1. The Kali Yuga: An Age of Sterility

According to the ancient wisdom teachings (also known as esoteric philosophy), Life moves through Time in a grand cyclical pattern.

At the beginning of this time cycle, Life exists in a unified, spiritual condition. This is an initial Golden Age.

As the cycle proceeds, the One Life steps itself down to become the “many lives”: meaning, it expresses itself through an infinite diversity of differentiated, individualized life forms, each evolving and growing in relation to its counterparts.

But while many appearances of individuality may come into existence, in reality the unity of life is always preserved.

Finally, at the end of the time cycle, the various differentiated life forms that have emerged and evolved through time come finally into a state of seamless mutual integration with each other, such that a unified spiritual condition is once again achieved. This marks a second Golden Age, and the conclusion of the cycle.

Note that in this pattern there are two Golden Ages, one at the beginning of the cycle, and one at its end. By contrast, only one Dark Age is experienced: this takes place at the nadir of the cycle, when the conditions of materiality, differentiation, and ignorance become most prominently expressed.

The Dark Ages is therefore the turning point in the cycle: it represents a period of time when Life’s motion into Matter reaches its peak.

From this point on, a gradual re-ascent is experienced, with things eventually ending in the re-statement of Unity.

Within the span of the total cycle, Life’s downward motion into matter and differentiation is termed “involution”. This motion culminates in the Dark Ages. By contrast, Life’s motion out of the Dark Ages and back toward spiritual reunification is termed “evolution”. It culminates in a Golden Age.

At evolution’s culmination point, when the world pattern reaches its ultimate form of expression, the time cycle is resolved and Life returns to a spiritually unified condition.

But in order to reach this final ending point, the Life moving through the cycle must first experience and push through the period or phase called the Dark Ages. This comes at the nadir point of Life’s involutionary motion into matter, where a state of “peak materiality” is reached. From this nadir point onward, evolutionary forces take over, and life begins its great ascent out Matter and back to a unified, spiritual state.

The experience of undergoing a Dark Age is therefore an inherent aspect of Time and of Life’s motion in Matter: it is a necessary “bottoming out” that must be reached before the One Life’s return journey back toward enlightenment and spiritual unity can be commenced.

In the teachings of the ancient Hindu Brahmins, the “Dark Ages” period of a great time cycle was called the Kali Yuga.

Besides the Hindus, other philosophic traditions have also emphasized this point. For example, Manly Hall writes that, “according to the teachings of Plato, the world is subject to alternating periods of fertility and sterility: fertility is to be understood as an abundance of life, so that all growth is accelerated; sterility, by contrast, infers a privation of the life principle,” with a consequent deterioration taking place throughout nature as a result.

“A period of fertility is called a golden age, and during such a time arts, philosophies, sciences, and religions flourish, and men live together in a state of concord. After a golden age, the spiritual energies decline, and the world passes into the age of silver, from there into an age of bronze, falling finally into an age of iron, which is the lowest place in the cycle of fertility.”

“In the age of iron (i.e. the Kali Yuga) the destructive tendencies gain domination and men devote their lives to the gratification of selfishness and ambition. Thus, the least degree of fertility produces the greatest degree of sterility and all noble institutions languish.”

In the grand time cycle of the world, the period of “peak materiality” was reached during the Age of Atlantis.

The fall of Atlantis was the “turning point” in the grand World Cycle. From that point on, human life was destined to begin its ascent back upward, gradually moving itself out of the material condition that it has become locked within.

The motion of human life today is part of this gradual upwelling pattern. Atlantis already took place, and today we are incrementally working to move beyond the materiality, division, isolation, and competition that characterized it.

Delving deeper, we discover that the world’s one great time cycle - its Master Cycle - embeds within itself, numerous lesser sub-cycles, with miniature golden ages and dark ages rising and falling in a complex tapestry of overlapping patterns.

Therefore, while the one, supreme Master Cycle contains one ultimate expression of a Dark Age or Kali Yuga - this taking place in the previous Atlantean age - it also contains a variety of mini Kali Yugas, which occur both before and after this singular event.

These manifest across a variety of nested time scales. Thus, there are cycles within cycles, with one great cycle containing numerous lesser cycles within itself, like parts in a whole.

The main take away is that, at any given point in its development, mankind finds itself embedded within a nested layering of Time Cycles, with one great Time Cycle containing a variety of lesser ones, each characterized by their own miniature Golden Ages and Kali Yugas.

In his teachings, Manly Hall reveals that mankind collectively entered into a miniature Kali Yuga around 3,100 BC, with this “Dark Ages” set to last for a little over 5,000 years, making its endpoint sometime around 2000 AD (now).

Doing the math, we find that the midway point of the cycle comes sometime around 600 BC, which marks the onset of a critical period of time in human history - the Axial Age - when three prominent developments in human civilization took place:

a) The birth of philosophy around the world;

b) The rise of a capitalist oligarchy in Europe; and

c) The beginning of the decline of pagan civilization, a motion that would culminate with the final destruction of the Roman Empire around 500 AD.

Here we discover that the collapse of the old Pagan order of world civilization was not accidental. Rather, it was the result of the “nadir” point being reached during this Kali Yuga sub-cycle.

This seems to be what Manly Hall is suggesting when he wrote that pagandom’s “final corruption was due to the motion of the world from a state of fertility to one of sterility. The outward indication was the increase in the political ambition of governing classes, with resultant wars and internal dissension.”

Likewise, we discover that the intense world conditions of today are also not arbitrary: they seem to be tied in with the culmination point or end phase of this 5,000+ year Kali Yuga sub-cycle.

Further elaborating on this point, Manly Hall writes that “humanity is now approaching the end of an Age of Iron (i.e. a Kali Yuga). Revulsion mechanisms are setting in; humanity is becoming weary with the sterility of its conditions. This revolt against the limitations of materialism will result in the re-establishment of the golden age, that blessed time when the gods walk with men.”

By implication, as we approach the end of the Kali Yuga, gradually we find ourselves moving out of a condition of “sterility” and back toward one of “fertility”. This motion is cosmically “supported by an increase of natural vitality,” which moves into human life, slowly but surely bringing it "toward a new birth in wisdom and truth.”

This “new birth" is man’s reward for overcoming the obstacles, challenges, and trials that it suffered through during the Kali Yuga, ones that took “the form of war, crime, and poverty, all of which must be experienced to the fullest before the mind will reject them in favor of a simpler and more mature course of action.”

By overcoming the numerous tests and trials that the Kali Yuga presents to us, mankind becomes “conditioned for wisdom.”

This points to the larger spiritual purpose of the Dark Age or Kali Yuga: man faces it not as a form of cosmic punishment, but instead as an initiatic testing grounds, where the human soul is stimulated to confront its own Shadow tendencies and materialistic attachments, work through them, and, in the end, transmute them into evolutionary growth and “soul power”.

Elaborating on this point, Manly Hall teaches that, “the forces opposing the essential progress of humanity are always embodiments of the three great enemies: ignorance, superstition, and fear. As man advances in his collective evolution, these negative obstacles supply a necessary incentive for individual improvement toward collective security.”

The Kali Yuga therefore forces us to address the existence of these “shadow complexes” within ourselves. By confronting them, we learn to overcome them, and in this way we ensure our own evolutionary growth. But, “until every possible interpretation of the qualities of the three Adversaries have been exhausted, the work toward human enlightenment must continue.”

