1. Introduction

This article begins a new mini-series of essays on Esoteric Philosophy. As with its previous counterparts, this series comes together to form a chapter in a larger book, titled “Philosophy: Its Origin, Purpose, and Destiny”.

This chapter is the 8th of 13 chapters that together make up this book. I’ve been sequentially publishing, in serialized form, each chapter of the book since March 2022. The first chapter began back in March with an article titled “The Mystery Schools and the Invisible Government”. At this point, in mid October, the book is now over half done, with six chapters having now followed the first.

In contrast to the early chapters of this book, which are one essay each, the past few chapters have been more detailed and have consequently been split up into multi-part series. This pattern holds true for the remainder of the book: each subsequent chapter is long and detailed and therefore will also be divided into multiple sections.

This book project is taking place as part of a larger ongoing multimedia project spread across this blog, a companion podcast (called “The Wisdom Tradition”), and an associated YouTube channel. (See my website www.alexsachon.com for links to everything.)

On my podcast and YouTube channel, I go back over and analyze each of the published articles, offering further commentary to the written material. In addition, on these platforms I also feature supplementary content that provides further context to the main articles. These include analyses of important Manly P. Hall lectures on topics relevant to the various subjects covered in the book.

Moving now onto the topic of this current chapter: its main focus is on “the philosophy of meditation”. Our coverage of this topic extends across five parts and will focus in depth on how special symbolic images termed “mandalas” were once utilized by the Mystery Schools in their occult meditation practices.

As we explore and unpack the esoteric science of meditation and, more specifically, the role that mandalas play in facilitating it, we will be drawing heavily on the philosophical and psychological concept of archetypes, which is an idea that we’ve already discussed frequently throughout this book.

The concept of archetypes references a domain of psychological and energetic activity rooted in a fundamentally collective (and not individual) sphere of human consciousness. The idea originally comes down to us from the Greek philosopher Plato and was later elaborated upon by Carl Jung, the godfather of Depth Psychology.

Although this is a topic we’ve touched on frequently in our previous articles, in this present series we will use the topics of meditation, mandala design, and the occult science of visualization as means to further explore the spiritual and psychological mystery of “archetypes”.

As part of this study of archetypes and their relationship to mandala symbolism, two case studies will be featured, one drawn from each of the previous two chapters of this book - Mahayana Buddhism and Pythagorean philosophy. These case studies will help advance our discussion of how these and other Esoteric Schools designed their curriculum around the use of mandalas.

As we will discuss, mandalas were used as meditation guides prepared for the benefit of disciples and initiates, who would study, reflect upon, and meditate upon these carefully designed symbolic devices.

In the two case studies we will be exploring, we will be comparing and contrasting how two important esoteric schools of the past - Mahayana Buddhism and Pythagorean Philosophy - utilized mandalas to convey their philosophical teachings to their students, who would contemplate and meditate upon them as part of their esoteric practices.

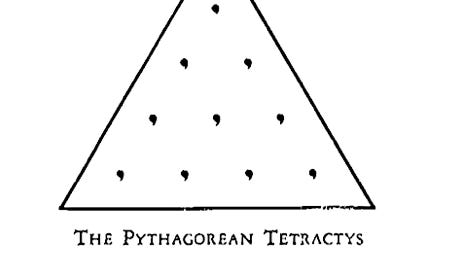

In relation to the Pythagorean sect, we will be investigating how they utilized a very simple mandala design called the “Tetractys” to convey important aspects of their esoteric teachings to their students and disciples. Within its surprisingly simple ten dot, triangular design are interwoven various numerical and geometric patterns of profound philosophical significance.

In our investigation into Mahayana Buddhism, we will be comparing and contrasting two important Mandalas used in their esoteric schools: the Matrix Mandala and the Diamond Mandala. Unlike the Tetractys, these two Mandalas are incredibly complex and involve a great amount of artistic detail. Nevertheless, behind all the complex detail and layers of symbolic imagery is conveyed a relatively simple set of archetypal themes and principles, ones which align in complete agreement with the simple numerical philosophy of their peers in the Pythagorean school.

