and structures of both the Roman state and the Judaic religion - psychological, organizational, doctrinal - were particularly suited to the development of a strong and self-conscious institutional entity capable of guiding the faithful and enduring through time” - this entity being, of course, the Roman Catholic Church.

In the case of its Judaic influence, Tarnas notes that the older Jewish tradition encouraged the Church to embrace “a powerful central hierarchy, a complex judicial structure governing ethics and spirituality, the binding spiritual authority of priests and bishops, the demand for obedience from Church members and its effective enforcement, formalized rituals and institutionalized sacraments, a strenuous defense against any divergence from authorized dogma, a centrifugal and militant expansiveness aimed at converting and civilizing the barbarians, and so forth.”

Tarnas also points out the impact that Roman influences had on the Church. These include “legislative battles, power politics, imperial edicts, military enforcement, and eventually assertions of divinely infallible authority by the new Roman sovereign, the pope.”

Like the emperors of Rome, the pope and the church hierarchy he oversaw wielded absolute authority, which “was declared to be God-ordained and unquestionable. He was the living representative of God’s authority on earth, a ruler and judge whose decisions regarding sin, heresy, ex-communication, and other vital religious matters were considered binding in heaven.”

Tarnas pinpoints the key dynamic taking place: “as the Roman Empire became Christian, Christianity became Roman.” In so doing, it inherited custodianship over the political order that the Roman Empire had originally established by war and conquest.

He explains that “after the (Roman Empire’s) division into an eastern and western sector, and after the western empire’s collapse in the wake of the barbarian migrations, a political and cultural vacuum occurred in much of Europe. The Church became the only institution capable of sustaining some semblance of social order and civilized culture in the West, and the bishop of Rome, as the traditional spiritual head of the imperial metropolis, gradually absorbed many of the distinctions and roles previously possessed by the Roman emperor.”

A transition of power took place, with “the Church’s boundaries now coinciding with those of the Roman state” The Church then became “allied with the state in maintaining public order and ruling the activities and beliefs of its citizenry.”

“The Church took over a variety of governmental functions and became the sole patron of knowledge and the arts, its clergy became the West’s sole literate class, and the pope became the supreme sacred authority, who could anoint or excommunicate emperors and kings.”

In short, the Church, intoxicated by power, developed an “ideal self-image” as “that of a spiritual Pax Romana reigning over the world under the guidance of a wise and beneficent priestly hierarchy.” In this way, “the fluid and communal forms of the primitive Church gave way to the definitively hierarchical institution of the Roman Catholic Church.”

The orthodox or exoteric Christian doctrine - the one presented to the public and institutionalized within their everyday social life - was one that imposed a rigid social hierarchy over a vulnerable populace by appealing to certain psychological sensitivities that had developed within that collective psyche - ones that had developed as a result of the centuries of mass atrocities that took place over the course of the rise and fall of Axial Age empires.

The Christian faith gained wide appeal and a rapid and loyal following because it offered the public certain salvational promises that had never been offered to it before. Unlike the ancient Mystery Schools, the asking price the Church was offering for access to this salvation was low.

As Manly Hall explains, “the integrity of the individual was the keystone of pagan idealistic philosophy. The unfoldment of the triune nature of man - spiritual, mental, and physical - was based upon the foundation of personal integrity.” But whereas the pagan Mysteries “declared the superior worlds to be attainable only by men and women of outstanding intellect and lives consecrated to individual regeneration, the criers of the Christian Church offered heaven with its eternal bliss to anyone who would confess his sins and affirm the divinity of Jesus Christ” and of the Roman Catholic Church, Christ’s chosen institution here on Earth.

Hall decries the situation that has resulted, writing: “these unnatural attitudes of theologians toward life have resulted in the establishment of an unnatural faith wherein the lofty principles of the ancient philosophers have been distorted out of all semblance to their true import.”

12. Vicarious Atonement and the Psychology of Debt

The specific instrument that the Roman Catholic Church and its offshoots utilized in capturing the hearts and minds of western Eurasia was their doctrine of “vicarious atonement”.

In its effort to capture the spiritual hopes of the Roman Empire’s former subjects, tributes, and slaves, the Christian Church introduced what Manly Hall calls “the most indefensible and at the same time the most vicious of all superstitions, namely, the doctrine of vicarious atonement - the redemption of a sinful world by the supreme sacrifice of one man.”

Hall explains that “while the myth of the dying god is to be found in many religious systems, Christianity was the first and only cult to construe the mythical incident as a literal atonement.”

With vicarious atonement, the Church adopted a distorted account of the old death/resurrection myth of the Mysteries. In their new version of the myth, “Christ becomes, so to speak, a scapegoat, the sacrifice offered up that the people might go free.”