2. The Capitalist Oligarchy Takes Hold of America

During a Kali Yuga, the spiritual principle within Life is not destroyed; rather, it becomes obscured within the “sepulcher” or “tomb” of matter.

Becoming trapped in a “sterile" material condition, Life finds itself forced to evolve upward and outward of the confines of matter, thereby liberating its energy to achieve ever higher and more refined states of spiritual expression.

As it works to liberate itself from this state of material entrapment, the energy moving through Life repeatedly encounters two adversarial forces which restrict and impede its progression: inertia and entropy.

From the standpoint of human life, these two forces of negation manifest as an innate predilection to: a) resist change (inertia) and b) engage in self-destructive, anti-social behaviors (entropy).

While these tendencies exist in all people, they sometimes become expressed in an especially strong way by certain karmically-fated individuals and groups, who embody these destructive character traits in an especially concentrated way.

As covered in our previous chapter, the Mayans gave the name “Tezcatlipoca” to persons or groups possessed by these types of negative psychological patterns.

In their myths, this embodiment of negation was personified as a destructive cult of materialistically-driven persons who, rising to power, blocked progress, dominated others, waged wars, impeded growth, extracted vitality, performed human sacrifice, and, overall, destroyed life.

In biological terms, this group of persons personifies “cancer”: it seeks its own growth at the expense of the whole, ultimately bringing about the death of the organism if not successfully confronted and overcome.

It was at the onset of the Axial Age, around 600 BC - the mid point of the Kali Yuga - that a European iteration of “Tezcatlipoca” came into existence, this taking place through the emergence a transnational caste of capitalist oligarchs.

This oligarchy came into formation by privatizing and secularizing the economic institutions of society, thereby concentrating its wealth in their own hands.

Before this period, society’s economic institutions had initially been under the control of the temple. Then, around 3000 BC (the onset of the Kali Yuga), economic governance fell into the secular control of the state. Later, around 600 BC, it fell out of state control, moving this time into the hands of private interests, who together formed an oligarchy.

We call the model of economic governance practiced by this oligarchy “capitalism”; here, the wealth of society is asymmetrically centralized into the hands of an elite syndicate of private interests, who use it to gain political and cultural control over civilization.

Rather than use their power to ensure collective prosperity and growth, the capitalist oligarchs seek to hoard those benefits solely for themselves. As a consequence of these behaviors, energy and resources are no longer flowing in an optimal way within the collective, instead concentrating in one group while being deprived in others.

This causes a corresponding state of “sterility” to take root within collective society as its various parts and appendages increasingly find themselves lacking the energy and resources required to maintain themselves as functional units.

In the end, unless society faces and overcomes the extractive, debt-ridden capitalist model that the oligarchy feeds itself off of, the collective social organism dies from starvation. In physics terms, this represents entropy winning out, deconstructing the social compound back to its base elements.

This is what happened to Rome: its oligarchs consumed all its wealth, creating a resulting fragility that barbarian invaders and internal insurrectionists exploited to bring about the fall of the empire.

After the fall of Rome, Europe transitioned into a new social order, one characterized by a partitioning and division of institutions.

Here we find religion and government becoming separated. Also, state governance and economic governance became separated, each falling under the influence of its own power elite.

Originally, in the earliest phases of civilization, these institutions were all united under the umbrella of the temple. Now, institutions are becoming separated and made partially autonomous.

After the fall of pagandom in Europe, the institution of religion came to be dominated by the Roman Catholic Church, the institutions of state by monarchs and feudal lords, and the institutions of the economy by an oligarchy of merchant bankers.

Going into a bit more detail, we find that the capitalist oligarchy that had once ruled Rome went into a period of relative dormancy after the empire’s fall, with world trade collapsing and local economic activity coming under the oversight of the Church. Meanwhile, the political structure of Europe fell into a disunited feudal pattern.

In time, this motion toward fragmentation and division would end, and things would start to become gradually interconnected once again. International trade would begin picking up; feudal states began to consolidate into monarchial kingdoms.

Alongside these developments, merchant banking oligarchies would rise once again, gradually wresting control of economic management out from the hands of the Church or monarchs.

This new economic power structure - the capitalist oligarchy - first re-emerged in the northern city-states of Italy, Venice in particular.

From there, this capitalist oligarchy would expand the reach of their economic imperium back out over the face of Europe, gaining control over and integrating back together its numerous regional economies, linking them back into world trade, and installing its favored model of financial capitalism everywhere it went.

As we explored in our previous chapter: the goal of this capitalist oligarchy was to create a global economic imperium all over the world, with them as the central ruling power lording over it as the “gods of money”.

As part of this effort, this oligarchy would eventually relocate its base of operations to England, where it would become the driving force behind the emergence of the British Empire.

But this London-based Empire was only a first step toward the ultimate goal of the oligarchy: for them, the real prize was North America. Consequently, after the American Revolution took place and the democratic republic of the United States was established, the capitalist oligarchies tried with all their might to bring their model of extractive financial capitalism here.

Eventually they succeeded, coopting America’s democratic institutions in the process and installing themselves as its ruling class.

The Esoteric Schools - the natural adversary of these oligarchs; the Quetzalcoatl to their Tezcatlipoca - had a different vision for America.

They were the ones who inspired the Founding Fathers, planned the Revolution, drafted its constitution, and sought to institutionalize the philosophical ideals of liberty, equality, fraternity, democracy, and education within the American nation.

The great challenge of the Founding Fathers, having won the Revolution and succeeded in their quest to establish a democratic nation here in America, was to now prevent the European oligarchs from moving into the country and coopting it, corrupting its democracy and installing overtop of it their capitalist model of oligarchy.

As we will see, despite a valiant struggle, this is a battle they would eventually lose: with the forming of the Federal Reserve in 1913, the capitalist oligarchs officially took possession of the country, with the plagues of Rome, Venice, and Britain now reappearing in a new Americanized form.

3. Finance Capitalism and the Rise of Privatized Central Banks

Upon its founding in 1776, the United States faced a dilemma.

It had established a democratic republic as a replacement for monarchy and it succeeded in preventing any singular religious denomination from imposing itself upon the nation, as the Catholic Church had done over the European states.

The question now facing it was: what economic model would it follow? This was a question of great debate, with two divided camps emerging, one favoring a state-lead “industrial capitalism” model and the other a oligarch-lead “finance capitalism” approach.

