The Mandala: An Image of the Invisible (5 of 6)

Part Five: The Tetractys: Pythagoras's Mandala of the Universe

27. The Tetractys: the Grand Mandala of the Pythagoreans

Pythagoras, the great Grecian sage who first brought philosophy to the Mediterranean region around the 6th century BC, was, before his formal teaching career began, a widely travelled initiate of many of Eurasia’s greatest Mystery Schools.

Pythagoras was not only an initiate of the Greek mysteries, but also traveled extensively and gained initiation into the esoteric schools of Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, and perhaps even India. Manly Hall notes that “there is an account … that Pythagoras reached India and was initiated into the mysteries of the Brahmins at Elephanta in the harbor of Bombay and in the caves of Ellora in the Hyderabad Deccan.”

As an initiate, Pythagoras would have to have mastered to the mystical disciples of the various esoteric schools he had encountered. These mystical disciplines he brought back to Greece, where, like Gautama Buddha, he entrusted them to a small society of elite students who would secretly preserve and perpetuate these meditational disciplines within the inner body of the Pythagorean order.

Manly Hall elaborates: “Pythagoras … was the first Western sage who introduced special disciplines of meditation, concentration, and retrospection. As taught by Pythagoras, these mystical exercises were essentially the same as those practiced by the Brahmins. Like these Eastern scholars, Pythagoras approached religion scientifically and developed a formula or method for the enlightenment of his students. He clearly differentiated between learning as a means of increasing knowledge and learning as a means of releasing directly the spiritual potentials of the human being.”

As we’ve been exploring throughout our multi-part series on "Mandala Design and the Philosophy of Meditation”, esoteric meditation disciplines have long been associated with the use of special emblems termed “mandalas”, which are visual designs of spiritual archetypes.

The use of mandalas in occult meditation practices is calculated to direct the meditating disciple toward a mystical comprehension of universal realities and principles.

Different traditions have different specialized mandalas that they use to communicate the inner mysteries of their doctrines to their disciples. In the case of Pythagoras, the favored mandala of his philosophical school was a simple ten-dot triangular diagram termed the Tetractys.

Manly Hall explains that the “Pythagoreans bestowed great thought upon the Tetractys, or pyramid of ten dots, which they held to be the key to universal mysteries.”

“The Pythagoreans took their most solemn oath upon the Tetractys, which to them was the most sacred of all symbols and the proper figure by which Deity might be most perfectly apprehended and honored.”

To them, the Tetractys was the supreme symbol of universal forces and processes, with its ten dots numerically representing “the sum of all parts and the completeness of all things”. As such, it was for them the perfect symbol of the inner workings of the Divine Mind in Space.

The numerical principles that the Tetractys constellates together in its design “were primarily intended to stimulate ideas. … The mind, attracted to an object for the consideration of its numerical attributes, was invited by the numbers to investigate and admire those celestial causes which precipitated its corporeal appearance.”

The Pythagorean’s portrayal of these celestial causes as numbers rather than images is intentional, as “numerals convey the sense of quality and quantity without the impediment of form or the limitations of place and time. Thus, through a study of numerical philosophy, one’s eye of internal perception may be opened without the mind being filled by erroneous concepts resulting from grosser forms of symbolism.”

In sum, “through meditating upon the mystery of numbers, knowledge was increased, arrangements and proportions made evident, and most obscure secrets revealed.”

The core design of the Tetractys consists of the numerals 1 through 9, plus an additional principle which can be evaluated as either 0 or 10. Whether one evaluates this additional principle as 0 or 10 affects how one deciphers the meaning of the Tetractys diagram.

For this reason, the Tetractys has two possible forms of interpretation: when 0 is added to the numerals 1 through 9, the Tetractys essentially takes on the same meaning as the Diamond Mandala discussed in our previous article: it represents the internal dynamics of First Cause, by which the Divine Being behind the Universe (the Monad; Vajrasattva; Mahavairocana) is first brought into existence.

When the 0 is substituted for the numeral 10, the meaning of the mandala changes, as does the positioning of the numbers within the diagram. Here, the number one moves to the apex position and the Tetractys transforms to become an image of the Divine Self or Monad. This represents the Divine Self existing overtop the world of creation as the One over the All.

In other words, in this second, alternative form, the Self is portrayed in its aspect of internal generation. Here, the Self becomes the host and ruler over creation and the divine hierarchy that governs it. In this manner, this second form of the Tetractys mandala functions somewhat like the Womb or Matrix Mandala of the Mahayana Buddhists, which similarly depicts Mahavairocana in his state of active becoming.