Before moving on, one quick note: as has been the case for each of my articles, the content in this present series is heavily inspired by - and at times directly cited from - the work of Manly P. Hall, the great esoteric philosopher and sage of 20th century America.

Manly P. Hall is the expert on meditation and mysticism; in this series, I am merely synthesizing his (and other’s) teachings on the topic. Certainly, some of the input is my own, but the foundation of this upcoming discussion on the philosophy of meditation is not built around my own personal experiences with the topic but rather on my work as a scholar, researcher, and theorist on the history and fundamentals of Esoteric Philosophy.

On the topic of meditation and mysticism, I have some personal experience in this realm, but it is admittedly limited - especially in comparison to someone like Manly P. Hall. Therefore, I want to emphasize to the reader or listener that the information presented to you in this series is built upon a foundation of teachings derived from esteemed sources like Mr. Hall, rather than from my own expertise as a practicing mystic.

2. The Philosophy of Meditation

In the West what we typically call prayer is practiced in the East as an exact science called “meditation”.

Western religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam) have largely lost track of prayer’s connection to mysticism, but this link has always remained present just below the surface of Eastern religion (Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism).

The loss of its connection to a mystical core is the great tragedy of Western Civilization, as it is the key ingredient necessary to overcome the deep rooted attachments to theological dogma and political mismanagement that has plagued the West’s growth and evolution over the past two millennia.

Countering the dogmatism of our modern religious institutions, mysticism emphasizes the fundamental truth that each person, regardless of faith or creed, possesses a unique, personal connection to God. This personal connection is direct; one is dependent upon no other person, organization, or institution to connect with it and draw upon it.

Philosophy approaches religion psychologically. In its view, religion is treated not as the worship of God but rather as the experience of God. This experience must be earned, which is why philosophy advocates each individual to adopt a highly disciplined way of life, one specially designed to unfold and release an innate potential of God-knowing within themselves.

In this way, philosophy looks at religion as being fundamentally about a personal relationship with God, one that is destined to one day become actualized in the form of an intimate experience of Self-realization. The disciplines of philosophy are all designed to catalyze the unfoldment of this experience, which takes place gradually over the course of a series of levels, grades, or degrees.

This is where meditation comes in: meditation is an advanced form of prayer that, when practiced according to exact standards, rewards the faith of the dedicated individual by granting them an internal experience of enlightened Self-Consciousness. Here, in this culminating experience of the religious seeker, one experiences the actualization of their faith through “the transformation or transmutation of a devoutly held idea into an actually experienced fact.”

All mystical religions, such as those still found in the East, emphasize that the ideal of religion is to have one’s faith rewarded through the attainment of a mystical experience of universal consciousness.

As Manly P. Hall explains, “the practice of the mystical disciplines must result ultimately in the attainment of the mystical state. (In this profound spiritual experience), a strange enthusiasm rises up and fills the consciousness of the mystic and he is obsessed by a powerful ecstatic emotion of exaltation or rapture. While thus transported he feels himself one with God and a part of all that lives.”

“In the mystical experience, man suddenly becomes aware of the totality of life. … This is an experience in which man realizes his total dependency upon a Greater Life and at the same time realizes his immortality within that life.”

In several of his writings and lectures, Manly Hall describes the ecstatic experience of mystical self-realization with beautiful poetic imagery; certainly, he is one who has known it. For example, in one passage he writes that in the mystical experience:

“There is an incredible burst of Light, as though a psychic atom has been split. … Physical forms disappear, boundaries of time and space fade away, and all that is seen is the radiance of causation on its various levels of being.”

This is an experience “above and beyond anything we can imagine.” In this experience, “the Power that administers the clouded world normally seen by the limited sensory perceptions suddenly reveals the mystery of itself; the psychic mechanism is revealed in its fullest splendor.”