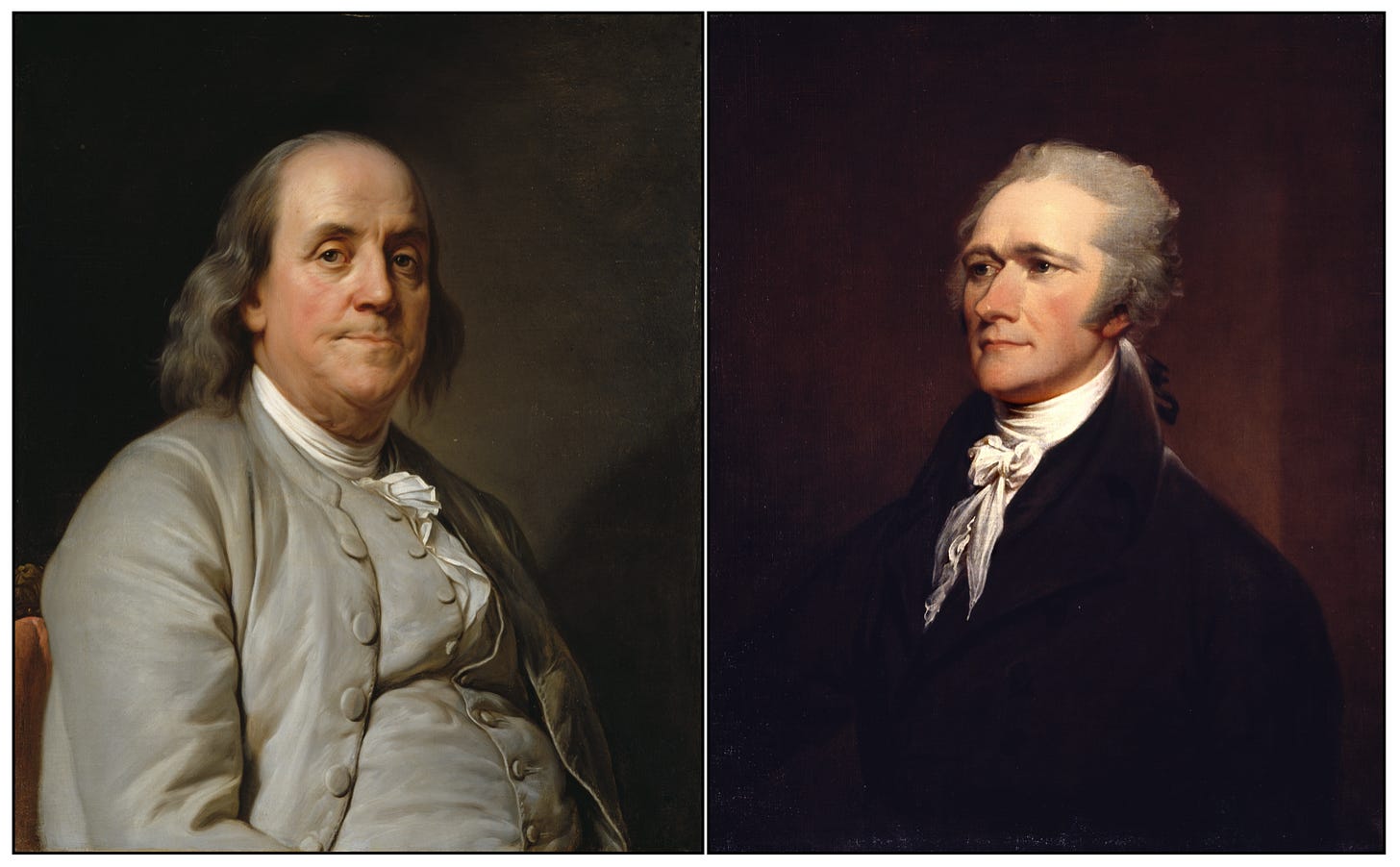

Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin were the dominant voices advocating for the former approach, while Alexander Hamilton was the lead figure pursuing the latter.

Economic historian Michael Hudson has dedicated his career to investigating the financial model of the capitalist oligarchy, a model he terms “financial capitalism”.

Financial capitalism is a model oriented around the simple idea that the only purpose of money is to make more money. It is not to fulfill collective social, economic, or cultural goals. If those happen to take place as a by-product, great. But achieving these ends are not the focal point of investment. Instead, only projects that insure the growth of monetary wealth are to be valued and supported.

Hudson contrasts this with an alternative model, “industrial capitalism” or “state capitalism”, where private enterprise exists but is regulated and guided by the state, so that the overall wealth, productivity, and quality of life of society as a whole may be increased - not just that of an elite wealth-holding class.

In industrial capitalism, money is invested in order to support the production of tangible creations, such as public infrastructure or industrial development.

Because these support the growth of overall prosperity, they will lead, over time, to the generation of enough wealth to pay back the investments put into them, with a nominal amount of interest added on top.

By contrast, finance capitalism doesn’t like to invest in long-term projects with low return yields. They’d rather pursue investments like international trade or war financing, which have shorter turnaround periods and where already-existing collateral can be easily possessed and flipped should default happen.

And the finance capitalists like big interest fees, ones that vacuum up the resources of society and concentrate it in the hands of the creditor cartels.

By contrast, there is no real desire or benefit for asymmetric wealth accumulation in industrial capitalism: it seeks instead to distribute wealth in a thoughtful manner across the various sectors of society.

In industrial capitalism, there is a natural cooperative spirit between the state, banking, and industry. But in finance capitalism, this spirit is replaced with a competitive attitude, with the bankers seeking to increase their share at the expense of both the state and industry.

Here, the elite financial capitalists come to see themselves as separate from society at large. Society is seen more or less a resource for them to mine. That’s it. So, like a parasite, they latch onto the collective, and impose their “alien” will upon it, vacuuming up its resources, energy, and wealth for themselves at the expense of the whole.

Industrial capitalism is the modern corollary to the way economic activity was organized in the beginning, with the economic management of society being coordinated with its political and cultural institutions.

The guiding idea here is that, as Hudson tells us, “the proper role of banks, insurance companies, and stock markets is to mobilize savings and credit to upgrade technology, social infrastructure, employment, and productivity.”

In this model, economic activities are brought into balance with other social, cultural, and political priorities present within society. Consequently, wealth accumulation was not incentivized because it served to imbalance and fragment the collective social unit.

This imitates man’s original social pattern, when the entire social unit was integrated together like a vast organism, with all departments of society coordinated together, each performing a vital function in relation to the total social organism.

Financial capitalism, by contrast, is motivated by very different goals. Actually, it is driven by one primarily goal in particular, to grow monetary wealth indefinitely.

As a result of the endless compounding of monetary wealth that finance capitalism seeks, a secondary consequence occurs: political power becomes concentrated in the hands of the wealth-holding class, who run and control the system together as an plutocracy.

In financial capitalism, public infrastructure and social welfare are not invested in or prioritized. This is because, in its model, money has one singular objective and one only: to grow itself indefinitely. Money is invested to make more money; that becomes its only goal. Any other motive or consideration is secondary.

There is a political consequence of this: as the private monetary wealth of the bankers and investment houses grows asymmetrically large in relation to the rest of society, their political power is correspondingly increased. For the wealth-holding class, this is a highly desired outcome.

In financial capitalism, monetary wealth is hoarded by the bankers and aristocrats, who direct it towards projects and investments that best suit their personal and private goals, not those of the collective as a whole.

The wealth of the elite capitalist class, detached from cooperative integration with the state, becomes conservative, seeking to preserve itself against any possibility of loss.

Michael Hudson explains that a short-termist mode of thinking results, which “leads them to prefer lending against collateral they can seize to pay the loan balance in case of default. The tendency thus is to look backward at what already has been produced, not forward at what may be achieved by a productive use of credit.”

This dynamic is a reflection of how financial capitalism emerged in the first place: it was born through the activities of merchant bankers, who became the first private, independent holders of financial wealth.

The focus of their investments was on providing financing to move goods that had already been produced to market, not on financing capital-intensive projects whose payoff would be long in the future. During civilization’s early eras, these types of projects were instead financed by the state.