In our coverage of the Tetractys in the sections below, we will first analyze its higher spiritual interpretation as a symbol of First Cause, before later transitioning and looking at it from the other perspective, that of the Divine Self in its process of internal meditation (i.e. active generation).

28. The Tetractys as a Mandala of First Cause

As we covered extensively in our earlier chapter on Pythagorean philosophy, the Pythagoreans grounded their teachings about the “spiritual cosmology” of the world using a precise framework of number, mathematics, and geometry.

While it may sound rather droll or uninspiring to look at spiritual concepts in numerical terms, remember that Pythagoras was also a master initiate of the esoteric schools of his time. The numerical principles he taught symbolize divine principles or archetypes that can be tapped into during the mystical experience.

Thus, “the whole field of arithmetical speculation had to do with the internal growth of the person. It made possible the exploration of qualitative factors, not merely the assessment of quantities. Therefore, it was the foundation upon which must be built the most advanced type of” meditational practice.

The numerical principles depicted in the Tetractys represent mental or psychological archetypes. The world itself is conceived to exist as a projection of these archetypes: its various kingdoms being merely these archetypes clothing themselves in various garments of material form.

Archetypes pre-structure the design of all forms that come into existence within Space. Space is really Consciousness, and the world of form is really a “thought form” that exists within the Mind of this Consciousness. Archetypes represents the patterns of Mind by means of which Consciousness projects and builds its cosmic thought form.

In esoteric philosophy, Creation is understood to exist as the end-product of a divine process of meditation in which God “projects the world by visualization, or by the power of will and Yoga.” This projection takes place via the seven “builder gods” or “Elohim”, which in Mahayana Buddhism are termed as the Celestial Buddhas or Dhyani Buddhas (meditating Buddhas).

The Tetractys is intended to depict this archetypal creation process in mandalic form. In its ten dots are captured the threefold nature of the Divine Self and the seven Rays or principles of Mind which are projected out from it at the onset of creation.

The idea is that the seven creator gods within the macrocosm move in the design of one great archetype. This archetype describes “the rhythm of consciousness moving through the world. This rhythm is the motion of Tao, symbolized in China by the undulations of the body of a cosmic dragon.”

By attuning themself to the cosmic rhythm of the Tao, the meditating mystic experiences an alignment in consciousness between their own inner psychology and the divine spiritual archetypes existing in Space. Through this process, the mystic “recapitulates the divine creation process” and "experiences the very mystery of creation.”

The disciple of the Pythagorean school, meditating upon the design of the Tetractys, stimulates its cosmic principles within himself and thus recapitulates within his own microcosmic consciousness the same process of creation as that which originally took place within the macrocosm or universe as a whole.

Through this method, “Pythagoras revealed a kind of yoga, a means of disciplining human consciousness by reference to the orderly procedures of number, which represent the systematic unfoldment of creative processes moving out from their own causes.”

Hall elaborates on the mystical disciplines that the Pythagoreans incorporated within their school: “the Pythagorean philosophy of number was held to be both scientific and intuitive. Once the disciple had been instructed in the principles of the teachings, he advanced by a process of personal discovery. New mathematical patterns and equations continuously presented themselves to his attention. These he interpreted according to his own unfolding insight.”

As we’ve discussed, the performance of mediation works through the stimulation of archetypes. Once awakened, these archetypes “come alive”. The challenge of meditation is simply to awaken them and bring them to life within ourselves.

Manly Hall describes this act of awakening divine powers within as one of “reminiscence”: “To Pythagoras, mathematics was a science built upon reminiscence. By this he meant that mathematical principles were not discovered, created, or invented by the mind, but had an eternal subsistence in the intelligible nature of all things. Reminiscence, therefore, is a recalling of that which is already known, usually by a process of association. One thing reminds us of another, leading to a refreshment of recollection. That which is recollected is drawn into the fore part of attention, where it becomes available again after being seemingly forgotten.”

By catalyzing this process of “reminscence” within its students, the Pythagoreans sought to “draw certain deep and hidden knowledge from within the individual and apply it to the deep and hidden mystery of the world.” Therefore, by practicing the philosophical disciples emphasized by the Esoteric School, by degrees, the wise man could perfect the grand concept of existence and establish his own proper place in the universal program.”

