Francis Bacon, Godfather of the Scientific Age (2 of 6)

Part 2: From the Templars to the Rosicrucians

13. Islam and the Preservation of Knowledge

In the previous article of this series (part 1), we discussed how, through use of populist doctrines such as “vicarious atonement”, Christianity was able to gain widespread public support across Europe. The Roman Catholic Church leveraged this social movement in order to wrest control of the political and economic infrastructure of the failing Roman Empire, taking it away from the tyrannical oligarchs who had previously controlled it.

The Church’s concept of Christian spirituality came to be defined according to a dogmatic orthodoxy, which it mandated as a means to place itself as the unique custodian over man’s religious life. As God’s uniquely chosen institution on Earth, the Church hierarchy placed itself in a position of near-absolute power over its subjects.

Under the influence of the Church, the psychology of Europe and Mesopotamia was steered away from the materialism of the Roman Empire and redirected inward, toward the religious life - an arena that the Church held complete control over.

In reaction to the material excesses of the previous Age, the Roman Catholic Church came to preach a doctrine of spirituality that entirely de-emphasized material existence.

As Manly Hall explains, this attitude “was the natural outgrowth of, and became most powerful in, an age of physical insecurity where life and property were in constant jeopardy. Investment in things physical had slight appeal where an entire community might be swept away to gratify a besotted emperor’s whim, or where tens of thousands might perish to furnish sport for a Roman holiday. … Where social inequity thus decreed unhesitating obedience to the dictates of tyrants, there inevitably resulted a philosophy which emphasized as the only conceivable freedom the state beyond the grave.”

In essence, the medieval Church concluded that one’s concern with material existence must be cast aside. Instead, the sole emphasis of life was placed on the effort of living a simple, devout, pious, Church-defined Christian way of life. It was only in this way that one’s soul could avoid eternal damnation and receive the promised award of a blessed afterlife state in heaven.

Of course, what constituted a pious Christian way of life was entirely up to the Church hierarchy to decide. Often, it meant persecuting, killing, and torturing the Church’s competitors and enemies - actions that hardly seem to align with the teachings of Jesus.

As a consequence of this anti-materialist motion within the Western psyche, Europe withdrew into an introverted phase of existence. As a result, it relinquished control of its economic and material life, giving custodianship of it over to the Church for safe keeping.

In order for the Church to maintain this privileged position for itself, it needed to forcefully mandate its religious system over the masses. The more the population felt a sense of spiritual dependency on the Church, the more control the Church hierarchy had over the economic, political, and cultural institutions of European society.

Thus, the Church, in order to maintain its hegemonic position over European affairs, was forced to mandate a highly dogmatic theocratic orthodoxy over the populace. This orthodoxy was a highly self-serving one, because it justified the unique position of absolute power that the Church was seeking to obtain over the body politic of Western civilization.

As an inevitable consequence of its policies, the Church made enemies of not only all other religions outside of itself but also of alternative Christian sects pursuing different interpretations of the Christian faith.

These heterodox Christian groups included among their number certain philosophical and esoteric schools who were attempting to synthesize Christian symbolism with the mystical doctrines of the ancient pagan Mystery Schools.

All such schools fell under extreme persecution by the Church and were forced to either disband or go underground, maintaining and perpetuating their heterodox doctrines in secret.

The problem for European civilization was that these esoteric schools were the custodians of the vital scientific and cultural systems of knowledge that made ancient civilization great. The end result of destroying this knowledge base was that Europe fell into a pitiful state of existence corresponding to what we now call the Dark Ages.

Manly Hall summarizes the essential dynamic involved: “for several hundred years European consciousness had introverted to an alarming degree. Completely isolated from contact with the learning of the past and with strong barriers of prejudice against non-Christian scholarship, the Europeans languished for lack of intellectual challenge.”

Due to this unfortunate situation in Europe, it became the prerogative of Christianity’s neighbor to the East - the rising Islamic religion, emerging within the former territories of the Persian Empire - to preserve the scientific and philosophical heritage of antiquity.

Islam is a faith founded in the 6th century AD by the prophet Mohammed. Mohammed was a merchant who, since his youth, had travelled along the caravan routes of central Eurasia. On these routes, he learned of the ancient wisdom tradition that had once flourished across Persia. He also met with Nestorian Christians, who informed of the origins and key doctrines of the Christian faith.

Disillusioned with the superstition and ignorance of not only his own Middle Eastern culture but also its Christianized neighbors next door in Europe, Mohammed made it his mission to bring about the reformation and restoration of religion, returning it to something resembling its primordial form of practice.

As Manly Hall describes, “Year after year Mohammed climbed the rocky and desolate slopes of Mount Hira and here in his loneliness cried out to God to reveal anew the pure religion of Adam, that spiritual doctrine lost to mankind through the dissensions of religious factions. … At last one night in his fortieth year, as he lay upon the floor of the cavern enveloped in his cloak, a great light burst upon him. Overcome with a sense of perfect peace and understanding in the blessedness of the celestial presence, he lost consciousness. When he came to himself again, the Angel Gabriel stood before him, exhibiting a silken shawl with mysterious characters traced upon it. From the characters Mohammed gained the basic doctrines later embodied in the Koran.”

As its origin story indicates, the Islamic religion sees Mohammed as a prophet - i.e. as a chosen instrument of God’s spiritual hierarchy. This is the same way the Muslims perceive Jesus - as a prophet, but not as the unique incarnation of God.

In this way, Islam emerged originally as something of a heterodox branch of Christianity, one that affirms many of the basic principles that Jesus Christ taught, but which denies the Church’s interpretation of how Jesus integrates with a larger concept of spiritual truth.

For this reason, the followers of Mohammed came to see the scriptural doctrines of the Roman Catholic Church as blasphemous, idolatrous, and corrupt. While they agreed with core elements of Christianity’s monotheistic interpretation of God, they insisted, like the Jews, that prophets such as Jesus are not direct incarnations of God but rather are merely messengers.

Islam differentiated itself from Christianity in another important way: while the Christian Church de-emphasized learning by labeling any form of knowledge outside of biblical scripture “heretical”, the Islamic faith did not share this attitude. Consequently, while the Church was busy subjugating and destroying ancient systems of knowledge in Europe, Islam rose to become the primary depository and protector of this wisdom for much of the Middle Ages.

The most outstanding example of the Islamic world’s embrace of knowledge and learning during the Middle Ages was demonstrated with the Moors of Spain. As Hall writes, “For nearly eight centuries under her Mohammedan rulers, Spain set to all Europe a shining example of a civilized and enlightened state. Art, literature, and science prospered as they then prospered nowhere else in Europe. Students flocked from France, Germany, and England to drink from the foundations of learning which flowed only in the cities of the Moors…. (In this era,) mathematics, astronomy, botany, history, philosophy, and jurisprudence were to be mastered in Spain and in Spain alone.”

For this reason, Hall reminds us that “we must never forget that the Dark Ages in Christian Europe were the bright ones of the Islamic world.”