So, rather than finance long-term investment projects with slow building payoffs, the merchant bankers instead developed an expertise putting their money to work using a safer and quicker approach: financing merchant expeditions to sell goods that the state had already financed and organized independent of their involvement.

The early merchant banking dynasties made their big breakthrough when they shifted the focus of their investments from financing trading expeditions to financing wars between competing states and monarchies.

From the perspective of the bankers, monarchs fighting wars against each other was seen as a safe form of investment, “for the simple reason that they were the ones most able to raise the funds to repay them.” This they did through the collection of taxes, which increased continuously in order to service the ever-growing interest on the government’s debt.

These war-financiers in time aligned together to form the first central banks. Thus, we find that central banks first emerged primarily under a war-making logic. Their aim was not to sponsor widespread economic prosperity, but to perpetuate to war.

This is a financial model we first saw develop in Greece and Rome during the Axial Age. Later, through the rise of the Venetian and Italian oligarchies of the Middle Ages, we find it re-emerging in the modern era.

From Italy, this central banking concept was ported over to Amsterdam, then to England, and now it has taken root in America.

In each case, as Michael Hudson writes, the only thing that the capitalist oligarchs really cared about “was the government’s power to levy taxes to raise the revenue to pay their debts.”

Then, “after the debt and tax burden had impoverished a country, they could remove their capital to other lands to repeat the process, as has happened again and again.”

In this manner, we find the first “central banks” being formed, these emerging as cartels of bankers who came together to finance and profit off the government deficits of foreign nations, created mainly due to war spending.

Moving into a territory, the banking cartel behind the central bank worked to co-opt the state, claiming for itself a private monopoly on money creation. At first, they did this by installing a gold or silver coinage system, replacing society’s older state-run credit model.

Later, they recalled the gold and silver in circulation, bringing it back into their vaults and replacing with it with a new privately issued paper bank note, which is issued by the Central Bank as a special monopolistic privilege granted by the state and legally enforced by it. Consequently, these paper notes circulate as money, replacing the gold and silver coinage that preceded them.

Based on this “fiat banking” model, modern central banks have risen to control the domestic economies of nations around the world.

The first example of a modern central bank was the Bank of England, formed in 1694 after it was sold by the crown a monopoly on issuing bank notes, whose value the government underwrote by accepting them in payment of taxes.

A similar situation took place in America with the founding of the Federal Reserve in 1913. Here, a private cartel of banks gained monopolistic control over the country’s currency issuance. Ever since, the United States has not been a fully sovereign, democratic entity, with its economic policies dominated by the private interests of the banking cartel running its central banking system.

4. Unproductive Debt and the Bubble Economy

In Michael Hudson’s view, the type of lending preferred by financial capitalism is one based around the use of what he calls “unproductive debt”.

Because this form of investment does not result in an increase to the overall productivity, growth, or prosperity of society as a whole, it is termed “unproductive”.

Instead of being used to support widespread economic growth, prosperity, and the rise in standards of living for the population as a whole, debt is used to finance war, asset price inflation, and other forms of wealth-extracting and prosperity-reducing activities.

Contrasting this is “productive debt”, where financial investments are made with the explicit goal of generating resources and assets that borrowers can employ in order to earn enough profit to repay the debt with its stipulated interest.

In finance capitalism, these aims are not prioritized; instead, investments are made in areas where assets have already been produced and can be pledged as collateral should the investment opportunity fail.

Productive debt is the basis of developing and growing industry, while unproductive debt is detached from industrial investment, seeking instead to lend against pre-existing assets that can be collateralized and subsequently seized and sold off in case of default.

When a financial system favors the use of unproductive debt, a situation results where the interest payments on these loans has to be paid out of a fixed or shrinking economic pie.

Since the money wasn’t invested with the aim of growing the overall economy, the principal and interest on the loan must therefore be extracted out of a non-growing or even shrinking economic system.

The amount of extraction taking place increases exponentially over time, as the interest compounds. This kind of debt therefore tends to hang over society as an ever increasing weight or burden - a rising tide of pressure that threatens to drown everyone in the debtor class.

As Karl Marx once described it, financial capitalism’s preferential use of unproductive debt does little for industry, but does a marvelous job at centralizing money wealth: “It does not alter the mode of production, but attaches itself as a parasite and makes it miserable. It sucks its blood, kills its nerve, and compels reproduction to proceed under ever more disheartening conditions.”

Explaining Marx’s simple financial model for comparing industrial verse financial modes of capitalism, Michael Hudson writes that “industrial capital makes profits by spending money to employ labor to produce commodities to sell at a markup, a process he summarized by the formula M-C-M’, where money (M) is invested to produce commodities (C) that sell for yet more money (M’).”

However, in financial capitalism, “usury capital seeks to make money in ‘sterile’ ways, characterized by the disembodied (M-M’).” Here, the aim of capital is “not to increase commodity output or cut the costs of production, but to make money from money itself (M-M’) in a sterile ‘zero-sum’ transfer payment.”

In this model, based upon the use of “unproductive debt”, money seeks to grow independently from involvement in tangible production. And as a consequence, "financial claims become a financial overhead that eats into industrial profit and cash flow.”

In his writings, Michael Hudson highlights the fact that, like Marx, Adam Smith, the famous 18th century British economist, was also a critic of finance capitalism’s use of unproductive debt.

He writes that “Smith criticized the royalist governments of his day for indulging in vainglorious territorial wars that burdened the economy with (unproductive) debt.”

In Smith’s view, “these wars were seen to be economically corrosive, not only as a result of their direct costs in terms of manpower and material, but also the post-war legacy of public debts that loaded down the economy with taxes to carry their interest charges.”

Hudson also notes that Adam Smith “just as harshly criticized government for financing these debts by creating and selling off monopoly privileges” to private capitalist interests, something that has now become common practice.

For example, “in England, the East India Company and the Crown corporations burdened consumers by charging extortionate prices. Seeking profits in this way weighed down the nation’s cost structure.”

Hudson comments that “the sanctioning of such public monopolies was hardly an example of industrial planning.” In fact, it was more like the opposite, since “privatizing the revenue generated by public enterprises or natural resources in the public domain involves both a fiscal and a financial sacrifice,” for the reason that “relinquishing these revenues obliges governments to make up the difference by taxing labor and tangible non-financial capital.”

As a consequence of financial capitalism’s use of unproductive debt, we find the macroeconomy as a whole assuming the responsibility for servicing an ever-increasing debt load.

And yet, the debt load the economy is tasked with paying back wasn’t originally invested to grow or expand it; rather it was used for unproductive purposes like war.

Consequently, the debt payments it must now service must be paid out of the macroeconomy’s fixed or shrinking productive output, leaving less and less available for everyone else.

What results is a classic “Kali Yuga”-style sterilization of society, where the population as a whole finds itself increasingly starved of the energy and resources it needs to reproduce itself, these having instead been vacuumed up by plutocrats and oligarchs whose thirst for wealth can never be satisfied.

Meanwhile, the debt load over society keeps compounding, making the process exponentially worse over time.

The consequence of this is what is called “debt deflation”: as the unproductive debt load increases, a corresponding deflation in the wealth, health, and cohesiveness of society at large sets in.