The initiates of the Pythagorean school utilized the mandala of the Tetractys to instruct their disciples on these archetypal processes associated with the onset of First Cause. Later, in the more advanced degrees of the school, these concepts would be meditated upon and mystically experienced.

Hall informs us that, “as stated by Pythagoras, before any man might have any right to attempt to determine the nature of First Cause, he must first be sufficiently disciplined out of the common evils of the undisciplined mind.

In the Pythagorean school, the Tetractys served as the primary teaching device through which the student’s mind was brought into “discipline”. First, this mandala served as an instructional emblem that laid out core elements of the Pythagorean doctrine for the student to study and comprehend. Later, the student would meditate on the mandala in order to experience its truths directly during a mystical experience of illumination.

29. The Tetractys and the Four Worlds

There are numerous levels or layers of interpretation that one may go into while dissecting the symbolism of the Tetractys.

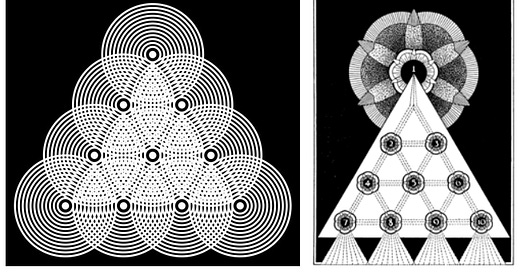

The diagram located at the heading of the previous section features one level of symbolic interpretation for this mandala. (It is taken from Manly Hall’s booklet “Superfaculties and Their Culture”). Here, we find the ten dots of the Tetractys juxtaposed next to ten numerals arranged in a triangular pattern, with the numeric principle of “0” at the apex, the numerals 1 and 2 below it, 3, 4, and 5, below that, and 6, 7, 8, and 9 arranged on the bottom.

Above we find a second diagram of the Tetractys, one that emphasizes a different symbolic pattern embedded within the symbol. In this second approach, the Tetractys's ten dots are divided into four levels or tiers, each named using the original Sanskrit word for the principle that each level represents.

At the apex of these four levels we find the principle of “Atman"; on the second level, we find “Adi"; on the third we find “Buddhi”; and onto fourth “Manas”. Together, these four principles represent the “Four Worlds” of ancient Indian spiritual cosmology.

Within and through these Four Worlds are distributed the nine numerals and the sacred “0”, which together serve as the foundation of our decimal system.

In this section we will be going one by one through the philosophical teachings of the Four Worlds and consider how they unfold and interrelate in order to form the four domains of First Principles out of which the material universe is created.

In the Tao the Ching, there is a famous passage that states

Tao gives birth to One

One gives birth to Two

Two gives birth to Three

Three gives birth to all created things.

In this section, we will be revealing how the ancient philosophical teachings of the Four Worlds offers a perfect explanation of this classic passage.

“Manas”, as the “Third Logos”, becomes the creator “of all things”. This power represents God’s capacity to form-build. The four dots next to this principle represent the four elements of the physical world, which are the four base materials through which this creating power labors.

Whereas “Manas” indicates the power of deity over the “lesser” forms of material creation, “Adi”, associated with the number One, represents the inverse: it indicates the “greater” world of Spirit, which plays host to division but is itself not divided.

In between the Greater and Lesser is the “Golden Mean” or divine intercessor, which is represented in Sanskrit by the word “Buddhi”. This principle represents the power of Divine Mind, which emerges within the Self in order to play host to the lower worlds of material creation.

The power of Manas is one of the three powers of Buddhi: it is responsible for building out and bringing into manifestation the various forms that comprise material creation. Its three attributes are creation, destruction, and preservation.

The three dots next to “Buddhi” indicate the three levels of the World Soul: a) one dot represents the spiritual world of heaven above where the archetypes reside; b) a second dot represents the material world of Earth where mortal lives are played out; and c) a third dot between them represents the intermediary world of Soul, Psyche, or Mind which serves as an intercessing agent between the two.

As we analyze the esoteric significance of these four principles (Atman, Adi, Buddhi, Manas), we will make reference to the initial diagram featured at this chapter’s header, and also to a supplementary diagram featured below (provided by Manly Hall from the same booklet referenced before).

a) Atman

Atman, the first level or world of the Four Worlds diagram, represents unified consciousness. In ancient Hindu religious philosophy, this principle is personified as Brahman.