14. The Crusades and the Templars

As Islam rose and prospered on its borders - to the West in Spain with the Moors and to the East in Mesopotamia and Persia - Europe was forced to “take stock of itself”. In this way, Islam served as a powerful reforming and censoring force upon the Church and the various feudal vassal states it held near absolute control over.

Islam confronted Europe as an external disciplining force: an “alien race” which made Christendom take stock of itself. This means that, due to the outside threat of Islam, Europe could no longer indulge in cultural and intellectual suicide without making itself vulnerable to being conquered and taken over by an invasion from the East.

As a consequence of this stimulation, Europe was forced to incrementally move itself out of the Dark Ages. The Church, monarchs, and feudal lords of the time were reluctant to make this change, but gradually, in large part due to the threat of Islam, they realized they had no choice but to accept at least some measure of progress.

The primary catalyst for Europe’s re-awakening came through the Crusades, which were four ill-conceived and ill-executed invasion attempts by Christendom against the Islamic world. These Crusades drew nobles and commoners alike from all parts of Europe, bringing them together to form a disunited, squabbling military force.

This force was directed into a disastrous confrontation with the “infidels” and “barbarians” to the East. Most who left for these Crusades did not return, and those who did discovered that the Islamic culture they encountered was not at all primitive and barbaric as they had originally assumed. Instead, the civilization they found was in many ways far in advance of the contemporary state of medieval Europe.

Manly Hall elaborates on the consequences that this “clash of civilizations” had on the psyche of European civilization: “When the Crusaders returned to their European lands, they brought back with them a perspective that was to change the whole course of human history. They had left Europe provincially-minded men with no knowledge of any culture other than their own. Dominated by the immense ecclesiastical pressure which held the whole world in thrall through what we call the Dark Ages, these Crusaders, when they reached the Near East, came in direct contact with a greater system of world culture: that of Arabia, the great Saracenic Empire,” whose culture, at the time, far eclipsed that of Europe.

Through contact with the Arabs, the Crusaders learned of the existence of a lost legacy of Egyptian and Greek philosophical thought, which originally had been brought over to Arabia in previous centuries in order that it might escape the persecution of the early Roman Church.

The Crusades represented an organized military effort on the part of the Church to ”liberate the Holy Lands (Jerusalem) from the infidels or non-believers”.

A military campaign such as this requires planning, funding, finance, arms manufacture, strategic management, tactical organization, transportation of goods and troops, etc.

In the age of great empires that preceded the rise of the Christian Church, when church and state were united, these functions would have been provided by either private mercenary armies or the state military force.

But when the Roman Empire collapsed and the Church took over political leadership of Europe, they did so in a form that separated Church and state. The Church maintained its headquarters in Rome, and from this location it ruled over the various feudal kingdoms of Europe. But as an autonomous institutional entity, the Church itself didn’t have its own standing army. Instead, they had to rely on their vassal principalities to provide this force.

Because of this dependency, the Church’s power over Europe’s feudal states was not absolute; the local feudal lords, nobles and monarchs of medieval Europe possessed at least some measure of political and economic autonomy from the Church.

While many of these feudal states and kingdoms were in constant war with each other, each could be called on, at moments of emergency, to offer soldiers and resources to the Church in order to fund its grand military initiatives.

In the case of the Crusades, we find four examples of instances where the Church commanded holy war against the Islamic world. In each case, nobles and commoners alike from around Europe were drawn together to answer the call.

The Church did not have the institutional capacity to organize and direct these Crusading armies toward the accomplishment of their “holy mission”. Consequently, there was a need in Christendom for a third party - a transnational military order - to fulfill this role. This organizational entity would hold close relations with both the Church and the various states of Europe, while also being semi-autonomous from each.

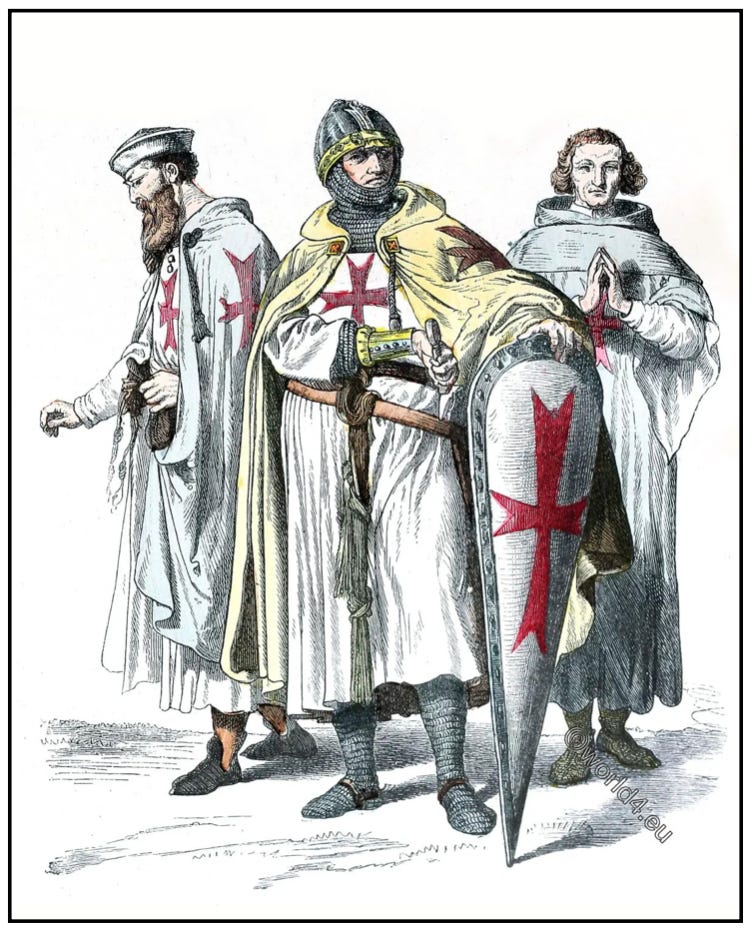

In Europe, three primary military orders arose to meet this challenge. The first and most significant was the Knights Templar, whose regional focus was on Western Europe. After its formation, two other significant orders emerged: the Knights Hospitaller, focused in Eastern Europe, and the Teutonic Knights, focused in the Germanic regions.

While the Knights Templar were outwardly serving as the primary military contractor of the Church, in secret they played another role: aggregators and preservers of the esoteric doctrines of the ancient world.

Like the secret societies of old, the Templars were organized according an esoteric/exoteric polarity, with an outer body that was in formal connection to the papacy of the Roman Catholic Church, serving as its primary military contractor, and an inner body that was connected with underground esoteric societies and initiatic orders in direct connection with the old Mystery Schools.

As Manly Hall explains, “from the beginning, the Knights of the Temple served two doctrines. One was concealed from all except its leaders and certain trusted members; the other, publicly stated and practiced for the sake of appearances, conformed with the regulations of the Church.”