Here, the rising debt load has the effect of reducing demand for commodities and services, since the money that would be used to pay for them is instead being paid to service the debt. With decreasing consumer demand comes the contraction of industry and an increase in unemployment, which together serve to further impoverish society, making the burden of servicing the mounting debt load ever worse.

Overall, we find that the objective of finance capitalism is “not to fund industry, but to load it down with debt; not to finance public investment, but to dismantle and privatize it.”

Hudson emphasizes that, “under such conditions fortunes are made most readily not by industrial capital formation but by indebting industry, real estate, labor and governments, siphoning off the economic surplus in interest, other financial fees, bonuses, and ‘capital gains’.

We therefore find that the oligarchs behind finance capitalism together form a cartel of vested interests whose activities are fundamentally “at odds with the rest of the economy and its industrial competitiveness.”

In this manner, the oligarchs behind the implementation of financial capitalism come to embody the archetypal qualities of “Tezcatlipoca”: the Adversary of human progress who personifies the forces of entropy and negation.

In classic Tezcatlipoca fashion, the banking oligarchs maintain their own wealth addiction by drawing out and preying upon this same tendency within the psyche of the populace.

The oligarchs’ monopoly on money creation, combined with their usurious lending policies, ensures that society at large will become both physically and psychologically dependent on finding and obtaining money - a resource they make deliberately scarce.

This drought situation then creates a mad scramble within all tiers of society, as everyone attempts to capture and hold onto this scare resource for themselves. This brings out a competitive, self-interested mode of psychology and results in a moral and ethical “race to the bottom”, as people resort to increasingly desperate and unethical measures to obtain money to stay one step ahead of the ever-compounding pressure of interest.

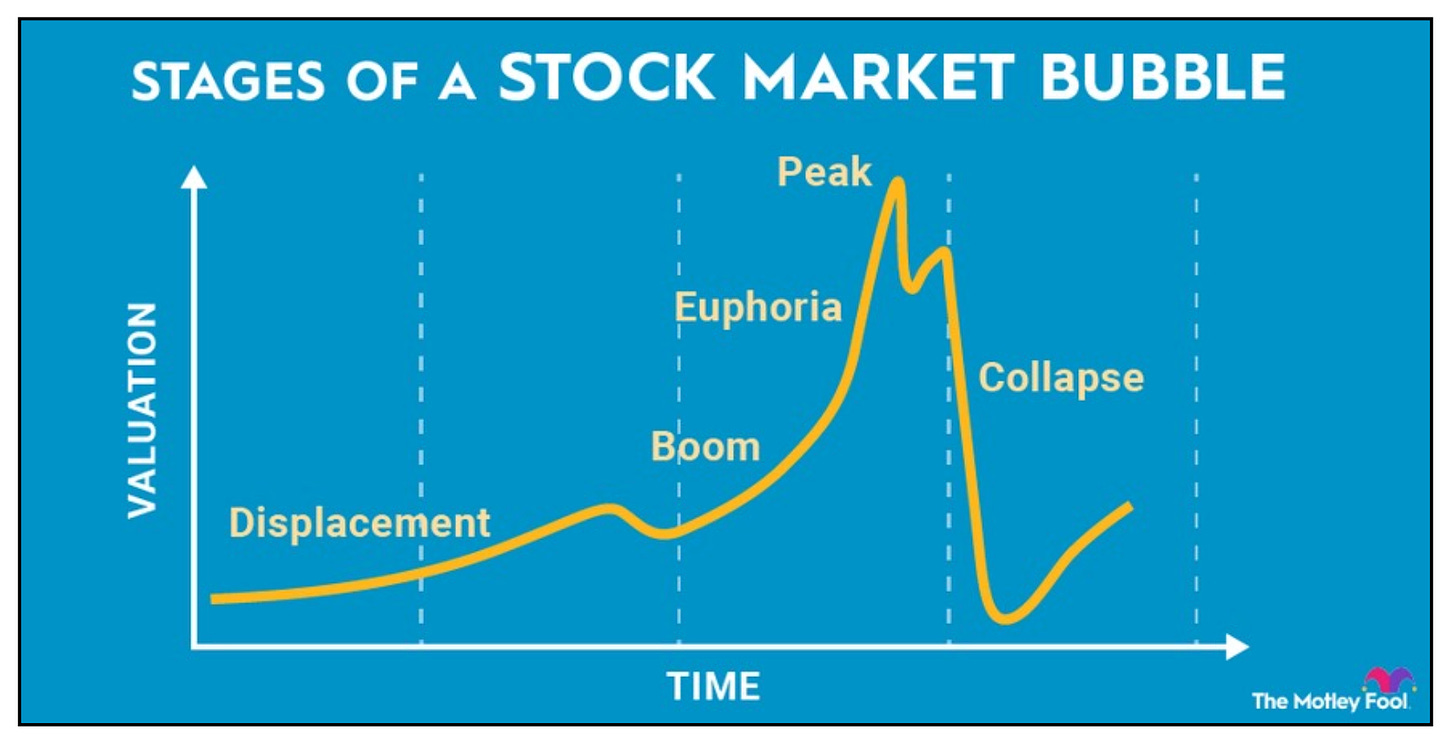

Like a malignant tumor, the oligarchs behind financial capitalism replace real, tangible economic growth with a financialized “bubble economy”.

As Michael Hudson further explains, “instead of funding new means of production whose future revenues will be able to repay their loans with interest, ‘bubble’ credit is extended to borrowers to bid up the price of corporate stock, real estate, and other assets already in place.”

“The ‘bubble’ or Ponzi phase of the financial cycle aims to create the financial equivalent of a perpetual motion machine, sustaining an exponential debt growth by creating enough new credit to continuously inflate real estate, stock and bond prices at a rate that (at least for a while) enables debtors to cover the interest falling due.”

“The underlying dynamic is fictitious, because it cannot remain viable for long. It sustains interest payments by stripping assets, leaving the economy with less ability to produce a surplus out of which to pay creditors.”

In true Tezcatlipoca fashion, by means of this evil and extractive system “the financial sector destroyed life on a scale similar to military conquest. Birth rates fall, life spans shorten, emigration soars, and economies polarize.”

The financial policies that underly this system are clearly entropic in nature: by saddling society with an ever-increasing, nonproductive debt overhead, they gradually starve the social organism, killing it and dissolving the compound.

In sum, the economic policies of the West have fallen into the hands of a financial oligarchy who “knows nothing about production and has nothing to do with it.”

Instead, the western oligarchy’s model of “finance capitalism has become a network of exponentially growing interest-bearing claims wrapped around the production economy. The internal contradiction is that this dynamic leads to debt deflation and asset stripping. The economy is turned into a Ponzi scheme by recycling debt service to make new loans to inflate property prices by just enough to justify new lending.”

In its final stages, “the ‘real economy is unable to grow at a rate required to support the growth in debt service. … Financial claims rise exponentially, beyond the economy’s ability to pay.”

Bubble economies are inflated “to try to postpone the inevitable crash by inflating prices for real estate, stocks, and bonds by enough to enable debtors to take out higher loans against the property they pledge as collateral.”

As another tactic to cope with the rising debt overhead, “governments balance their budgets by privatizing public enterprises, selling tollbooth privileges on credit to buyers who bid up their prices by debt leveraging.”