While Brahman or Atman personifies the highest definable state of God, esoteric philosophy teaches that God is contained within a further state of existence: that which is “beyond Brahman” (or in Sanskrit, “Parabrahm”, with the prefix “para-“ meaning “beyond”).

In Helena Blavatsky’s words, the principle of Zero or “Parabrahm” describes “an omnipresent, eternal, boundless, and immutable principle on which all speculation is impossible, since it transcends the power of human conception. … It is devoid of attributes and is essentially without any relation to manifested, finite Being. Therefore, it is “Being-ness” rather than “a Being”.

Manly Hall expounds on this definition, describing the principle of “Parabrahm” as “the One Universal Life, impersonal and without dimension. It is the Absolute Source and Ultimate End of everything.”

Elsewhere he writes: “To define adequately the nature of the Absolute is impossible, for it is everything in its eternal, undivided, unconditioned state. In ancient writings it is referenced as the Nothing and the All.”

By contrast, Hall defines Atman as “the personification of Oneness or Parabrahm”. Here, “the Formless assumes the Divine Form; the One assumes the first veil of Maya.”

Diagrammatically, Parabrahm is symbolized by the empty circle, while Atman or Brahman can be symbolized as the emergence of the dot in the center of the circle.

The image that results symbolizes an eye: when Atman emerges, the eye is open; at the completion of a cycle of existence, when Atman or Brahman is reabsorbed back into Parabrahm, the eye closes and there is a “cosmic night of rest” until eventually it comes time for a new cycle of creation to once again commence.

With this placing of the dot in the circle, a triad of factors become constellated together: the dot, the circumference, and the radius. Synthesizing these three factors, the principle of Atman can also be symbolized as a Triangle, which is how we find it represented in the above diagram.

In Sanskrit the three principles contained within Atman are termed “Adi”, “Buddhi”, and “Manas”. In Hindu religious philosophy, they are termed “Brahma”, “Vishnu”, and “Shiva”.

In sum, Parabrahm and Atman both describe Unity, but in two relative states of each other.

Parabrahm is eternally outside of creative involvement, while Atman is the first point of contact between the Absolute and the lower worlds of manifest creation.

This point of contact takes place through the three persons of the Trinity. Each of these “persons” is involved in "stepping down” the consciousness of Atman so that it may enter into a limited and conditioned cycle of creative activity.

b) Adi

If Atman represents the outer face of Parabrahm manifesting in the form of a Triad of divine powers, then the next principle in our diagram, “Adi” (which means “one” or “first”) represents the first and highest principle featured in this Triad.

The first principle of this Trinity, “Adi”, represents the Godhead of Creation or “Spirit”. It is like Brahma, which emerges as the outer face of “Brahman” to become the Father principle of the Brahma-Vishnu-Shiva triad. Here, Adi is Brahma, Buddhi is Vishnu, and Manas is Shiva.

Adi, as Spirit, represents a portion of Infinite Being’s consciousness “set aside” to be focused into a cycle of Self-Experience. Hall elaborates, informing us that, in relation to Atman, Adi “occupies a position somewhat analogous to a focal point.” Here, “the unknowable potentialities of Absolute Existence are concentrated and, through the nature of Adi, passed downward and distributed within the negative sphere or field of manifestation as active potencies. Infinite Being (Atman) thus flows through God (Spirit; Adi) into manifestation.”

God emerges out of Absolute Being as “the first all-inclusive bubble, a magnificent iridescent sphere floating gracefully through eternity. Within its transparent shell, creation lives and moves and has its being. Its purpose finally fulfilled, the bubble bursts and disappears, its parts are reabsorbed into the surrounding apparent nothingness” of Parabrahm.

Referencing the above diagram of the Tetractys, the two dots next to “Adi” represents the onset of duality or polarity in the form of “Spirit and Matter”.

The concentrated area or “focal point” that the consciousness of Atman flows into is counterposed by a state of relative absence. This “void” represents Matter.

The lower two levels of the Pythagorean Triad take place within the concentrated region of Spirit and therefore each exists always in relation to this counterposing domain of Matter.

Matter is a necessary counterpart to Spirit; to designate the latter, one must necessarily also designate the former. It is only when all designations cease that the two reunite to become one.

In the language of Taoism, when Spirit arises as a focal point, it does so as an expression of the principle of “Yang”. This Yang principle is necessarily counterbalanced by a “Yin” principle, which becomes Matter.

c) Buddhi

The philosophic principle “Buddhi” represents the internal power of Soul or Mind that harnesses the power of Spirit or “Adi” and distributes it out into the field of creation.