The founder of the Templar Order, Hugh de Payen, had originally been initiated in Syria into an esoteric sect of mystic Christianity (the Johannites) then flourishing in the region, who claimed to be in possession of “the inner mysteries of Christ.”

Like Manes, they “seemed to have derived inspiration from the Nazarenes and certain Gnostic sects that denied the divinity of Jesus, but acknowledged him to be a great and holy prophet. They rejected utterly the Immaculate Conception and other cardinal tenets of the Western Church.”

In regards to Jesus, this sect “claimed to possess ancient records to the effect that when Jesus was a small child he was adopted by a Rabbi named Joseph, who carried him into Egypt, where he was initiated into the occult sciences. The priests of Osiris, regarding him as the long-promised incarnation of Horus expected by the adepts, finally consecrated him Sovereign-Pontiff of the universal religion.”

This sect of mystical Johannite Christians imparted upon the Templar order, at its outset, a grand humanistic mission - one that perfectly restates Plato’s ideal of the Philosophic Empire:

At the time of Hugh de Payen’s initiation, Theocletes was the hierophant of the Syrian Mysteries. Manly Hall informs us that “he communicated to the founders of the Temple the idea of a sovereign priesthood of dedicated and initiated men united for the purpose of overthrowing the bishops of Rome and the establishment of universal civil liberty. The secret object of the Johannites was the restoration of the esoteric tradition and the gathering of mankind under the one eternal religion of the world.”

This belief is clearly a derivation of what the earlier sect of Manichaeans believed and fought for. They, like Manes, “believed in a primitive religion ever-existing in the world, of which formal theologies were corrupted forms. They held that enlightened and purified love was the highest of human emotions, which manifested as a simple and natural love for God in heaven above and for man on Earth below.”

Their secret assemblage, which perpetuated itself through Dark Ages, “was dedicated to the liberation of the human being from all despotism and tyranny. The end to be attained was an enduring brotherhood of mankind.” This ideal was based upon their deep-rooted belief that “all kingdoms and nations should dwell together in peace, governed by just laws and noble examples. All tyranny must end; all false doctrines must fall when the light of Truth - the Christ within - is acknowledged as the Universal Redeemer.”

15. The Symbolism of the Grail Quest

The body of the Templar Order arose from an older surviving military guild from Roman times.

The basic story is that, while crusading in the Holy Land (Palestine), a small order of French knights (with connections to important European families and secret societies) joined together to form a fraternal organization.

This organization would be outwardly disguised as a military order in service to the Roman Church. But inwardly, it would be dedicated to the restoration of ancient wisdom and the reformation of European civilization according to the fulfillment of ancient philosophical ideals.

Thus, using the outer, military body of the Templar Order as a shield, the esoteric leaders of the fraternity performed a variety of secret and covert actions, ones dedicated ultimately toward the goal of bringing about a grand reformation in the political, economic, and cultural affairs of Europe.

Connecting the outer body of the Order with its inner hierarchy were a number of grades or levels, which disciples graduated through sequentially. In this way, the Templars were organized using the same initiatic structure as the old Mystery Schools.

In a recent article for ancient-origins.net, Mark Pinkham expands on the internal organizational design of the Templar Order. He writes that, “while attempting to keep their veil of secrecy tightly drawn, the Templar elite organized their order into a concentric arrangement - consisting of outer and inner circles of initiates. The Johannite hierarchy comprised the three inner circles, while the rest of the knights occupied the seven outer circles.” These seven outer circles corresponded to the lesser Mysteries, while the three higher rings of the organization was reserved for initiates of the Greater Mysteries. (source)

Manly Hall further elaborates, noting that in some instances “the number of degrees was increased … (to) as many as thirty-three grades, somewhat similar to the structure of modern Freemasonry.”

Notably, the system of religious mythology that was followed by the initiates of the Templar Order was not provided by the biblical orthodoxy of the Church they were outwardly serving; nor was it drawn directly from the old pagan religious myths of antiquity. Rather, it was a custom-built myth oriented around the Grail legends - i.e. the Quest for the Holy Grail.

Manly Hall explains that “the Grail legends are intimately associated with the descent of Asiatic and North African mystical Societies through that period now referred to as the Dark Ages. … Like the myths of classical antiquity, these hero tales are sacred rituals belonging to secret Fraternities perpetuating the esoteric doctrines of antiquity.”

The heroes of these legends - the Knights of the Quest - represent initiates of the Mysteries. They were “mythic champions of the human cause” who lived by a monastic code called “chivalry”.

Like the initiates of old, these heroes "performed vigils, cultivated visions, and lived by rules and regulations as rigid as any monastic Order. They had signs and passwords and were bound together by secret vows and obligations. They were dedicated to the protection of the weak, the preservation of righteous peace, and the perpetuation of certain spiritual and philosophical secrets.”

The dictionary of Oxford Languages defines chivalry as “the combination of qualities expected of an ideal knight, especially courage, honor, courtesy, justice, and a readiness to help the weak.” Not coincidentally, these characteristics are also the ones required of initiates of the ancient Mysteries.

In his article “Parsifal and the Holy Grail”, Manly Hall expands on the code of chivalry practiced by the Grail Knights: “The code of the Grail was the religion of service, and this in turn consisted of the rules of chivalry. The knight went alone to a sacred place and there passed an extended period in fasting and vigil. He was called to knighthood by the strength of his own soul, and when he accepted this internal ordination he assumed, at the same time, the regulations of his Order or Brotherhood.”

Like the initiation rites of old, “knighthood was earned by purity and dedication, and those who achieved it were peers and princes of the Invisible Kingdom of the Grail. … (The chivalrous knight) dedicated his life to the weak and oppressed. He became the champion of virtue and innocence. He renounced all material ambition and offered his sword, the symbol of his manhood, to the service of God.”

In a time when Church orthodoxy was the only permissible belief system, the Grail legends gained widespread popularity, despite the fact that the Church is entirely absent from them.

On this note, Hall writes: “Just what was the ecclesiastical status of the Grail kings? … In the High Mass of the Grail no vested clergy is represented, even in a subordinate role. … In the Grail ceremonies, the cup itself is its own high priest, and the knights who serve its decrees are privileged to partake in the solemn sacraments without an earthly intercessor.”

Hall goes on to discuss the core elements of Grail symbolism:

“The symbolism and rituals of the Fraternities of the Middle Age involved a search for something remote or hidden. … The Knights of the Quest were supposed to be seeking a cup guarded by angels, which usually appeared to the pure of heart in a circle of splendid light and song, and veiled with a silken cloth.”

Expanding on the esoteric symbol of the Grail, Hall writes that “the blood of Christ, ever-flowing in the Grail, signified his true doctrine, and the cup which contained it was his Esoteric School, the chalice of his adepts. The search for the Grail was the spiritual adventure of regeneration, and the trials and tribulations of the knights concealed under veiled terms the story of initiation into the spiritual Mysteries of Christ.”