“What is irrational in all these policies is the view that it is anything other than impossible for the real, productive economy to ever support the exponential growth of compound interest, especially in a situation where economic productivity is being systematically eroded by the expanding financial overhead.” (Hudson)

This is the underlying reality of finance capitalism: it must always destroy society and therefor itself.

There is no future in it, but it serves a purpose. Like Tezcatlipoca, it latches onto society as a self-destructive force, deconstructing the compound so that its elements can be recycled into the production of a new form.

When this entropic force took down pagandom, the modern age was born in its place. We are now at the cusp of another deconstruction - the “Great Reset”. The question now is: after this deconstruction occurs, what will rise this time to take its place?

5. America’s Early Battles with the Capitalist Oligarchy

With this examination of the difference between industrial vs. financial capitalism and productive vs. unproductive debt now under our belts, we can better appreciate the dilemma facing the young American nation at the point of its founding.

The constant attacks on America during its early decades by the British and French crowns kept the young country in a state of near-constant war. It therefore found itself in the position of needing a national banking system to help finance and coordinate America’s war-making capacity.

But how do you prevent this central bank from bogging society down with unproductive debt, a situation that would promise to sink the country into the same situation of debt entrapment that the European states had already become enmeshed within for centuries?

In his research, Michael Hudson reveals that these questions and concerns were at the forefront of American economic thought during the early decades of its formation.

To give an example, he cites one early American critic of financial capitalism, Daniel Raymond, who wrote that “every money corporation is prima facie injurious to national wealth. … They are and ought to be considered as artificial engines of power, contrived by the rich for the purpose of increasing their already too great ascendancy and calculated to destroy that natural equity among men which God has ordained and which government has no right to lend its power in destroying. The tendency of such institutions is to cause a more unequal division of property and a greater inequality among men than would otherwise take place.”

But other American commentators were more sympathetic to the need to form some type of central banking entity, for the reason that this would help facilitate America’s war-making capacity.

For example, Hudson cites another 19th century economist as writing that “the military power of a nation is measured by the amount of industry which it can divert into the channels of war”, that is “by the size of its economic surplus in the form of military hardware and support of soldiers.” Consequently, “the issue of fiat money (from a central bank) could enable governments to pay for military service and technology, diverting output (and the labor to produce it) to government use by displacing civilian spending on food, clothing, and other necessities”.

Influenced by the latter form form of thinking, Alexander Hamilton, one of America’s founding fathers and its first Treasury Secretary, worked to establish the nation’s first national bank, the Bank of the United States, based around the private ownership model of the Bank of England.

He was opposed by Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and others, who worked to block the chartering of any such privately-owned national bank in America.

American historian Helen Hodson Brown provides the background details to this story. She writes that “prior to the American Revolution, most of the colonies printed their own paper money — debt-free — and actually made loans to farmers and businessmen. The result was a booming economy and almost full employment.”

When Benjamin Franklin went to England prior to the revolution, he was asked about the source of the colonies’ prosperity “by the directors of the Bank of England,” and Franklin responded that, unlike with the financial capitalism model that had taken root in England through this bank, the governments of the colonies directly issued their own paper money “in proper proportion to the demands of trade and industry.”

She cites Franklin as having further stated that: “In the colonies we issue our own money. It is called Colonial Scrip. We issue it to pay the government’s approved expenses and charities. We make sure it is issued in proper proportions to make the goods pass easily from the producers to the consumers. … In this manner, creating for ourselves our own paper money, we control its purchasing power, and we have no interest to pay to anyone.”

Franklin then continued: “You see, a legitimate government can both spend and lend money into circulation, while banks can only lend significant amounts of their promissory bank notes, for they can neither give away nor spend but a tiny fraction of the money people need. Thus, when your banks here in England place money in circulation, there is always a debt principal to be returned and usury to be paid. The result is that you have always too little credit in circulation to give the workers full employment. You do not have too many workers, you have too little money in circulation, and that which circulates, all bears the endless burden of unpayable debt and usury.”

Apparently, Benjamin’s Franklin’s words became a major source of anxiety for England’s central bankers.

In his book “Babylon’s Banksters”, Joseph P. Farrell writes that “England’s banksters were not about to allow this situation to continue, allowing the colonists to gain prosperity without enriching their own parasitic coffers. Thus, the Bank of England parlayed its influence in Parliament to get the 1764 Currency Act passed, which made it illegal for the colonies to issue their own money.”

Predictably, as a consequence of installing their extractive capitalist model upon the colonists, “a year later the streets of the colonies were filled with the unemployed and beggars. And it was this substitution of debt as money, the replacement of real money by the facsimile of money, that, according to Franklin, was the real cause of the Revolution.”

Due to Franklin’s opposition to the project, Hamilton had to wait until after his death in 1791 to found his national bank project, doing so “despite the fact that the US Constitution clearly placed control of the nation’s currency in the hands of Congress, and made no provisions for Congress to delegate that authority.”

Historian F. William Engdahl points out that the “Constitution had been designed specifically to keep the American money supply out of the hands of the private banking industry, and keep it directly in the hands of what Jefferson, the drafter of the Declaration of Independence, called the most republican of the three branches of government, that of the elected Congress.”

Engdahl further emphasizes that “Hamilton’s national bank was no United States Federal Government bank. By its charter, it was 80% owned by private investors, including — remarkably enough for a young nation not yet healed from the wounds of an independence war — investors from the largest British banks.”

“The Bank was administered by a President and a twenty-five person Board of Directors. Twenty of the twenty-five directors were elected by the stockholders, 80% of whom were private groups. Only five were appointed by the Government. The US Government in effect handed over to private bankers control over its money and agreed to pay those bankers interest to boot on money it borrowed”

Notably, “Nathan Rothschild, at the time London’s and the world’s most powerful banker, invested heavily in the first Bank of the United States, becoming by some accounts its largest shareholder. By guiding the activities of the Bank of the United States from behind the scenes, the London bankers set about to control financial activity and credit in America, something many Americans viewed as tantamount to their recolonization by Britain through financial and economic means.”

The first national bank established by Hamilton would eventually be demolished and its charter not renewed, this victory being won by a well-organized political opposition in Washington. But it would not disappear for long, with two other iterations following it over the course of the 19th century.

Political opposition against allowing a private banking cartel to take control over the domestic economy of the young American nation was lead by Andrew Jackson, who mobilized his constituency in order to eliminate the national bank effort of the oligarchs.

This campaign succeeded, at least for a while. But a coordinated campaign by US and European capitalists (with the Rothschild dynasty at the forefront) aimed to counter this situation by engineering a series of financial panics, recessions, and depressions in the country, these generated with the intention of undermining the American economy so as to coerce the government to re-establish the charter of its privatized central bank.

During the 19th century, the bankers were never able to gain the total victory they sought. As Engdahl informs us, “repeated attempts by the money interests to re-establish control over the nation’s money through a central bank under their private control continued without success right up to 1913,” when the capitalist oligarchs finally achieved their great victory and established the Federal Reserve central banking system.

The ultimate consequence to the country of establishing this privatized central banking system - the Federal Reserve - was that it lost its sovereignty. The nation was now in a position of dependency upon the economic and political decisions of a private, self-interested banking oligarchy - a situation that is inherently antagonistic to the preservation of its democratic institutions.