In the circular diagram above, the principle of Buddhi is symbolized by a Cross. The horizontal portion of this cross represents the polarization between Spirit and Matter, with Spirit above the “Veil of Maya” and Matter below.

The vertical axis of the cross represents Buddhi’s extension across this Veil to unite the two polarities. The upper, superior aspect of this line connects to the sphere of Adi or Spirit, while the lower, inferior pole of this line extends into the world of matter and becomes involved with Manas, the form-building, “animus” power of the Soul.

Overall, Buddhi is an intermediary link binding together the dual realms of Spirit and Matter. It unites the duality into a Triad, bridging the superior, incorporeal realm of Spirit that exists above the veil of Maya with the lower, corporal realm of material form below it.

In the Tetractys diagram, the three dots next to the “Buddhi” principle are correlated with the triad of Pythagorean principles indicated by their famous 3-4-5 Triangle (which we discussed in depth in our earlier chapter on Pythagorean philosophy).

The Pythagorean principles of the Triad, Quaternary, and Pentad represent the three powers of the Soul: Consciousness, Mind, and Form. Often, these three powers are personified as a Divine Family: Father, Mother, Child.

These three inner powers of the Soul are an internal expression of the superior powers of Spirit that brought the Soul into existence in the first place. The Soul is born as the product of God the Father (Consciousness) “impregnating” God the Mother (Mind), which then gives birth to the Universal Form of material creation.

The three powers of the Soul are reflected into three levels of activity that take place with in it.

At the highest level is the “heaven realm” where the spiritual hierarchy resides. Here, the consciousness of Self is distributed throughout a hierarchy of divine beings and creative powers, who together work to distribute this consciousness throughout the lower realms of material creation.

In between the two realms - one subjective and spiritual, the other objective and material - is an intermediary realm, where the consciousness of Spirit is guided down to inhabit the bodies of material forms below. This intermediary realm is partitioned into seven levels, where the seven archetypal Soul Powers or Mind Powers are expressed.

Only once all seven powers are fully expressed will the Soul generate the capacity to build a perfect material form that can completely express the innate powers and potentials of the Spirit. It is the task of the principle of Buddhi to ultimately ensure the building of this perfect World Form.

d) Manas

The philosophic principle of “Manas” equates to “Shiva” in the classical mythology of the ancient Hindus. This principle is associated with the form-building power of the Soul.

Manas is not a separate power from Buddhi but rather is an internal capacity that Buddhi contains within itself. It represents the power of the Soul to create, preserve, and destroy material bodies or forms.

As Manly Hall explains, Spirit is the Father of the Universe, Buddhi is the Universe itself, while Manas “is the Organizer of the Universe: it brings order out of chaos, brings forth night and day, establishes the seasons and the things conveyed in the opening chapter of Genesis.”

In the circular diagram above, the power of Manas is represented by a square. And in the Tetractys diagram, it is associated with the four dots at the bottom or base level of the pyramid. In both cases, this quaternary design represents the four base elements from which Manas builds material forms: Air, Fire, Water, and Earth.

The four elements represent four distinct planes of matter that overlap. These four planes become the basis of the four bodies of the Soul: a mental body, an emotional body, a vital body, and a physical body.

The physical body, representing Earth, is a receptacle into which powers of the other three bodies are poured. These bodies exist in planes of matter that are “subtle” - meaning they are not located on the physical plane of matter but rather in three overlapping “metaphysical” dimensions that surround and envelope our physical dimension.

The power of Manas extends across all four planes of Matter and builds forms or bodies within in each dimension.

In sum, when we place the numeric principle of “0” at the apex position of the pyramid of the Tetractys, we find revealed the inner mysteries of First Cause.

The 0 represents the Unnamed One from whom all things come. All further numbers are the outpourings of this eternal principle.

The single dot opposite this Divine Atman bears witness to the One Life which is above and superior to all of the others.

The two dots by Adi remind us that Spirit is manifesting through two poles, positive and negative or Father and Mother. These become embodied as the superior world of Spirit and the inferior world of Matter.

The three dots opposite the principle of Buddhi give us the three phases of the soul or Mind Sphere. And finally, the Four dots opposite Manas represent the four elements of the Physical World: Air, Fire, Water, and Earth.