16. The Glory of the Guilds

In the pre-Christian era, the Mystery Schools operated out of the temple complexes of the state religion. They therefore gained their material support from the state. But after the fall of pagandom and the move of Europe into Christianity, church and state became separated. Consequently, the Mysteries were forced to move into a new vehicle in order to perpetuate their doctrines.

In previous chapters of this book, we discussed how the esoteric doctrines of the Greater Mysteries moved into the new institutional vehicle of philosophy. Due to persecution, during the Middle Ages in Europe these philosophical schools required protection and concealment. Therefore, they needed to attach themselves to an outer institutional body which could support and disguise them. For this reason, they embedded themselves within the outer body of Europe’s guild system: a move that the Templar Order helped to facilitate.

As Manly Hall explains, “the persecution of the (Esoteric Schools) scattered the Masters over the entire Continent. They disguised themselves as wandering troubadours, peddlers, merchants, journeymen, artisans, and craftsmen. One of their new strongholds was to come through the guild system, where, through societies of artisans organized according to an apprenticeship system, they worked to seed elements of a Humanist Reformation into the wider body of Western society.”

Since ancient times, economic and artistic activities were organized around a pattern of guilds, which existed as semi-autonomous organizational entities with their own internal governance structures.

Originally, these guilds were an extension of the temple and were not separated from religion, with each profession, craft, and trade guided by a patron divinity.

Hall writes that “in most cases, the original and highly valued secrets of the guild were believed to have been bestowed by one of the gods, and the duties of the guild included special rites and ceremonies. These took the form of rituals of gratitude and homage.”

Hall further notes that “there are many reports that the gods themselves favored exceptionally talented devotees, appearing to them in dreams or impressing upon their minds rare and precious revelations.”

In their oldest forms, these guilds were comprised of families or clans who perpetuated the “choicest formulas, recipes, and techniques” within their bloodlines.

But gradually, as society enlarged and became more complex, this pattern expanded beyond the family or clan. “Ability rather than birth was now the indispensable prerequisite. Instead of the family forming the guild, the guild created a new kind of family, made up of those bound together by similar interests and abilities.”

Hall further elaborates on the inner organizational dynamics of these guilds:

“Each of these guilds was a closed corporation which could only be approached by the long, tiresome road of apprenticeship.”

The guilds were divided into grades based on skill and merit. “These grades served as a kind of ladder, and those learning the profession or trade advanced by experience from one degree to another until they reached their maximum degree of skill.”

“When a man became a master in his guild he was an important citizen, respected and respectable. Frequently, he was surrounded by a constellation of apprentices who considered it a signal honor to gain their training from a renowned master. This was a kind of craft Masonry. The master estimated the ability of his apprentices, confiding his choice secrets to the more promising.”

One might recognize in this hierarchical scheme of levels or grades the same initiatic pattern of the old Mystery Schools.

Guilds perpetuated themselves across generations by means of the apprenticeship system - an intimate pedagogical relationship pattern derived from the Esoteric Schools and their archetypal pattern of guru and disciple.

In the highest and innermost aspect of the governance structure of these guilds was a Philosophic School, which taught a doctrine of philosophy based on the tools and patterns of the trade in question. Of course, the guild of Masons is the hallmark example of this, with the members of this ancient order revering God as the Great Architect of the Universe.

The Templars, covered previously, were also a type of guild - a military-themed one. The extent of their operations expanded beyond just combat-related activities, however. They were more like a “guild of guilds” - i.e. an umbrella organization under which a variety of subsidiary guilds were drawn together and brought into alignment.

Historian Joseph P. Farrell describes the Templars as “a kind of extra-territorial ‘United European’ bureaucracy. … Like a modern transnational corporation, it featured extra-jurisdictional and extra-territorial status.”

Under their umbrella, various trade and craft guilds operated within different specialized areas of economic and cultural activity. Through the Templars, these guilds were brought into a common pattern of linkage across regions, industries, and trades.

One example of a prominent guild operating during the Middle Ages was the Troubadours. The origin of the Troubadours can be traced back to pagan times with the Bards, which was one of the three branches of the ancient Druidic Order. “They were the wandering poets and minstrels, the singers of the Mysteries, concealing profound spiritual truths under gay songs, stories, fables, and myths.”

The Troubadours were the originators of the Grail legends, covered above. Wandering from castle to castle, they spread the doctrine of chivalry among the noble classes of Europe - right under the nose of the Church.

As Hall explains: “Beneath the surface (of their hero-myths) was the doctrine of the rights of man. … From the Troubadours came many of those glorious myths and legends of the Age of Chivalry, the moral fables that right always conquers, and nobility of spirit is the only true nobility to which man can attain.”

Another important medieval guild was the Craft Masons. These were the cathedral builders, who flourished during the medieval era predominantly in Germany and England.

This guild dates back to the Dionysian Mystery cult of ancient Greece. This ancient fraternity of artisans were “peculiarly consecrated to the science of building and the art of decoration. Acclaimed as being the custodians of a secret and sacred knowledge of architectronics, its members were entrusted with the design and erection of public buildings and monuments … They were regarded as the master craftsmen of the Earth.”

“The supreme ambition of the Dionysian Architects was the construction of buildings which would create distinct impressions consistent with the purpose for which the structure itself was designed. In common with the Pythagoreans, they believed it possible by combinations of straight lines and curves to induce any desired mental attitude or emotion. They labored, therefore, to the end of producing a building perfectly harmonious with the structure of the Universe itself.”

During the Middle Ages, this fraternity of builders would take on contracts from ecclesiastical authorities to build magnificent churches, yet they operated autonomously from the Church’s oversight and practiced their own form of self-government.

In their innermost recesses, the medieval Masonic guilds practiced esoteric rites descended from antiquity. So, while on one hand they were employed by the Christian Church in their cathedral building activities, on the other hand they quietly held philosophical views and practiced ancient religious rituals that the Church would have found blasphemous.

They did not revere the God of the Christian Bible, but rather “venerated Deity under the guise of a Great Architect and Master Craftsman, who was ever-gouging rough ashlars from the fields of space and truing them into universes.”

In addition to their role of preserving and perpetuating the Esoteric Doctrine during the Dark Ages, the guilds of medieval Europe were also responsible for helping regional economies and local cultures to organize and develop.

Within the cities, communities, and hamlets of Europe, the guilds fostered progressive humanistic ideals, liberal enterprise, and pragmatic skills and trades. They “formed protective associations to maintain fair standards of merchandizing and protect members from unfair business practices.” These important sociocultural elements would in time blossom to become core pillars of the modern world order.

Hall elaborates, explaining that “the guilds were the champions of the human cause. (They were) institutions of fair play and honest practice. They were co-operatives, … and their guild masters legislated the life of the time.”

“All the guilds served human needs, and were in agreement on a broad program of ethics. To these men, fair business practice was a part of religion. To be masters in good standing they had to lead blameless lives under the constant observation of their fellow townsmen. An unworthy action not only disgraced the master but cast a reflection upon his guild, and his brother workers shared in his disgrace.” In this way, the guilds served as a powerful character-building force within a medieval Europe that was in desperate need of it.