Today, we see the consequences of this turn of events all around us.

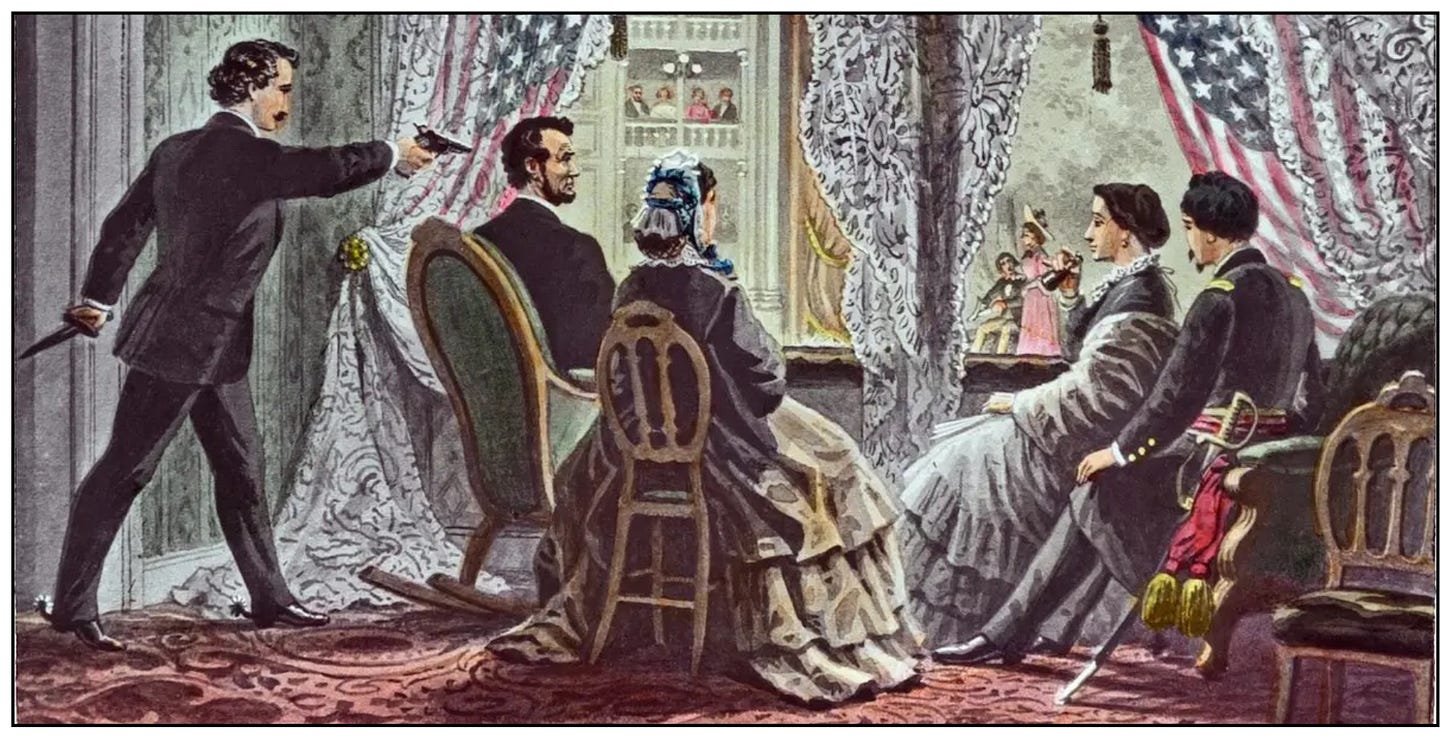

6. Lincoln, the Civil War, and the Greenback

Over a half century after Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson fought Hamilton to keep America free from the infestations of financial capitalism and oligarchy upon its shores, Abraham Lincoln resurrected the cause.

Engdahl cites Lincoln as having stated, during the Civil War of the 1860s, that “money is the creature of law and the creation of the original issue of money should be maintained as an exclusive monopoly of National Government.”

Here we find Lincoln endorsing the state-centered model of industrial capitalism. He stated that “government, possessing the power to create and issue currency and credit as money and enjoying the right to withdraw both currency and credit from circulation by taxation and otherwise, need not and should not borrow capital at interest as the means of financing governmental work and public enterprise.”

Instead of borrowing the money it needs to finance itself from private banking syndicates, “the Government should create, issue, and circulate all the currency and credit needed to satisfy the spending power of the Government and the buying power of consumers. The privilege of creating and issuing money is (therefor) not only the supreme prerogative of Government, but it is the Government’s greatest creative opportunity.”

Ultimately, Lincoln envisioned a state capitalism model as being the best fit for America, one patterned after the original pre-plutocratic economic systems of the early Mesopotamian states. Here, “the financing of all public enterprise, the maintenance of stable government and ordered process, and the conduct of the Treasury will become matters of practical administration. The people can and will be furnished with a currency as safe as their own Government. Money will (then) cease to be master and (instead) become the servant of humanity. Democracy will rise superior to the money power.”

Based on this approach, during the Civil War Lincoln financed the North’s war efforts with “Greenbacks”, which were state issued and consequently “avoided entangling the Union in large war debts to the private bankers”.

Going deeper into the dynamics of Lincoln's Greenback currency system, Engdahl writes that “rather than establish a new Third Bank of the United States — again to be controlled by private bankers, as leading London and allied New York bankers wished — Lincoln used the powers of the Constitution to convince Congress to authorize the issue of interest-free Legal Tender Notes in the amount of $150 million (an enormous sum at that time), backed by the Full Faith and Credit of the United States Government.”

“During the course of the Civil War, the volume of these government-authorized Greenbacks in circulation was increased to $450 million. The Greenbacks could not at the time of issue be redeemed in gold. They were US Government fiat paper notes—i.e., promises to pay the bearer in gold or silver at some unspecified date in the future. The holder of the note was, in effect, betting on the future existence and prosperity of the United States.”

As one might expect, “Lincoln’s policies were not at all well received in the City of London, where the powerful House of Rothschild and other City banks planned to entice a desperate Lincoln Government to accept war loans at usurious interest rates.”

Engdahl points out that, at the time, “the London banks, led by the House of Rothschild, were the major creditors to the Southern cotton trade, the vital source of raw cotton for the Manchester, England textile mills.”

Consequently, “Lincoln, who had won the Presidency on his strong support for industrial protectionism, was faced with the secession of Virginia and six other Southern cotton-growing slave states immediately after his election. … The Southern secession had been discreetly encouraged by August Belmont, serving as Rothschild’s personal agent in the United States, and now a major figure in American politics. Belmont regarded Lincoln’s protectionist policies as anathema. US protectionism and high tariffs would have destroyed England’s lucrative cotton business with the slave states.”

We thus discover that the larger battle for control of America’s monetary system between the oligarchs and the democrats was the major driving force behind the Civil War.

Lincoln is a great American hero not only because of his work in eliminating the evil institution of slavery but also because he succeeded in forestalling the capitalist oligarchs’ takeover of the country.

But Lincoln paid a heavy price for his bravery: he was assassinated as result of his wartime monetary policies.

Investigating further the underlying dynamics and conspiracies that set the Civil War into motion, Joseph Farrell cites the commentary of the famous German Chancellor, Otto Von Bismarck, who watched the whole episode play out from his vantage point in Germany.