With this revelation, one experiences the truth that “as in a lantern, every existing creature is a form enclosing a light”. The true dimensions of the cosmos are thus revealed: “every flower in the field becomes a radiant light. Even the physical Earth is vibrant with an eternal energy. Instead of a star-lit heaven, there is a star-lit Earth.”

The attainment of this experience of spiritual awakening represents a pivot point in the evolutionary development of the soul. After it occurs, one can never be the same as they once were. As Manly Hall explains, after this experience “the individual suddenly changes his point of view and takes refuge in the Law.”

Simply put, the authentic mystical experience is the true source of man’s religion. Religion is therefore primarily psychological and not institutional: it is about a personal connection with God, not fealty to a set of dogmatic ideas, scriptures, or institutions.

The goal of describing, cataloguing, and catalyzing the mystical experience was approached by the ancient Esoteric Schools as an exact science. Based on the conclusions of this inward spiritual research, the original esoteric disciplines of meditation, yoga, and alchemy were developed.

Mysticism is not only the basis of religion; it is also the basis of philosophy: the institution of philosophy was conceived and born by individuals - Pythagoras, Gautama Buddha, Lao Tzu, etc. - who were all initiates of the Mystery Schools of their time and place.

Each of the great schools of philosophy that first emerged during the Axial Age (~600 BC) derived their respective doctrines of philosophical and metaphysical teachings around a body of pre-existing esoteric knowledge that had been accumulated and passed down within the Mystery Schools, which each philosophical “founding father”, from Pythagoras to Gautama Buddha, was an initiate of.

The knowledge these teachers were granted in these Esoteric Schools was not purely intellectual; it was also mystical. The Great World Teachers of this period were all initiates, which means that each had undergone, as part of their initiation, a mystical experience of “spiritual rebirth”. The knowledge departed to them during this experience would have directly inspired them to teach the doctrines and found the academies that they would later gain renown for.

Being products of the Mysteries, each of these great teachers recapitulated the basic pattern of the Esoteric Schools within their own philosophic academies or “sanghas”.

For example, each of these ancient philosophic schools, without exception, contained within its innermost structure an esoteric body where occult meditational practices and rituals were developed and practiced according to an exact science.

This repeats the pattern of the Mysteries, where the “outer body” would practice the “lesser rites” involves with preparation and purification, while a smaller “inner body” practiced the “greater rites”, which involved mystical and meditational exploration of the metaphysical dimensions of Spirit.

Also like the Mysteries, the existence of this inner, esoteric body within these philosophic schools was largely concealed from the awareness of those in the outer body. Today, most don’t realize that each school of philosophy, from Buddhism, to Platonism and Pythagoreanism, to Taoism, has both an “exoteric” and “esoteric” aspect, the former corresponding to a “public” body of teachings for the masses and the latter to an inner, mystic doctrine for the more advanced and accomplished students.

In the case of Plato, our previous article on the philosophy of the Golden Ratio provides documented evidence that his outer teachings contained deliberate cypher-like elements that allude to the fact that he also had developed and was teaching a higher, esoteric doctrine to his most advanced students.

In the sections to come in this chapter, we will explore in detail the fundamentals of how these Esoteric Schools designed and carried out their advanced meditational practices.

As part of this discussion, we will take a particular focus on how these mystic fraternities utilized methods and techniques such as mandalas, mudras, and mantras as part of their meditation disciplines.

In later sections, we will consider two case studies of mandalas used by esoteric branches of two important philosophic schools: the Pythagoreans and the Mahayana Buddhists. These case studies help to emphasize the main ideas and themes being discussed in this chapter’s initial sections, while also revealing further details about the meditational methods and techniques used by these two philosophical schools.

3. The Psychology of Meditation

Esoteric philosophy’s approach to meditation is premised upon the innate relationship that exists in the human psyche between the dueling principles of Self and ego.