Together, the entire apparatus of guilds, existing under the umbrella of the Templar Order, formed the outer body of one great Mystery School.

Hall explains that “the guilds themselves were not actual embodiments of the esoteric associations but rather instruments to advance certain objectives of the divine plan, especially the accomplishment by man of such self-improvement as was immediately necessary.”

In this way, "these Orders of Fraternity were attached by slender and almost invisible threads to the parent project.” This parent project dates back to the original aims of the Manichaeans and their predecessors in the ancient pagan Mysteries Schools, which was to build a democratic commonwealth of world nations dedicated to the glory of the One God.

Hall asks, “What better place could be found in which to plant the seeds of the democratic dream? From these small centers of self-government might flow the concept of the World Guild, the World Commonwealth, and indeed the Philosophic Empire.”

17. The Albigensian Crusade and the Fall of the Templars

While the Templars and the various guilds they protected were a trans-European force, the leadership behind the order covertly worked to establish a homeland in southern France. This “Templar state” became the basis of the Cathar community, also known as the Albigensians.

This quasi-utopian community “spread throughout Southern France during the 12th century and certainly originated among the secret adepts of Manichaeism. … (In this group) there was a confusion of religion, philosophy, democracy, and trade unions, all bound together as a kind of primitive church fraternizing with similar groups in the Netherland and along the German Rhine.” (MPH)

This community, through their association with the Templars, grew rich and prosperous and developed ambitions to “make use of the Crusades as a means of setting up Jerusalem as the capital of the spiritual world, thus unseating the supremacy of Rome.” (MPH)

Realizing the existential threat that the Cathar community represented to their hegemony over European society, the Church, in conjunction with various sympathetic monarchs and nobles, set out to destroy them.

The Inquisition was set up in large part to quash this heretical motion from spreading. As Joseph P. Farrell explains, ”a significant local region was breaking away from the international cultural, political, financial, and cosmological order that the papal ecclesiastism represented.”

Around this period (~13th century), the Church seems to have also realized that the Templars, who they originally thought were their allies, were actually conspiring against them. They therefore set out to destroy not only the Cathars but also the Templars.

Hall explains that “we know that the massacre of the Knights Templars (and the Cathars) had several motivations. First, the confiscation of their wealth and holdings throughout Europe; second, to protect both the church and state from a major reform with humanistic implications; and third, to protect European theology from a major renovation.”

Joseph P. Farrell describes the massacre of the Albigenses as “one of the vilest and bloodiest acts of genocide and mass murder ever perpetrated in human history.”

He writes that, during the siege, “princes, counts, viscounts, barons, nobility, and rabble from all over western Europe converged on the Languedoc (a region of southern France serving as the Albigensian stronghold), assured of papal dispensations for their butchery, and of plunder and booty.”

His account continues: “In the houses of God, where priests adorned with ornaments celebrated the mass for the dead, all the inhabitants of the town were murdered: men, women, and children (“Twenty thousand,” wrote Arnaud de Cîteaux to the Holy Father). Nobody was left alive. Even the priests were burned alive before the altar. … The town was sacked. While the crusaders were fully occupied with their work as executioners in the churches, robbers devoted themselves to pillaging the town.”

The Templars were destroyed soon after the Albigenses, with many of their knights hunted down, captured, and burned at the stake. But the order was not destroyed completely; much of its wealth and assets, along with many of its initiates, survived and went underground, to become the instruments through which future campaigns of the Philosophic Empire would be enacted.

18. The Italian Renaissance

During the late Middle Ages, there arose another set of powers on the European scene, one that emerged alongside the rise of the Templars but was separate from them. These were the powerful merchant banking families rooted in the north Italian city-states of Genoa, Florence, and Venice.

These powerful banking dynasties orchestrated a lucrative shipping, trade, and banking business, which connected Europe with Byzantium and Arabia. In these latter regions, these wealthy families came across many of the same lost pagan philosophical works and ideas that the Templars had originally discovered during the Crusades. These include works from Neoplatonism, Hermeticism, Cabalism, and others.

During the 15th century, these Italian oligarchs, most notably the Medici family of Florence, brought these works back to Europe, where they were seeded into various secret societies and artisanal guilds, launching the Renaissance as a result.

The center of this cultural revival came in the form of a Platonic-style Academy founded in Florence in the second half of the fifteenth century under the financial patronage of Cosimo de Medici and the intellectual leadership of Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola.

The primary effect of the Renaissance was that it launched a philosophical movement within the aristocratic classes of these Italian city states. This intellectual movement then spread throughout the upper classes of other European regions, creating a widespread interest in ancient knowledge, humanistic thinking, and natural philosophy among key segments of European aristocratic society.

As philosophic historian Richard Tarnas explains, “with the influx of this tradition came a new vision of man, nature, and the divine.” Man began to see “nature as permeated by divinity … (and) by a mystical intelligence whose language was number and geometry. The garden of the world was again enchanted, with magical powers and transcendent meanings implicit in every part of nature.”

Hall notes that the grand theme of the Renaissance was the “rights of man”: “Each had found a kind of freedom to think, to live, to dream, to hope and to suffer and die if necessary in order to preserve his inalienable liberties. There was an incentive to improve, to build for the future, to leave a better heritage, and to aspire to a better destiny. The medieval caste-system had lost significance. There was less of serfdom and the divine right of kings, and more of citizenship and the divine right of men.”

Tarnas offers further elaboration on the political implications of this transformation taking place within elite European thinking: “The state itself (came to be) seen as something to be comprehended and manipulated by human will and intelligence, a political understanding making the Italian city-states forerunners of the modern state. … It was thus from these origins in the dynamic culture of Renaissance Italy that there developed a distinctive new Western personality. Marked by individualism, secularity, strength of will, multiplicity of interest and impulse, creative innovation, and a willingness to defy traditional limitations on human activity, this spirit soon began to spread across Europe, providing the lineaments of the modern character.”

Ultimately, the Renaissance would inspire a number of significant transformations within the culture and thought of elite European society, ones that were humanistic and scientific in nature and thus heretical to the interests of the Church and monarchy.

The Renaissance had a marked effect on transforming the psychology of elite European society. But its impact was largely on the aristocracy. As Manly Hall explains, “the Renaissance represented a motion from the top. Its leaders were generally persons of influence, authority, and attainment. Like Lorenzo de’ Medici, for example, the leaders made the new learning available first to their own circles and then to the public.”

Thus, it was the nobility, rather than the state or church, who catalyzed this intellectual motion in Europe. “The nobility found it desirable to strengthen its own position (against the Church) by becoming patrons of progress. The great families created schools and universities, endowed scientific research, and became the sponsors of creative genius.”

While its effort to undermine the Church within the hearts and minds of the aristocracy was a success, what resulted was an imbalanced progression of culture, with the great awakening not trickling down into the lower castes of society. Another movement was needed for them, one that was not philosophic and intellectual in nature but rather moralistic and religious. This would come with the Protestant Reformation, which we will turn out attention to next.