“According to the church, the Passion abolished the old order of approach to Divinity and supplanted it with a brand-new modus operandi of salvation. Heaven, earth, and hell were all dislodged from their time-honored foundation lines, and the sins of all creation were wiped out by the blood of the Lamb.”

Historian Joseph P. Farrell highlights how the Church’s interpretation of Christ’s sacrifice fits into certain themes about money and debt - ones which, after the rise and fall of the capitalist empires of the previous age, were certainly at the forefront of the public mind.

Farrell writes that, according to the Church’s teachings, “mankind, by sinning, created an ‘infinite debt’ to an ‘infinite God’ who was angered by this debt and consequently condemned man to infinite and eternal punishment as a kind of ‘spiritual interest’” on this debt.

“Mankind, a finite creature, could never pay off” the principle on this debt “and hence, God (the Son) had to become man (which owed the debt) and be cruelly tortured and executed in order to pay off the principle of the debt.”

Thus, to believers of the Church, Christ came to represent a type of “debt jubilee” or “debt cancellation” for the Soul. To a population that had just come off being financially indebted to the usurious oligarchs of Rome, this was a highly attractive message.

In the Church’s telling of this tale, Jesus Christ only paid your debt if you swore fealty to its papal hierarchy and the dogmas it mandated; everyone else was left to suffer the consequences of God’s wrath.

The desired effect of this doctrine was to ensure, in the eyes of the public, that the Church would be accepted as God’s unique institution in the world: the sole gatekeeper between eternal damnation (staying in debt) or the salvation of one’s soul (the cancellation of one’s debt).

As a consequence of this doctrine of vicarious atonement, all that was required of the sinner was a “mere admission of the universal import of Christ’s incarnation and death”; this “became the sole prerequisite of spiritual redemption.” (MPH)

In practice, attaining this salvation required joining the Church. This meant admitting the infallibility of the Church hierarchy and pleading absolute fealty to its dictates.

The psychological desire to outsource one’s own salvation to an authority figure was a deep-rooted one that the Church hierarchy leveraged in its quest for temporal domination of Eurasia.

As Manly Hall explains, the Church’s message gained such wide popular appeal because the masses were not yet ready for something more demanding. The average person of the time “believed in the virtue of form and ceremony, and accepted their priests as intermediaries between themselves and God…. So long as men desired to worship heroes and pay homage to other men because of their titles, honors, and positions, the philosophic viewpoint was not applicable to their needs.”

The Christianity of the Middle Ages “was peculiarly suited to the needs of those who desired comfort and religious solace and at the same time did not want to burden their minds with the abstract formulas which only philosophers and mathematicians could understand.”

For this reason, the philosophical schools, which required greatness of their disciples, lost out, while the Christian Church with their orthodoxies won control of Europe. The dogmatism of orthodox Christianity “had a popular appeal because it in no way required a greatness of intellect. It was a religion of the masses and by weight of number, it achieved control of the political machinery of its time.”

In sum, Christianity emerges as a major innovation to the religious institutions of the Western World. At the same time, it also emerges as a major political project, one with aspirations of displacing the falling Roman Empire and re-engineering it into a Church-led Christian empire ruling over a political and economically neutralized tapestry of feudal European states.

A major consequence of Christianity’s political ambitions was that, to achieve victory, it was forced to sever its connection with the philosophical schools of the past. These became a mortal threat to its hegemony, since the Church was able to justify its absolute rulership over the medieval mind only by insisting upon a highly dogmatic and self-serving interpretation of Christian scripture.

Any thinking outside of the boundaries of its own pre-approved orthodoxy was a threat to its continued reign. This made the philosophical schools of the era its mortal enemy: the Church could only ensure its survival by suppressing and stamping out all competing claims to truth.

This dynamic sets up the next 2000 or so years of political intrigue, as these philosophical schools refused to die out. Instead, they moved underground, working through a machinery of secret orders, fraternal societies, guild networks, and front organizations.

Slowly but steadily, these secret societies worked toward the reformation of European civilization out from the Dark Ages and toward the ideal of an enlightened philosophic democracy - the Philosophic Empire of Plato.

In the late 16th century, Francis Bacon emerges as an important figure in the unfolding quest of these secret societies to achieve World Enlightenment.

In the next episode in this series (Part 2), we will introduce this important luminary and the secret society that he would become the spiritual and intellectual master over: the Rosicrucian Brotherhood.

Stay tuned for Part 2.

My Guy! Dude, I've been trying to read this article for a while now, but I just finished reading it and was blown away. Thanks for this information and man, thanks for exposing a new reality man!

Book me up to be a founding member - I would love to support this work!