The aim of meditation is to stimulate a mystical spiritual experience within the psyche of the individual. The basis of this experience is the creation of a bond in consciousness between the two dominant principles of the psyche: an individual, body-facing principle called “ego” and a collective, spirit-facing principle termed “Self".

In the mystical experience, the individual psyche, rooted in the ego, opens up and becomes receptive to the greater encompassing consciousness of a higher Self (or “Super-Ego”). The receptivity is experienced as illumination, and the bond that is forged as a result is the basis of enlightenment.

During the mystical experience, the principle of the Self, which is divine in origin and exists in a universal state of awareness, rushes into the psychic field of the individual and illuminates its mental, emotional, and physical functions, synthesizing them together into a transcendent experience of “all-ness”.

This is the experience of spiritual awakening that all initiates of the ancient Mysteries once underwent. To undergo it is to be “twice-born”.

It was through this experience that one’s destiny and purpose in relation to the Divine Plan is first revealed. As Manly Hall tells us, “when the personal ego attains a condition of rapport with the Super-Ego, it receives a larger vision and certain valuable instructions.”

At root of this explanation of mysticism is the idea that the soul or psyche of each human is polarized between two diametrically opposed states: one individual, the other collective. The former is the domain of the ego, while the latter is the domain of the Self.

Within the psyche, one experiences the principle of ego as the point of personal awareness or “I-am-ness” that one’s consciousness is directed toward at any given moment.

Wherever one’s point of attention is at a given moment in time, one’s “ego-consciousness” is there, orienting the in-streaming consciousness of the Self toward it.

In short, the ego is the psyche’s center of conscious awareness in the body. Its primary function is to, like an antenna, “tune into” the consciousness of the higher Self and draw it down toward an experience of embodied selfhood.

Unlike the ego, which is oriented toward the individual body, the principle of Self is, at root, universal and collective in nature.

There are many selves, but only one Self. The ego, which is the negative polarity of the Self within the psyche, draws the consciousness of the Self down toward the body. Through this mechanism, that which innately collective (the Self) is drawn into an experience of individuality.

The root of each persons’s experience of individuality is this principle of Self (in Sanskrit: Sattva), which resides at the apex of each persons’ psyche. In truth, this Self does not exist as an isolated spiritual entity, however. Rather, it exists as a spiritual cell contained within the being of a greater spiritual organism, the Vajrasattva or Divine Self.

The Sattva principle therefore signifies an aspect of divinity that resides in each of us. As such, the Self is, for each of us, the psychological gateway to a universal state of consciousness, one associated with the oversouling presence of single Divine Self (in Sanskrit: Vajrasattva).

Each human experiences within their psyche this archetypal principle of Self (Sattva) as a unique and highly personal power of consciousness exclusive to them and their life history. This is not the truth, however.

To quote Manly Hall: “mankind may be considered as a vast organism with one Spirit or Self manifesting through an infinite number of intellectual and physical organisms, the latter deluded into the belief that they are free and independent.”

As long as our consciousness remains directed predominantly outward toward the world of material forms and bodies, everything seems separate and different from one another. From this perspective, each person’s mind and consciousness appear unique and isolated from each other. However, once one begins directing their consciousness inward and encounters the true nature of their inner Self, this belief in the reality of diversity is quickly annihilated.

Once the archetype of the Self is directly confronted and beheld in its totality during the mystical experience, one discovers that, in actuality, this principle is not personal at all but instead is universal in nature, encompassing all people and life forms here on Earth and beyond.

By implication, each individual’s personal experience of selfhood is but one small part of a single, grand, overarching experience of Self-consciousness that is taking place within and through the entirety of Creation.

The psychological truth of human life is simple: all individual Sattva principles are derived from one overarching Vajrasattva.

This Divine Self is the single source of all individual experiences of Self-consciousness taking place here on Earth.