19. The Protestant Reformation

At nearly the same time that the Italian Renaissance was taking place (the 15th century), the Italian banking dynasties behind the Renaissance, almost certainly in coordination with remnants of the old Templar order working in the shadows, also became involved in organizing and financing a number of important interrelated activities and events across Europe.

Tarnas summarizes the activities of this period: “Within the span of a single generation, Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael produced their masterworks, Columbus discovered the New World, Luther rebelled against the Catholic Church and began the Reformation, and Copernicus hypothesized a heliocentric universe and commenced the Scientific Revolution.”

These momentous occurrences had the effect of destabilizing the old psychological and sociological patterns of Europe. What resulted was the gradual move of Europe out of the Dark Ages. The days of the Church and State possessing absolute rulership over western civilization were coming to an end. New interests, ideas, and beliefs were coming to the forefront, ones that would in time “form into a pattern which we call the modern world.” (MPH)

While the Renaissance catalyzed an intellectual transformation within the upper classes, it was the aforementioned Protestant Reformation that was tasked with transforming the mind state of society’s lower rungs.

While the Renaissance was inspiring the aristocratic elite of Europe with the rediscovery of philosophic wisdom from ancient pagan times, the Reformation was concerned with something different: reforming the medieval Church away from its decadent and self-aggrandizing behavior and back toward the simpler and “purer” Christian values espoused by the early Christian Fathers.

In his book Passion of the Western Mind, Richard Tarnas summarizes the tense relationship between the Church and the greater body of European society that had been developing during the decades preceding the onset of the Protestant Reformation.

“Having consolidated its authority in Europe after the tenth century, the Roman papacy had gradually assumed a role of immense political influence in the affairs of Christian nations, … with the papacy actively intervening in matters of state throughout Europe, and with enormous revenues being reaped from the faithful to support the growing magnificence of the papal court and its huge bureaucracy.”

“The Church hierarchy was visibly prone to financial and political motivation. The pope’s temporal sovereignty over the Papal States in Italy involved it in political and military maneuverings that repeatedly complicated the Church’s spiritual self-understanding. Moreover, the Church’s extravagant financial needs were placing constantly augmented demands on the masses of devout Christians. Perhaps worst of all, the secularism and evident corruption of the papacy were causing it to lose, in the eyes of the faithful, its spiritual integrity.”

“In the meantime, the secular monarchies of the European nation-states had gradually gained power and cohesion, creating a situation in which the papal claim to universal authority was inevitably leading toward serious conflict.” Overall, there was a “growing divergence between the ideal of Christian spirituality and the reality of the institutional Church.”

This was the situation that the Protestant Reformation sought to address.

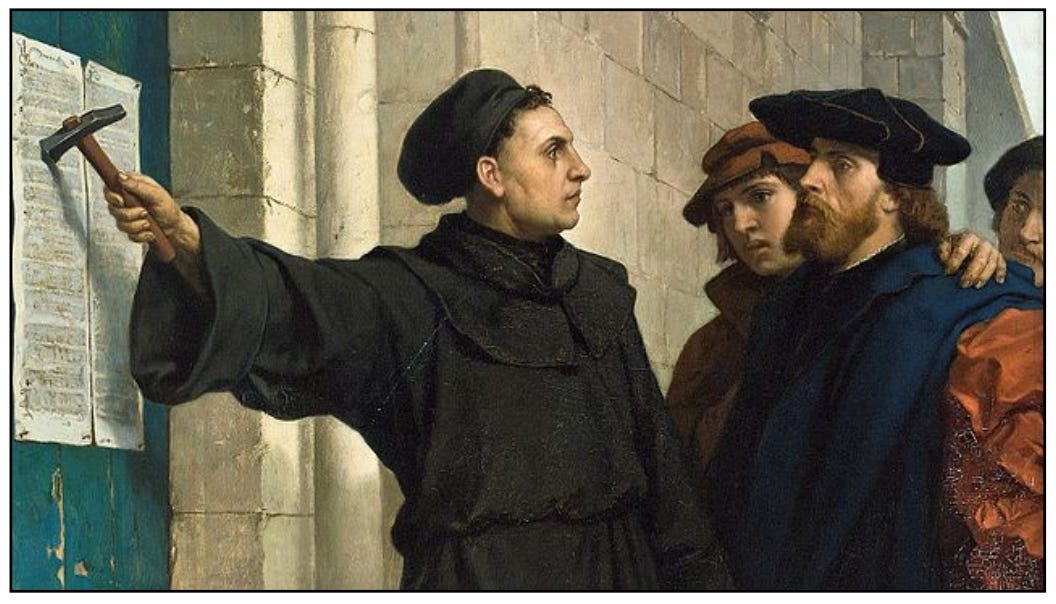

Tarnas explains that, during the Reformation, “Luther defiantly confronted the Roman Catholic papacy’s patent neglect of the original Christian faith revealed in the Bible. Sparked by Luther’s rebellion, an insuperable cultural reaction swept through the sixteenth century, decisively reasserting the Christian religion while simultaneously shattering the unity of Western Christendom.”

In retrospect, it is clear that Luther was not acting alone but rather represented a growing faction within Christendom against the excesses of Rome. This faction sought to disseminate the idea that spiritual salvation was granted not merely by one’s participation in the Church but rather by faith in the Holy Scripture.

Thus, the primary emphasis of the Reformation was to destroy the idea that the Roman Catholic Church was the exclusive arbiter of Christian truth. The new technology of the printing press became significant in spreading this message: it allowed the ideas of Luther and other intellectual leaders of the movement to spread widely and rapidly, thus eroding the monopoly on biblical interpretation and learning long held by the Church.

Hall indicates that covert networks of Templars and other sympathetic organizations were intricately involved in seeding the spread of the Reformation movement.

After their persecution by the Church, the remnants of the Templar Order “began assembling themselves in small and secret groups to carry on their thought among those congenial with it.” These covert networks would in time have a hand to play not just in the founding of the Renaissance, but also the Reformation.

Hall writes that “the secret schools, broadly Gnostic in their convictions, must have permeated the whole of Europe and entered into the guild life of the traders and artisans; otherwise it is impossible to account for the spontaneous support given to the Reformation.”

It is notable that the rising Protestant faction in Europe shared several of the same values and concepts that had been originally been fostered by the medieval guilds. Consequently, these two groups - the Protestants and the guilds - aligned with each other. They were brought together through bonds of sympathy, resulting in a clear demarkation between progressive and conservative forces within European society.

What resulted was a polarization of Christendom in Europe, with allegiances divided between conservative forces seeking to maintain the status quo and progressive forces seeking to seed humanistic values into the collective life of Europe, while at the same time deconstructing the Church’s hegemony over Western Civilization.

Tarnas explains that “with the Reformation, the universal ambition and dream of the Catholic imperium was finally defeated. The resulting empowerment of the various separate nations and states of Europe now displaced the old ideal unity of Western Christendom, and the new order was marked by intensely aggressive competition. There was now no higher power, international and spiritual, to which all individual states were responsive.”