30. The Tetractys as a Mandala of the World Soul

As previously discussed, the Tetractys mandala lends itself to two levels of interpretation.

In the above sections, we analyzed the mandala in terms of its depiction of First Cause, where nine numerical principles emerge out of the abstract ultimate principle of “0” to collectively give birth to Creation, which symbolically becomes the number Ten.

Manly Hall explains that “Ten is the receptacle of the number One, for it gathers into itself the previous numbers, becoming a ‘second unity’, from which a new sequence emerges.”

This “second unity” is the World Soul, which the Pythagoreans often termed the “Monad” or “numerative soul”. This Soul is the vehicle of the Self during its cycle of creation and is what this second, alternative form of the Tetractys mandala depicts.

In other traditions, this World Soul is denominated ‘Atlas’. The Pythagoreans termed it the “Monad”, while the ancient Hindus called it “Ishwara”.

This World Soul “receives into itself all the previous numbers, unites them, and becomes a second unity. This, however, is a unity by effect and not by cause. It gives rise within itself to a new order of existence.”

Thus, in this second version of the Tetractys mandala, we find depicted “the Soul as a secondary power over creation. It is suspended from the archetype of number and falls through the numbers into generation.”

Thus, in Hindu philosophy, it is stated that "Brahma provides the principles, Ishwara the form.”

As in the Buddhist mandalas, the symbolism of the Tetractys diagram unfolds out of its apex principle. In both cases, this principle is the same: the Divine Self, which the Pythagoreans called the “Monad" and the Buddhists “Mahavairocana”.

To the Pythagoreans, “The ultimate source wisdom could cognize was the Monad.” As Hall explains, “in contemplating the Tetractys as a kind of mandala, the most solemn consideration must be given to the Monad (1). It is the parent of number, the progenitor of numbers, the eternal parent of generations, the source of life, and the perfect symbol of illumination. … As unity, it is the All; of numeration, it is the first; and as the end of all things, it is completion.”

Elsewhere Hall writes that "the God of Pythagoras was the Monad or the One that is Everything. He described God as the supreme Mind distributed throughout all parts of the Universe - the Cause of all things and the Power within all things.”

In this way, the Pythagorean principle of the “Monad" corresponds to "Mahavairocana Buddha”, who is the central Buddhist deity whose inner mental nature is described in the Diamond and Matrix mandalas.

In the two Buddhist mandalas analyzed in the previous article of this series, Mahavairocana is enthroned at the center of each, with the various levels of Buddhist deities surrounding him serving as the secondary attributes and powers of this single sovereign Being. The Tetractys works in the same way, except for one difference: the primary principle of the diagram - the Monad - is not located at the mandala’s center but rather at its apex point.

The Tetractys, as its pyramidal design descends from an apex point, symbolizes the Divine Self manifesting its consciousness through the World Soul, which is the internal vehicle that the Self uses to bring its own powers and potentials into a state of creative expression.

The ten dots of the Tetractys symbolize this archetypal quality of wholeness possessed by the World Soul. Thus, “the sacred number 10 symbolizes the sum of all parts and the completeness of all things.”

From the Tetractys’s apex, which is wholeness, it diverges to a base, which consists, hypothetically, of an infinity of fragmentary parts. These fragmentary parts are always contained within the wholeness of the Self.

Furthermore, within the Self, each fragmentary part exists as a miniature Monad - i.e. as a microcosm of the whole.

In ancient philosophy, we often find the story of the manifestation of the Self through the World Soul symbolized in agricultural terms.

As Manly Hall explains: “We begin by taking an acorn and planting it in Space. It grows and becomes a great tree, but the tree is only the expression of the germ of life that was in the acorn. Every leaf and branch of the tree was in the acorn; the process of growth merely manifested the powers of the germ by clothing those powers in substance borrowed from the earth about the seed. The spirit of the tree does not actually grow, but as its manifestations increase it builds an ever growing form to express them.”

He continues: “This tree reaches maturity and is itself covered with acorns, each the size of the original one. But all these seeds were also in the germ of the first acorn or they could not have come into form. Each of these also blossoms into a tree and these again are covered with their acorns, but even these distant seeds are found in the germ of the first acorn that was ever planted. Thus, division takes place within the germ, but the germ is never divided, for it is always the sum of all parts of itself.”