In Jungian terms, each person engages with this principle of Self within their own psyche through its presence as the “master archetype” enthroned at the apex of their unconscious. Once awakened, this principle of Self opens the door to the experience of a greater world of wholeness - that of the Universal Self.

For each human soul, their own Sattva principle is simultaneously the entry point out of and gateway back into the source consciousness of the Divine Self.

As Manly Hall explains, “the God of every man is not in the heavens nor in the immeasurable vistas of Space. … (Rather,) Man’s God is his own divine part, which resides in the remoteness of his own auric bodies.”

It is from this Sattva or Self principle “that each has his beginning; it is in it that each lives and moves and has his being during the period of his manifestation; and it is back to it that each returns again in the end.”

4. The Self, Reincarnation, and Prayer

As explored above, the meditation disciplines of esoteric philosophy are based upon the inner psychic relationship that exists between the dueling principles of ego and Self.

Within the psyche, the relationship between the Self and the ego is intended to be one of Teacher and disciple. Here, the Self principle of this equation is understood as a spiritual entity whose life extends beyond the incarnation of a single human personality.

This Self principle is a spiritual seed of the divine life; its history extends back hundreds of lifetimes. In each lifetime, the Self extends itself into the psyche of a human by channeling its consciousness through the mechanism of the ego principle. In this manner, it moves into and takes control over an individual human organism.

As Manly Hall explains: “among the potentialities of the Self is the power of projecting a host of individualities into temporary existence. After existing their appointed span, these individualities are reabsorbed back into the Self from whose essences they were originally differentiated. Thus the Self gives birth to an infinite number of personalities, but it is the Self - not the personalities - that endures. This Self does not actually incarnate or reincarnate, but from itself individualizes incarnating organisms.”

In philosophy, each person's connection to their own inner principle of Self is understood as being equivalent to their own inner experience of God. In both cases, what is being experienced is the same phenomena: the Sattva principle awakening within the psyche and uniting with the greater Vajrasattva that contains it.

Here we find God existing in a hierarchy of states, the closest and most personal of which is through the inner principle of Self. This Self resides at the foundation of our psyches, where it presides over and instructs, from “on high” the lower bodily nature of the individual.

By implication, the closest relationship that each person has to God is through their own inner principle of Self. Meaning: the Self is the Spirit of each human.

This Self remains outside the realm of corporeal limitation throughout the entirety of the cycle of creation, where, from its own state of detachment, it “broods over the incarnating part” and “contemplates the attachments which involve the inferior self.”

This view of the special role that the Self plays over each individual human life forms the backbone of Esoteric Philosophy’s approach to prayer and meditation.

In philosophy, the entire act of prayer is reframed: instead of praying to “mysterious gods abiding in remote parts of space”, our prayers are “actually addressed to this higher part of our own natures”.

Hall teaches us that, “every man’s true teacher is his own Higher Self, and when one’s life is brought under the control of reason, this higher Self is released from bondage to appetites and impulses and becomes priest, sage, and illuminator” to the lower bodily organism.

The disciplines of philosophy are designed to re-establish the archetypal pattern of authority that is supposed to exist between the Self and the ego, with the Self positioned as the spiritual authority or guru and the ego as the pupil following the Self’s instruction.

In esoteric philosophy, this Sattva principle within ourselves is sometimes termed the “immortal mortal”: it is mortal compared to God, but immortal in respect to each of the successive personalities that it extends from itself.

The Self is the true evolving entity of human life; the evolution shown by the physical personality is merely a material projection of a more fundamental set of transformations that are occurring within the chemistry of the spiritual soul.

The underlying truth is that behind each human lifespan is an inner, divine principle of Self - a “Super-Ego” - evolving through it. This greater Self is undergoing its own inner process of growth, moving ultimately from ignorance to wisdom.

The means by which the Sattva or Self accomplishes this evolution is via a successive chain of evolving personalities, which it extends from itself. These personalities are vehicles that the Self utilizes to catalyze its own superior evolutionary transformation.

