Technocracy vs. Capitalism | Two Competing Economic Models

Part 3 of a series on Technocracy, extracted from my book THE COMING WORLD NATION

In the newest episode of my podcast, I continue my ongoing series on Technocracy, which is extracted from my recent book THE COMING WORLD NATION.

The focus of today’s discussion is on comparing and contrasting the economic visions of capitalism and technocracy. In particular, I argue that capitalism and democracy are products of the pre-industrial and pre-scientific ages and thus require fundamental reforms before they can integrate science and technology optimally. The result of these reforms brings us to technocracy, which aims for a scientific and energy-based approach to resource allocation.

Key topics in this discussion include: the inherent inefficiencies of current economic models; the inherent shortcomings of bureaucracies; how technocracy emerges as an innovation to both; and how the true vision for technocracy can’t be achieved until the classified science held within America’s black projects underworld is released.

00:00 Introduction and Overview

02:36 The Emergence of Technocracy

06:34 Technocracy’s Unique Economic Approach

11:45 Technocracy vs. Bureaucracy

20:24 The Future of Governance

Summary of My Comparison Between Technocracy and Capitalism

In this episode, I look specifically at the differences between capitalism and technocracy, comparing the two and show how the full expression of the modern scientific age can’t really come until we have a form of government that applies the principles of science as a primary function.

The current republics of the West are really the products of the pre-industrial and pre-scientific age. And the system of capitalism that we have - financial capitalism - is likewise the product of an earlier age. Science and technology, as they’ve been developing throughout the 20th century and now into the 21st century, have interacted with and put pressure on traditional governance institutions such as capitalism and democracy. This tension has never been totally been resolved. As a consequence, instead of science and technology moving into government in a productive way, they have become centralized under the control of a global cartel system ruled by an elite oligarchical caste. This oligarchy and the military-industrial complex that orbits around it leverages its control of science and technology to exert its power over the democratic institutions and to corrupt and pervert the republic in the pursuit of imperial domination.

The question now confronting us is: how do we have a science that actually has a productive relationship with government and that is targeted towards the betterment and optimization of the people, society, and the economy as a whole? The only way to achieve this is to fundamentally change, reform, modernize, and revolutionize the system of government that we have. Elements from capitalism and democracy can be included in the new system that results, but this system also has to have the potentials of science and technology hardwired explicitly into it. It additionally must be responsive to the ethical and moral challenges that science and technology confront mankind with - something our current governance system has been unable to do.

All these issues are informing the foundational shift from capitalism to technocracy that is now taking place. Technocracy is a new reality that every nation - and the “International Rules-Based Order” as a whole - must reckon with.

What Makes My Analysis of Technocracy Different from that of Other Scholars

My analysis of technocracy is a lot different than other analyses of technocracy that you’ll find because I’m factoring in big-picture philosophical and sociological issues that they don’t consider. One major difference between me and the typical analyst of Technocracy is that they assume this motion is, by default, a negative thing. And I look at it more as an archetypal development, which can have a negative or a positive quality of expression depending on the quality of the leadership orchestrating the movement.

Overall, I see the emergence of technocracy as an inevitable trend in the long-term evolutionary development of civilization. So rather than resisting it flatly or labeling it innately evil, I think we have to understand this development in a deeper and richer way. And we also have to take into account the myriad circumstances and motions that are pulling us in that direction. It’s not just a conspiracy of the elite to install technocracy; it’s really a motion taking place within the collective life of the race.

The current ruling elite are thus far driving this motion in a negative direction (i.e. toward transhumanism or digital serfdom) because that’s a representation and forward projection of what their psychology is anyway. It’s merely a translocation of the ethos that they’ve already hard-wired into the system of financial capitalism that we currently have. So it’s no surprise that they would want to port their ideology over into this new system, with the vision of the WEF’s Great Reset being a personification of this phenomenon.