In her writings, philosopher and theosophist Annie Besant, an early peer of Manly Hall’s, discusses this dynamic of the Divine Self (the Monad) manifesting through the World Soul (the Tetractys) at length. In her book Ancient Wisdom she discusses this process in terms of the Hindu deity Ishwara, where she writes:

“The source from which a Universe proceeds is a manifested Divine Being. … Coming forth from the depths of the One Existence, Ishwara, the Divine Being, imposes on Himself a limit, circumscribing voluntarily the range of His own Being. In so doing, he becomes the manifested God.”

Within Ishwara’s self-circumscribed sphere of being, “the Universe is born, is evolved, and dies. It lives, it moves, and it has its Being in Him. Its matter is His emanation; its forces and energies are the currents of His Life. He is imminent in every atom, all-pervading, all-sustaining, all-evolving. He is everything and everything is in him.”

This Divine Self, working through the World Soul, is the one flame or light from which all subsequent fires are lit. Besant continues:

“Ishwara, in manifestation, is like a lamp, a light enclosed in a shade. Enveloped in Maya, He brings forth a universe and is enclosed in the Universe of which He is the Light.”

“(Ishwara) assumes this veil for the purpose of manifestation, using it for the self-imposed limit which makes activity possible. From this He elaborates the matter of His universe, being Himself its informing, guiding, and controlling life.”

31. The Tetractys and the Septenary

In its ten dot pyramidal design, the Tetractys reveals the esoteric teaching of the Seven Rays, something we covered in depth in our earlier series on Mahayana Buddhism.

These Rays represent the seven Mind-principles of the cosmic Self. Their emergence marks the onset of creation. Together, these Rays work to distribute the powers and qualities of the Self within the World Soul.

Manly Hall explains how this teachings is revealed in the Tetractys: “By connecting the ten dots of the Tetractys, nine triangles are formed. Six of these are involved in the forming of the cube. The same triangles, when lines are properly drawn between them, also reveal the six-pointed star with a dot in the center.”

“Only seven dots are used in forming the cube and the star. Qabbalistically, the three unused corner dots represent the threefold, invisible causative universe, while the seven dots involved in the cube and the star are the Elohim - the Spirits of the seven creative periods. The Sabbath, or seventh day, is the central dot.”

In other words, “the first three dots represent the threefold White Light, which is the Godhead containing potentially all sound and color. The remaining seven dots are the colors of the spectrum and the notes of the musical scale. These colors and tones are the active creative powers which, emanating from the First Cause, establish the universe.”

As the Tetractys demonstrates, these seven creative principles manifest their powers in the form of a Cube, which becomes the geometric symbol of the ensouled material body of creation.

The Seven Rays extend out into matter in the form a cube. This cube is formed as the consequence of Six principles projected out in opposite directions from a central seventh point. These six directions form the six faces of the cube.

The six directions are the motions of Number away from the center, which is the unmoved point of motion. This is the “Sabbath”, from which the Six Days Work proceed and back into which they culminate.

In his writings, Manly Hall often emphasizes the importance of the Septenary when analyzing the inner dynamics of the Soul. For example, referencing the Buddhist teaching about this Septenary, he writes:

“The Universe is composed simply of thoughts and is dependent for its existence on the directionalization of the wills of the seven Dhyani Buddhas. … (They are) seated upon their lotus thrones, where they remain forever in contemplation, deep in the eternal state of the principle which they personify. … Their Rays of Thought-Meditation are reflected into every atom of space and establish the inevitability of the septenary Law in nature.”

Elsewhere, he notes that this Septenary are “the Lords of the Mind” and together represent “the wholeness of the power of Mind that is oriented toward creation”. This septenary Mind is the “fashioner of the great World, the Abyss that came forth.”

In esoteric philosophy, the number Seven is associated with the idea of “Cosmic Law”. Together, the seven creator gods embody the Law by manifesting their energies in perfect accordance to it.

In philosophy, the septenary symbolizes Law, or more specifically, the “Will of Deity revealed through the workings of Law.”

In this way, the Septenary symbolizes the “celestial integration of processes which constitute the inevitable pattern of conduct for all things.” Therefore, “Seven is the number of the conduct of God”.

Another way of stating this is that “Divine Law exists archetypally within the Divine Being in the form of a Septenary.”