He continues: “The Reformation opened the way in the West for religious pluralism, then religious skepticism, and finally a complete breakdown in the until-then relatively homogenous Christian worldview…. From here on, each believer’s belief was increasingly self-supported; and the Western intellect’s critical faculties were becoming ever more acute.”

While the Reformation did represent a definite forward progression for European society, it did come in conflict with several key aspects of the Renaissance.

Hall notes that the Reformation involved an “extreme religious intensity”, one whose “heavy hand” attacked “music, drama, literature, and philosophy, and imposed limitations upon scientific research.”

For this reason, the philosophical and intellectual breakthroughs of the Renaissance became confined to certain networks of families within Europe’s upper classes. Meanwhile, the lower classes remained committed to orthodox Christianity. But this orthodoxy was now segmented between Catholics and Protestants.

The Protestant factions within Europe, centered most of all in Germany and England (the two foremost centers of guild activity), came to support key progressive initiatives long desired by the Templars and other philosophical groups. These included nationalism, economic development, and rational inquiry: all key features of what would later become our modern scientific age.

Tarnas explains that “the Reformation had succeeded not least because it coincided with the potent rise of secular nationalism and German rebelliousness against the papacy and the Holy Roman Empire.”

As a consequence of Christendom fractioning into competing camps, it became up to individual states to decide which faction they were going to embrace. In this way, as Tarnas writes, “the individual secular state now became the defining unit of cultural, as well as political, authority. The medieval Catholic matrix unifying Europe had disintegrated.”

In his book Passion of the Western Mind, Tarnas describes at length the lasting implications that the Reformation had on the political and cultural landscape of post-Renaissance Europe.

On the Reformation’s lasting legacy of separating church and state, he writes: “With secular rulers now defining the religion of their territories, the Reformation unintentionally moved power from church to state, just as it did from priest to layman. And because many of the principal monarchs chose to remain Catholic, their continuing attempts to centralize and absolutize political power caused Protestantism to be allied with resisting bodies - aristocrats, clergy, universities, provinces, cities - that sought to maintain or increase their separate liberties. Hence, the cause of Protestantism became associated with the cause of political freedom.”

And on the role that Protestantism would eventually play in the economic development of Europe, he writes: “The Protestant work ethic, along with the continued emergence of an assertive and mobile individualism, had played a major role in encouraging the growth of an economically flourishing middle class tied to the rise of capitalism. The latter, already developing in the Renaissance Italian city-states, was further propelled by numerous other factors - the accumulation of wealth from the New World, the opening up of new markets, expanding populations, new financial strategies, new developments in industrial organizations and technologies. In time, much of the originally spiritual orientation of the Protestant discipline had become focused on more secular concerns, and on the material rewards gained by its productivity. Thus, religious zeal yielded to economic vigor, which pressed forward on its own.”

These byproducts of the Reformation were not accidental. Rather, they were targeted initiatives of the Esoteric societies - part of a great plan pursued by them with patient diligence over a long period of time. The aim of their long-term plan is clear: the gradual transformation of civilization into Plato’s ideal - the Philosophic Empire.

20. The Rise of the Rosicrucians

The restoration of esoteric philosophy during the Renaissance, sparked by the founding of Ficino’s Academy in Florence, gradually spread westward over subsequent decades, moving through continental Europe toward England.

The great Baconian scholar Peter Dawkins has tracked the westward motion of this stream of esoteric knowledge. He notes that the ancient wisdom teachings brought into Europe during the Italian Renaissance initially moved northward into the Germanic regions by Abbott Johannes Trithemius. This German occultist became the initiator of three important figures of the 16th century: Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, Paracelsus (the famous healer), and Giordano Bruno (the famous Hermetic scientist).

Dawkins states that it was Agrippa who brought the wisdom teachings to England in 1510, founding a secret society there to preserve them, after having initially founded a similar society in Paris a few years earlier. Sir Thomas More, the author of the famous book “Utopia”, was the leader of this original society in England, establishing a school there in the early decades of the 16th century.

One of the members of this English esoteric school was John Dee, the mysterious sage of the royal court. Another was a man named Nicholas Bacon, an important courtier connected with the political elite of the time and someone who would eventually be named to the privileged position of “Lord Keeper of the Great Seal” during the reign of Queen Elizabeth.

Dawkins states that the Rosicrucian Society was formally founded in 1572 from members of the initial esoteric society established by Agrippa and More in 1510.

Dawkins notes that this occasion - the formal founding of the Order - was marked by a great supernova event in the constellation of Cassiopeia in the year 1572. This constellation is associated with the “Heavenly Queen”, and sages at the time “recognized it as the sign of the birth of a great light in the world, born of the Heavenly Queen. This was associated in a worldly way with the queen of England, Elizabeth I”, who was secretly Francis Bacon’s real mother.

Being students of astrology, the esotericists in this society perceived this auspicious event as a sign to mobilize, with Francis Bacon, still a child at this point, conceived as the guiding light or “Apollo” of this order. Thus, the 1572 supernova marked the formal beginnings of the Rosicrucian society.

Earlier in the 1500s, the Swiss healer Paracelsus, mentioned above, made an astrological prophecy based on his accurate prediction that a significant planetary conjunction of Saturn, Jupiter, and Mars would take place in the sign of Sagittarius during the year 1603.

Paracelsus predicted that, at this point, a great, enlightened soul would appear - an adept of the alchemical arts. In the lore of alchemy, this great alchemical adept was given the symbolic name “Elias the Artist”.

In his prophecy, Paracelsus made the cryptic prediction that, during the time of the 1603 planetary conjunction, “God will permit a discovery of the highest importance to be made; (but) it must be hidden until the advent of Elias the Artist.”

Dawkins notes that Elias the Artist corresponds with what the Buddhists would term a Bodhisattva:

“‘Elias’ is an alternative form of the name Elijah. In cabalistic tradition, the prophet Elijah is associated with Enoch, who is referred to as the Great Teacher. According to this tradition, Enoch was the first human being to attain all the degrees of initiations and ascend bodily into the highest heaven. … Given the choice of rising further and reuniting totally with the Godhead, or remaining with and teaching the rest of humanity, Enoch chose the latter out of his love for humanity.”

He also notes that the role of Elijah or “Elias the Artist” is that of the initiator: his task is “that of opening hearts in love and guiding souls through initiation, preparing them for their initiatory death, resurrection, and illumination (when they will see the Messiah in glory).”

At the appointed time, in 1603, this triple conjunction did indeed take place, alongside with another significant supernova event - one taking place in the constellation of Cygnus, the Swan. This supernova was then followed by a second, in 1604, this time in the constellation of Ophiuchus, the “serpent master”.

Dawkins writes that the “Rosicrucians took (these auspicious events) to mean that they could now announce to the world their work, prepared in secret (since 1572), and begin the instauration (or revitalization) of the whole wide world by means of the reformation of all arts and sciences.”