But I think that we can contemplate a further horizon for technocracy beyond this. There could be positive consequences of this change, but in order to factor those in, we have to consider the possibility that what we most people consider science is actually confined to a paradigm called “scientific materialism,” which is based on a closed-system concept of physics. Most people don’t realize that there is an opposing paradigm of science, which has long-since been classified and which is based on the alchemical principles of the “luminiferous Ether.” The revelation of this long-secreted, open-system paradigm of science and technology will transform how we understand and think about technocracy. A totally different vision of technocracy becomes possible, one unrestrained by the secular materialistic ideology that now permeates the technocracy movement.

In this way, I see the current rollout of the Great Reset as only stage one of a larger process, which will be followed by subsequent new stages that current critics of technocracy have not yet begun to grapple with.

Technocracy’s Unique Approach to Economics

W. King Hubbert, one of the original pioneers of the Technocracy Movement, defined its approach to government in simple and straightforward terms: it is “the science of social engineering.” Through technocracy, “for the first time in human history, (government) will be done as a scientific, technical, engineering problem.” Patrick Wood, a contemporary researcher focusing on the history of technocracy, emphasizes that it “proposed a completely different economic system (than any) that had never been implemented in the history of the world. It was to be a system run by scientists and engineers, who would make decisions based on their application of the Scientific Method to control both social and economic matters.”

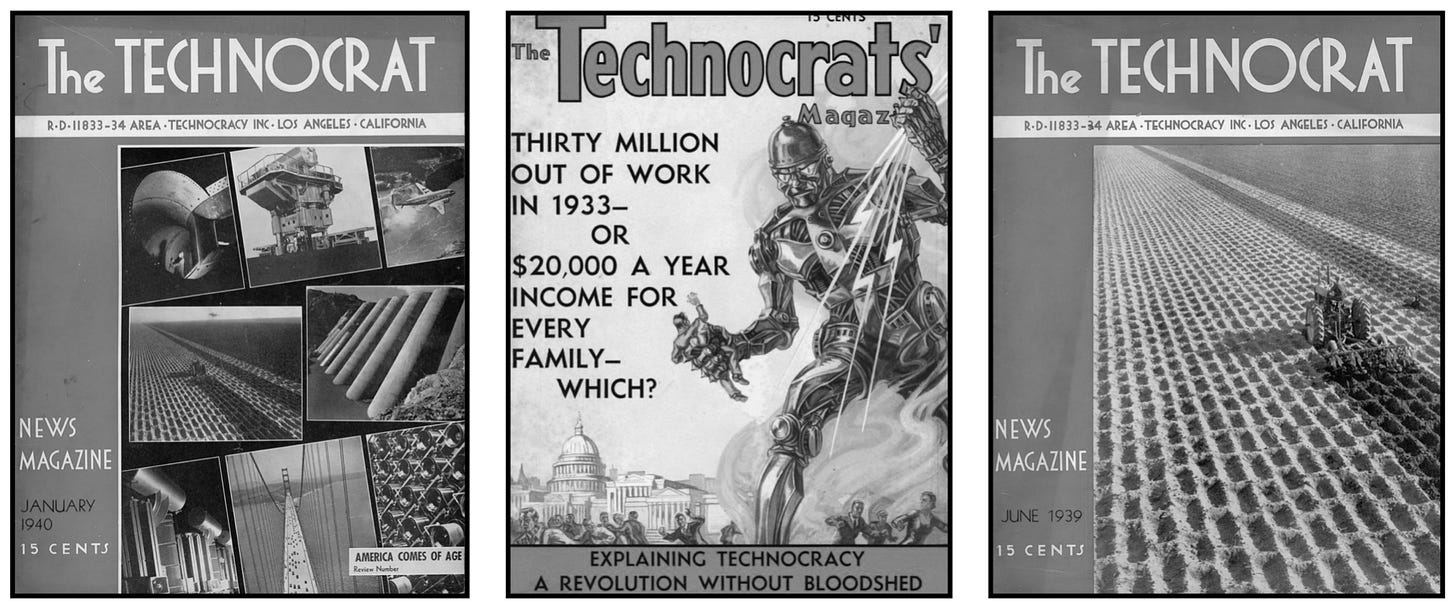

Hubbert and his colleague Howard Scott conceptualized technocracy as a replacement for capitalism, whose failures were made glaringly evident by the Great Depression of the early 1930s. Seeking an alternative to capitalism’s reliance on money, markets, and price, technocracy instead proposed a rational, science-based approach to resource allocation based around energy.