As Manly Hall describes, “like each of its extensions, the Self is born, passes through childhood, attains maturity and age, and is finally dissolved in the Mahaparanirvana” (meaning the ultimate completion of the cosmic cycle).

Therefore, “like its personalities, it is within the world illusion. It has to also gain its own liberation through fulfilling the “Cycle of Necessity” and exhaust its instinct to objectivity, which it releases through the forms it fashions.”

The relative maturity of each human being is a reflection of the state of development of their own inner Sattva or Self principle.

The archetypal evolutionary end-state for each human is for their Sattva principle to mature itself to the point where it becomes the Bodhisattva, wherein its conscious awareness is opened and flows in resonance with the divine Life, Light, and Love of the Universal Self.

The awakening that the Bodhisattva goes through is truly transformational. Through it, one becomes reborn as member of the spiritual hierarchy or “divine government” of the world. As such, Bodhisattvas become intercessors between heaven and earth and in so doing join the Gods and demigods in forming the greater spiritual hierarchy of causation that overshadows, governs, and guides our lesser material sphere.

5. The Rose and the Cross

The meditating mystic interfaces with Universal Consciousness through the principle of “Self” or “Sattva” existing within them.

Counter to how some may imagine it, the Sattva or “Self” principle within the psyche is located not at a point but rather at the circumference or periphery of the psyche, serving as its container.

Within the circumference of the Self, all of the various functions and levels of psychic activity are contained. These include the four primary functions of the psyche (intuition, sensation, thought, and feeling) and the two opposing light and dark realms of conscious and unconscious.

As we will be covering further on in this chapter, in esoteric philosophy, the inner anatomy of the psyche is archetypally partitioned into a spectrum of seven principles, with the higher three principles of this septenary synthesizing to form the soul’s higher spiritual nature and the four lower principles combing to form its lower material nature.

The quaternary at the base of this soul pyramid is associated with the four base elements of alchemy (air, fire, water, earth).

In psychology, it is also associated with the four primary functions of the psyche (intuition, sensation, thinking, and feeling) and the four primary domains of psychic activity (the conscious and unconscious domains and the individual and collective domains).

While the threefold upper region of the psyche is home to the Self, the lower fourfold region is home to the ego.

While the ego is the basis of our day-to-day and moment-to-moment mental experiences of life, this principle is not actually a permanent being. Rather, it is a dynamic, ever-moving complex of attention and self-awareness that is constantly oscillating its focus between the psyche’s mental, emotional, and physical aspects.

The ego is not aware of all activity happening across all four lower psychic functions at once. Rather, its point of focus is forever oscillating between each as it constantly moves its attention from one concern to another.

At any given moment, the ego can only focus its awareness on a limited amount of psychological phenomenon; the fullness of one’s inner psychic life is not available to it. Therefore, the Ego is by definition never fully aware of the complete extent of the psychic factors moving into and affecting it. Only the Self is privileged to the full extent of this knowledge.

Here is stated the ultimate purpose of meditation: to release the higher aspect of the soul (3) from its bondage to materiality (4). This ultimately involves bringing the ego under self-discipline so that the Self or Sattva principle may be illumined and crowned as the psyche’s true sovereign ruler, which is its divinely appointed function.

As Manly Hall explains, “the visible human form is but the encasing vehicle for an invisible spiritual organism which is, in reality, the conscious individual.” It is to this invisible spiritual organism that the disciplines of meditation are dedicated.

Hall continues: “The conscious dedication of the physical personality to the needs of this superior Self results ultimately in union of the mortal personality with the Super-Ego. Through study and the unfoldment of interior powers of knowledge, man becomes aware of this radiant psychic entity from which his personality is suspended.” Therefore, “through understanding, man builds bridges of awareness by which his human personality becomes more perfectly adjusted to the Super-Ego.”