As we will see, this ambitious project would later be outlined by Francis Bacon, the great spiritual master of this Order and the awaited incarnation of Elias the Artist, in his work “The Great Instauration”.

Before moving on, it is notable to consider that, in the first Rosicrucian manifesto (“Fama Fraternitatis Rosae Crucis”, published in 1614) the year 1604 is specifically indicated as an important date.

In the mythological story presented in this work, 1604 is the year that the lost tomb of Father CRC, the symbolical figure who is said to be the founder of the Rosicrucian Brotherhood, is rediscovered and opened. Allegorically, this “opening of the tomb” represents the door of the Mysteries being re-opened after a period of closure and obscuration.

As MPH puts it, through Father CRC (a veiled reference to Bacon) “the old Mysteries (an imperishable institution) had emerged again from the womb of time.”

21. Francis Bacon, the Rosicrucian Messiah

Francis Bacon was born on January 22nd, 1561 as the secret child of Queen Elizabeth I, the “Virgin Queen”, and Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. For various political reasons, the relationship between Elizabeth and Robert could not be publicly disclosed, nor could the fact that they sired an offspring together be revealed. Therefore, Bacon (whose real name was Francis Tudor) was given over to be raised by the aforementioned Nicholas Bacon, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, and his wife, with the Queen keeping a close watch over him throughout his young life.

Nicholas Bacon, being a member of the Rosicrucian Order, had young Francis educated in the fundamentals of ancient philosophy and esoteric knowledge from an early age, preparing him from the outset to become an initiate of their Order.

As Peter Dawkins explains, Francis and his elder brother (by adoption) Anthony “were brought up, educated, and trained as initiates in Sir Nicholas’ Orphic-Platonic Academy, with Francis in particular being recognized as the Elias the Artist prophesied by Paracelsus, who would one day take on the leadership of the Rosicrucian Fraternity - which indeed he did.”

From the start, Bacon was recognized as a prodigy and genius, and every care was taken to give him the best education possible, including enrolling him at university (which he attended starting at age 12) and, later, sending him to France to continue his education with an esoteric society of artists, philosophers, and humanists flourishing there at the time.

It was during his stay at university that the great supernova event in Cassiopeia (in 1572) took place. According to Peter Dawkins, during this supernova young Francis received a profound spiritual vision of what his life’s work would be. Since this singular event, the young prodigy dedicated all his efforts to fulfilling this spiritual destiny.

Peter Dawkins outlines the contours of Bacon’s vision: “Francis’ grand idea and mission, therefore, was a renovation of all arts and sciences based upon the proper foundations, one which, by means of a special method that he was to test out and then teach, could then spread to other countries for the benefit of the whole world. It was a truly grand concept - one he was later to call ‘The Great Instauration’ or ‘Six Days Work’.”

In terms of his formal, public career, which he would begin upon his return from France, Bacon became a lawyer in the royal court. In time he attained the highest honors of his country, including those of knighthood, baron, and later viscount. Later in life, he was appointed Lord High Chancellor, placing him second in power to the crown and making him “virtual ruler of England and the most powerful man in the kingdom.” (MPH)

As a result of his early travels on the Continent, his connection with the Rosicrucian Order in England, and his work with England’s royal court, Bacon gained access to all the vital information he would need to consummate his Great Work. No other person of his time held such valuable connections: he was linked into the intel of England’s political, legal, and military-intelligence networks, while at the same time he was connected with numerous artistic, intellectual, and philosophical societies existing in both England and on the mainland Continent.

Thus, as Dawkins points out, Bacon “was at the heart of and privy to a huge web and databank of intelligence on all kinds of matters, from politics, economics, law, trade, history, geography, science, literature, poetry, military strength, religious beliefs, social customs,” etc, both at home and abroad.

This incredible databank of knowledge, as well as his extensive connections, would be leveraged by Bacon with great effect as he planned and carried out his Great Work.

While his formal accomplishments in the service of the crown are impressive, the most important elements of Bacon’s life’s work were done in secret and deliberately concealed. His accomplishments in this hidden realm of his career are remarkable and include the following:

a) He developed a formal method for the advancement of science. In this effort, he not only wrote out the philosophical foundations for the scientific method, but he also founded the first formal scientific organization in Europe - the Royal Society.

b) He instigated an “English Renaissance” by elevating the state of English culture and language. As we will later explore, he accomplished this in part through his own writings but also by organizing a secret society of poets and guiding them toward the creation of the groundbreaking Shakespeare plays, among other works.

c) He worked to ensure the rise of England as a progressive force against Spain’s alliance with the conservative Catholic Church. Part of this mission included working to ensure that it would be England, not Spain or Portugal, who would win the battle for American colonization.

d) As part of this effort, he helped to plan and establish the American colonization scheme, which he fulfilled through his participation in founding and directing the early activities of the Virginia Company. He also wrote the charter for England’s first colonies in America.

e) He re-organized, expanded, and surfaced important secret societies such as the Rosicrucian Order and the Freemasons, two groups with whom Bacon had intimate contact and for whom his society of poets developed core aspects of their literature and symbolism.

f) He edited the King James Bible in 1611, providing it its literacy excellence.

g) He developed a formalized plan for the eventual restoration and revitalization of global society. This was a his true life’s work and is captured in various publications associated with “the Great Instauration”.

Overall, summarizing Bacon’s vast achievements in so many different fields, Manly Hall writes: “It is rare to find a man who can attain greatness in several departments of learning. In the case of Bacon we find combined in equal excellence the orator and the writer, the philosopher and the scientist, the statesman and the poet.”

It is hard to overestimate the significance that Francis Bacon has had on the evolution of Western Civilization. This was a man born to accomplish and fulfill a Great Alchemical Work - the reformation, transformation, and transmutation of world society.

As the great Adept once said of himself, “I thought myself born to be of advantage to mankind.”

His contemporaries wrote of him with adoring reverence. For example, William Rawley, Bacon’s chaplain and personal friend, wrote: “I have been induced to think, that if there were a beam of knowledge derived from God upon any man in these modern times, it was upon him. For though he was a great reader of books, yet he had not his knowledge from books, but from some grounds and notions from within himself.”

Ben Jonson, a member of Bacon’s secret society of poets, wrote the following tribute to Bacon: “My conceit of his person was never increased toward him by his place or honors. But I have and do reverence him for the greatness that was proper to himself, in that he seemed to me ever, by his work, one of the greatest men and most worthy of admiration that had been in many ages.”

Manly P. Hall, the great esotericist of 20th century America, also held Lord Bacon in the highest esteem.

In a 1941 article titled “Francis Bacon, the Incredible Lord”, Hall writes: “The more deeply we study Bacon’s life and works, the more apparent it becomes that he was a completely unified human being. Although he excelled in several departments of knowledge, his numerous roles were suspended from one sovereign purpose. Necessity often dictated his selection of methods, but the ends to be accomplished were clear and unchanging. He played many parts, always with consummate skill. … His purposes were all parts of one purpose - the restoration of the Philosophic Empire.”