In this new model, the economy would be centrally managed by an elite network of scientists and engineers, who would use advanced scientific techniques and technological instruments to optimize how energy and resources are generated, distributed, and consumed within society. For this system to function, a steady stream of data about the production, distribution, and consumption of energy must be gathered and fed into a central scientific database, where it can then be analyzed and modeled. Policies, directives, and regulations are then formulated by a central think tank and implemented by the outer spokes of the technocratic hierarchy.

Elaborating on technocracy’s unique economic approach, F. William Engdahl writes how in technocracy a central scientific authority measures and “models ever-greater sectors of the economy” using “increasingly sophisticated econometric tools.” The purpose is to “describe and map the global economy and its total energy requirements well into the future.” While other social, cultural, and political goals may be incorporated into the formula, the root of the system’s design is in energy.

In Hubbert and Scott’s framework of technocracy, money is replaced by “energy certificates,” which are measured in units like joules or calories. These are exchanged to “pay” for goods and services, which in turn are “priced” using a complex energy-centered methodology that a central think tank designates (replacing the current hegemony of central banks). These energy certificates would be distributed across society based on the total available supply of energy and the degree to which each person, family, and organization has been calculated to contribute to the optimization of its flow.

By tying economic exchange to energy (joules, calories), the system would in theory eliminate inefficiencies and focus on sustainable consumption rather than profit-driven scarcity. Since “money” in this model is simply an allocation of available energy, allocated by a scientific governing body rather than a traditional central bank, it removes financial speculation, inflation, and debt-based economic growth as possibilities.

While market economies rely on price discovery through supply and demand, in technocracy prices are established through the scientific analysis of energy flow. This is performed by a central think tank, which implements a comprehensive data-gathering operation to gather the scientific information it needs to engineer the technocratic system. It alone is granted full access to the complete spectrum of data about the operations of the technocracy and consequently it is the only entity empowered to make alterations to the system’s design.

This rule-by-experts approach is vastly different from our present democratic and capitalistic models of governance, which tend to misallocate decision-making to those who are the most wealthy or powerful but not necessarily the most knowledgable or intelligent. Technocracy avoids this by delegating decision-making authority according to a strict scientific and technical rationale. This does away with traditional political and economic power structures, replacing them with a different kind of hierarchy that is scientific and technological in nature.

Overall, technocracy seeks to optimize economic efficiency by tying resource allocation to the flow of energy within the society. Instead of a central bank manipulating economic activity through interest rates, a central think tank balances its scales using scientific techniques. Not only does technocracy represent a radical new alternative to traditional models of government such as capitalism, democracy, socialism, fascism, and communism, it also transforms the way bureaucracies function, which is significant because every form of government mentioned above relies on bureaucracy. In fact, every form of government is really just a different way of managing and directing large bureaucratic systems, which are inherent to the existence of large states.

Bureaucracy is the traditional form of government administration. Its history traces back thousands of years to the early states of Mesopotamia, China, and Egypt. Bureaucracies are characterized by a well-defined hierarchy of authority, strict adherence to procedures and rules, and a clear division of responsibilities amongst departments and employees. They are also typically known for their stability, predictability, and adherence to law, which makes them ideal for routine government functions like tax collection, agricultural regulation, organizing large-scale building projects, and maintaining military forces.

Bureaucracies are often plagued with inefficiencies, political infighting, and resistance to innovation. This is why they typically work best in stable, slow-changing social environments like those found in ancient agrarian economies. By contrast, in fast-paced, innovation-centric societies like the one we live in today, the limitations of bureaucracy are glaringly apparent.

In the modern age, nations have been forced to embrace a philosophy of continuous economic, technological, and scientific advancement in order to remain geopolitically competitive. Bureaucracy has not proved itself well-suited to this fast-changing environment, often working against progress rather than in support of it. Innovation is needed and technocracy emerges as the solution. The transition into technocracy is happening in stages, rolling out over an extended period. The pace of change is rapidly accelerating, however, and it’s clear that in the near future bureaucracy is heading for a major transformation.