Delving further into the esoteric significance of this Super-Ego or Sattva principle, we may note that the Buddhist term Bodhisattva is a compound word comprised of two Sanskrit root words: Bodhi and Sattva.

Bodhi is a term describing the plane of Universal Mind associated with the consciousness of the Divine Self (think: Buddha-consciousness).

The word Sattva, meanwhile, represents the principle of Self that exists within each person. This principle is the divine element within each of us; as such, it is the gateway to higher levels of consciousness beyond our own.

Putting these two root words together, we find that a Bodhisattva is an individual whose consciousness principle (Sattva) resides on a plane of the Universal Mind where it is continuously awakened to the superior consciousness of a greater spiritual authority: the Divine Self (Vajrasattva).

In this light, the Bodhisattva concept, prominent throughout Buddhist religious philosophy, is understood as having a very specific meaning: it references a human who has attained conscious union with their “higher Self”.

This union of the “greater” and the “lesser” brings enlightenment. Therefore, the word “Bodhisattva” means “enlightened Self”.

For this reason, the Bodhisattva is defined in philosophy as a completely mature human being, where the Super-Ego or Sattva principle within them has taken full control over the lower psychic nature of the personality while, at the same time, retaining full awareness of its own continuity of life between and through successive lifetimes.

In this way, the Bodhisattva represents an ideal human: man at its most evolved state.

The Buddhists believed that it is the ultimate destiny of all persons to awaken and release this inner Bodhisattva within, so that we may one day perform the same service to others that a host of incarnating Bodhisattvas from previous cycles are performing for us today.

For the philosopher, this task of bringing the psyche into its ideal state of Bodhisattva-hood is one of learning to balance the four lower functions of the psyche together so that the ego may come to rest in their center. At the center, it establishes a bond of resonance with the triadic spiritual principle at the heart of the soul (the Self), and becomes permanently linked to it and placed under its authority.

This grand psychological transformation, balancing the higher spiritual nature of the soul with its lower material counterpart, is the “Great Alchemical Work” of the ages. It was symbolized by the Rosicrucians (a sect of mystic Christianity) as the art of separating “the Rose from the Cross”, meaning the higher spiritual nature (the Rose) from the quaternary division of the lower material body (the Cross).

Manly Hall describes this same viewpoint from the perspective of a different sect: the Pythagoreans: “Pythagoras believed that ultimately man would reach a state where he would cast off his gross nature and function in a body of spiritualized Ether. From this he would ascend into the realm of the immortals, where by divine birthright he belonged.”

Man at this level, existing in a body of spiritualized Ether, becomes what the Buddhists termed the Terrestrial Bodhisattva - the enlightened sage whose consciousness is no longer confined to the desires, attachments, and constraints of the material body. The Greeks termed this rare and outstanding individual the “World Hero”.

At this level, one lives and experiences the truth that “the soul of man is essentially a spiritual thing. Its true home is in the higher worlds where, free from the bondage of material form and material concepts, it is said to be truly alive and truly self-expressive. The physical nature of man, according to this doctrine, is a tomb, a quagmire, a false and impermanent thing; the source of all sorrow and suffering. … Birth into the physical world was death in the fullest sense of the word, and the only true birth was that of the spiritual soul of man rising out of the womb of his own fleshy nature.”

So many gems. Here's just two of my favorite:

"Western religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam) have largely lost track of prayer’s connection to mysticism, but this link has always remained present just below the surface of Eastern religion (Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism)."

"For the philosopher, this task of bringing the psyche into its ideal state of Bodhisattva-hood is one of learning to balance the four lower functions of the psyche together so that the ego may come to rest in their center. At the center, it establishes a bond of resonance with the triadic spiritual principle at the heart of the soul (the Self), and becomes permanently linked to it and placed under its authority."

Discipline is key to so many things. I could go on from the analysis you made on the Self and the Ego and so forth, but man -- beautiful work.

🙌🏼🙏🏼🫶🏼 much appreciation for all of your posts, Sacha!