These seven creator gods who embody the Law perform their creative works “by circulating through their own nature the heavenly fire, which is the life of all things.” Describing the descent of this spirit fire though these seven creator gods, each representing one of the Divine Self’s seven inner “chakras”, Manly Hall writes:

“It is said that the Logos (the Self), when the time came to create the material universe, enters into a state of deep meditation, centralizing His thought power upon the seven flower-like centers of the seven worlds. Gradually, His life force descended from the brain (the superior world / heaven) and, stoking these flowers one after another, gave birth to the lower worlds. When at last His spirit fire struck the lowest center, the physical world was created and His base was at the world’s spine.”

Annie Besant elaborates on this creation process, noting that: “as the psychological energy of the Self descends deeper and deeper into matter, it draws together more and more separate forms. … At last it comes down to the mineral form, where life is most restricted in its operations, where consciousness is most limited in scope. … Then, from its nadir, at its lowest point, the life re-ascends, revealing and regaining more and more of its powers” in the process.

Hall then concludes: “it necessarily follows that the path of evolution for all things is to raise this spirit fire, whose initial descent made every manifestation in this world possible.”

32. Three Above, Four Below (the Rose and the Cross)

The Tetractys offers us a second way to analyze the inner dynamics of Soul’s septenary creative powers. If we consider the Tetractys once more as a diagram of the “Four Worlds”, we find that the top two levels, comprised of three dots, form an “All-Seeing Eye” overtop the pyramid base, which is comprised of the lower two levels and the seven dots they share between them.

These lower seven principles are themselves divided into two groups: one containing three powers (Buddhi) and the other four (Manas). “ The higher group - that of three - becomes the spiritual nature of the created universe; the lower group - that of four - manifests as the irrational sphere, or inferior world.”

Thus, Three is the number of the positive, spiritual pole of creation, while Four is the number of its lower, material aspect.

As we discussed in our previous series on Pythagorean philosophy, it is the function of the Triad (3) to bring equilibrium, balance, and reconciliation to the Quaternary (4). Hall explains: “As a mediating number, three binds up conflict and restores the balance of the universal process. It is a messianic number, and is associated with the power of the human consciousness to reconcile all opposites in nature.”

Overall, we can conclude from these teachings that, in creation, a primary Triad of divine principles (“Consciousness, Intelligence, Force”; ”Adi, Buddhi, Manas") synthesize to create a field of Self-Consciousness in which the Four elements of material creation are brought into manifestation in the effort of building and perfecting a World Form.

Once the World Form is ultimately perfected, the four base elements comprising it are transmuted back into the spiritual essence from which they were first derived - the fifth element “Ether”. Symbolically, this represents the Rose separating from the Cross, where the threefold Sattva principle exists independently of involvement with the four base elements of material form.

If one looks at the World Form as a grand, cosmic “Thought” produced by a single divine mind, then it makes sense that, when this thought comes to completion, the mind behind it would withdraw its projection of it “and the entire, massive, complex cosmos dies for want of it.”

Besant writes: “Finally, when Ishwara - whose Consciousness was the One Consciousness in the Universe, whose Life was the One Life, who supported every form, who made the possibility of every separated existence - gathers up His universe into Himself, when He merges Himself in the One, … nothing remains save the center of his Consciousness.”

She continues, writing that, after breaking through the veil of Matter or Maya that had previously enveloped him, His “Light shines forth in every direction. Dissolving the Universe, He still remains, but the circumference that circumscribed Him is gone. … He alone remains, holding His center unshaken in the very act of merging in and expanding into the Infinite, the Absolute, the Super-Consciousness, the One.”

In this eternal center “there remains the power of vibration. … Therefore, when Ishwara merges Himself in the One Existence, all else has vanished as form, but powers remain in those subtle modifications, preserved in that unchangeable center in the mightiness of the One Life.”

Here we find the idea that at the dissolution of the Universe, the initial seed of Being (Self) that initially created the Universe becomes preserved in the womb of existence, which it will eventually emerge back out from at the onset of a new cycle of existence.

Writing of the eventual reincarnation of this Divine Self, Besant writes: “When Ishwara arises in order that a new Universe may be formed, he throws His life into those meditations that had apparently disappeared. … From His own revivified memory, He draws His consciousness under the impulse of the Great Breath, and limits Himself again to Self-Consciousness, turning his attention to the contents of Himself. As he does this, His powers start into activity.”

This “memory-prompted desire of this Divine Boddhisattva is what arises in the bosom of the Eternal at the root of the next cycle of creation.” This desire becomes the seed that will germinate over the course of the next cycle, which the great Dhyani Buddha Mahavairocana, the eternal penitent, will once again project from his own consciousness as an act of cosmic meditation.