One key innovation that technocracy offers over bureaucracy is to change how hierarchy is established within the organizational system. In a traditional bureaucracy, authority is typically derived from elected position, seniority, rank, and the rules governing the organization. In stable, slow-moving societies, this is fine; but in the modern age, where science, technology, and innovation are paramount, it doesn’t work, as technical expertise and scientific acumen are not prioritized in organizational decision-making. Technocracy fixes this problem by putting decision-making in the hands of those who are most intellectually capable: scientists and engineers, who work together to optimize the organization according to a metric that a central scientific think tank establishes.

Scientists and engineers within technocracy use a very different decision-making process than what you find in traditional bureaucracies, where decision-making tends to be rigid and political, with a strict emphasis on adherence to regulations, procedures, and protocols that are not always rationally defined or scientifically justifiable. In this environment, irrational biases, distorted motivations, and outside political pressures often come into play, driving decision-making toward sub-optimal outcomes. In technocracy, these shortcomings are improved by grounding decision-making in the use of the scientific method. This ensures a greater degree of rationality, since regulations, plans, and policies must now be justified on a scientific basis, with political biases and groupthink correspondingly minimized.

Capitalism’s market system has alleviated some of the inherent flaws of bureaucracy by decoupling economic decision-making from its control and granting it instead to the “invisible hand” of the market. It’s important to emphasize that “free market” capitalist economies are never truly free from governmental oversight or bureaucratic influence, however: the corporations and banks that underly capitalism are comprised of bureaucracies; markets are always regulated in some manner by the state and thus under the influence of bureaucracies; and capitalist economies are almost always tied into the national security complexes of the state, imposing them to the bureaucratic influence of the military. Thus, markets are never truly “free” - an opportunity always exists for centralized bureaucracies, whether public or private, to bias market behavior and sway it away from optimal performance.

Rather than attempt to course-correct capitalism by cleansing it of its corruption and optimizing its potential, technocracy instead proposes to replace capitalism with an entirely new approach to economics. Its advocates argued that even if you rid capitalism of the various corruptions that have plagued it, it would still be inherently flawed in its design, given its agnosticism toward the critical issue of energy optimization. Technocracy is about using science and technology to optimize energy; capitalism is about deploying money to make more money. These objectives don’t always align.

The early advocates of technocracy emerged in the milieu of the Great Depression, a time when the shortcomings of capitalism were glaringly evident. It was clear to them that capitalism’s price system was inherently flawed, leading to waste, inefficiency, and inequality. This is bad for both social cohesion and environmental sustainability: because capitalism’s pricing system does not reflect the true ecological value of resources or the energetic cost of labor, it inevitably leads to overproduction, overconsumption, and planned obsolescence, which are all disastrous for mankind’s relationship with Nature.

Unless government bureaucrats step in to regulate capitalism in an attempt to fix its inherent biases and shortcomings, the problems caused by its inefficiencies will compound. But even when they try to, do they have tools necessary to successfully evaluate the errors in the system and course-correct its behavior to fix the issues they want to address? How do they quantify environmental sustainability or social cohesion in order to regulate markets to achieve them? There is no objective standard (like with what we find with Technocracy’s energy-centered metric).

To do their job effectively, government regulators would need to develop scientific expertise and technical know-how about not only how the economy functions but also how the human system and ecosystem interact. To measure and study this, they would need a data measurement system capable of measuring both energy systems (the human system and ecosystem). And they would need a central scientific think tank to evaluate this information and form strategies and policies from it. In short, the government would have to move in the direction of technocracy to successfully control its behavior.

Thus, in order to course-correct capitalism and make-up for its inherent shortcomings, the government has to move in the direction of technocracy. At a certain point, why keep the inherently-flawed capitalist system in place at all? Why not just go “full technocracy” and move completely to an energy-based economic order? This was the question that theorists like Howard Scott and M. King Hubbard asked a century ago, and the conclusion they came up with was that technocracy is an inevitability: the natural and unavoidable progression of economic organization in the modern age.