In 1876, shortly after the end of the Civil War in America, Bismarck wrote: “‘I know with absolute certainty, that the division of the United States into federations of equal force was decided long before the Civil War by the high financial powers of Europe.”

“These bankers were afraid that the United States, if they remained in one block and as one nation, would attain economic and financial independence, which would upset their financial domination over Europe and the world. Of course, in the ‘inner circle’ of Finance, the voice of the Rothschilds prevailed. They saw an opportunity for prodigious booty if they could substitute two feeble democracies burdened with debt to the financiers … in place of a vigorous Republic sufficient unto herself. Therefore, they sent their emissaries into the field to exploit the question of slavery and to drive a wedge between the two parts of the Union.”

As a consequence of this conspiracy, “the rupture between the North and the South became inevitable; the masters of European finance employed all their forces to bring it about and to turn it to their advantage.”

Due to the actions of Lincoln, who refused to go into debt to the bankers to finance the war, “the Government and the nation escaped the plots of the foreign financiers.” But the bankers, who “understood at once, that the United States would escape their grip”, sought their vengeance. Consequently, “the death of Lincoln was resolved upon.’”

7. The East Coast Establishment and the Gold Standard

Undeterred by Lincoln’s victory in the Civil War, the oligarchs continued their financial assault against the American nation.

In the decades leading up to the onset of the 20th century, this oligarchical class, comprised during this period of an alliance of New York and European banking interests, sought to strategically undermine the domestic US economy, bringing it into repeated recessions and depressions in order that they might sweep in with their pre-planned prescription for the fix: privatized central banking.

Their plan revolved around undermining the US government’s wartime Greenback currency, replacing it instead with a gold specie-backed currency, which they held near monopolistic control over.

As F. William Engdahl further explains, “the goal was to allow those holding monetary gold — namely, London and an elite circle of allied New York international bankers — to control the US currency by locking US currency issuance to gold.”

“At that time, most of the world’s central bank gold was in the hands of the Bank of England and the London banks.” Therefore, the switch from US bank notes to gold would be a strategic victory in the European banking oligarchy’s long-held plan to take control of America’s domestic economy and political system.

The US-based political lobbyists behind the bankers’ campaign to substitute gold specie for US bank notes were representatives of New York, Boston and Philadelphia banks who specialized in financing international trade and therefore held large stores of gold. This constituency also featured international shipping and trade corporations, who used gold specie in their international transactions with British and European suppliers.

In time, this American pro-gold constituency would come to be known as the “East Coast Establishment”. Engdahl explains that it “had its origins in this internationalist banking-centered group of powerful New York and East Coast families. They organized pressure on Congress through their lobby organizations.”

These East Coast capitalist oligarchs were bitterly opposed by a mixed alliance of Western and Southern agriculture interests, a major share of the nation’s iron industry, and associations of small businessmen, all of whom would be threatened and weakened by the conversion of America from an “industrial capitalism” to “financial capitalism” model.

Engdahl elaborates: “The Specie Resumption Act was highly controversial and bitterly opposed by farmers and small manufacturers who feared a major deflation of the economy and contraction of the money supply.”

"They rightly complained that as the New York and New England bankers held the bulk of the nation’s monetary gold, then therefore the distribution of the nation’s currency would be skewed towards those same East Coast banking powers.” Therefore, the Specie Resumption Act “would most benefit those banks at the expense of the rest.”

Despite this organized opposition, “a syndicate of New York and London international banks finally pushed through the Act in 1875.”

The dominant players in the banking syndicate that mobilized this effort included, on the European side, August Belmont & Co., representing London bankers N.M. Rothschild & Sons, and, on the American side, Drexel, Morgan & Co., whose partner was J.P. Morgan and who represented Junius S. Morgan & Co. of London, the bank of J.P. Morgan’s father.

The passing of this act was perhaps the biggest strategic victory the capitalist oligarchs had won up to that point. As Engdahl points out, its passage “was a major step towards bringing the US economy under the control of London and New York international bankers because they controlled the lions’ share of the world’s monetary gold.”

Unsurprisingly, there were dire consequences for the American republic as a result of this Act. Farrell notes that, “predictably, the Act led to a vastly shrunken money supply, unemployment, and the Depression of the 1870s.”

The gold conspiracy of the bankers lead directly not only to the Depression of 1873, but also to a second depression that took place two decades later, in 1893.

To the bankers, the contraction of America’s economy was seen as desirable: it gave them further leverage over the state to enforce even more drastic changes to the US economic system, ones which would serve to further benefit the capitalist elite at the expense of everyone else.

All the banking cartel really cared about was implementing their gold standard; the suffering, hardship, and death this caused were seen as necessary evils to support the cause. Their gold-backed system allowed them to drastically increase their already considerable power and wealth at the expense of everyone else - that’s all that mattered. Classic parasitic behavior.

While numerous constituencies within the East Coast Establishment stood to benefit from the implementation of the gold standard, two financial powerhouses were particularly enriched: the Rothschild banking dynasty from Europe (working through their point man, August Belmont), and the House of Morgan in America, lead by JP Morgan in New York and his father, then stationed in London.

The Morgan and Rothschild dynasties formed a close partnership in the latter decades of the 19th century, as both had much to gain from the capitalist oligarchy’s takeover of the US economy.

Farrell writes that, in the 1890s, the House of Rothschild and the House of Morgan together conspired to put their appointed political representative, President Cleveland, into office. It was through him that they brought the dollar fully onto the gold standard, making them, as the world’s two largest gold holders, the new controllers over America’s money supply.

The Panic of 1893 that resulted from this campaign lasted four years, becoming an 1890s version of the Great Depression. It was caused, like its later 1930s counterpart, by a contraction of bank credit across America. As a consequence of this, “spending for capital goods collapsed, profits plunged, and depression hit the cities en masse. Over the course of this depression 15,000 businesses, 600 banks, and 74 railroads failed. There was severe unemployment and wide-scale protesting, which in some cases turned violent.”

For the banking oligarchs, notably Morgan and Rothschild, this Depression provided a wonderful opportunity for them to not only consolidate their control over America’s money supply, but also its railroad industry - the heart of its economy.

Farrell explains that the chain of major railroad bankruptcies that resulted from the banking panic engineered by these bankers provided “a 'golden opportunity’ for the highly solvent banks of the Morgan-Belmont syndicate to consolidate their iron grip over the expanding US railway network, at that time the heart of American economic expansion.”

JP Morgan in particular won big with this consolidation move: he “used the crisis to gain control of the most strategic steel and railroad industries of the United States. In 1901 he gained control of US Steel, which he created out of mergers of Carnegie Steel and others to form the world’s largest steelmaker.” In addition, during this consolidation frenzy, “Morgan created the vast General Electric Company, International Harvester, and countless other major industrial groups.”

As the 19th century came to a close, JP Morgan emerged as the dominant hierarch of the oligarchy that had taken hold of America. As we will see in subsequent chapters, this pivotal figure would come to play a fateful role in steering the course of world history - in some ways obvious, in other ways less well known.

Overall, the late 19th century was the period when oligarchy began to take over American democracy - with this motion of events culminating in the founding of the Federal Reserve, America’s privately operated centrally banking system.

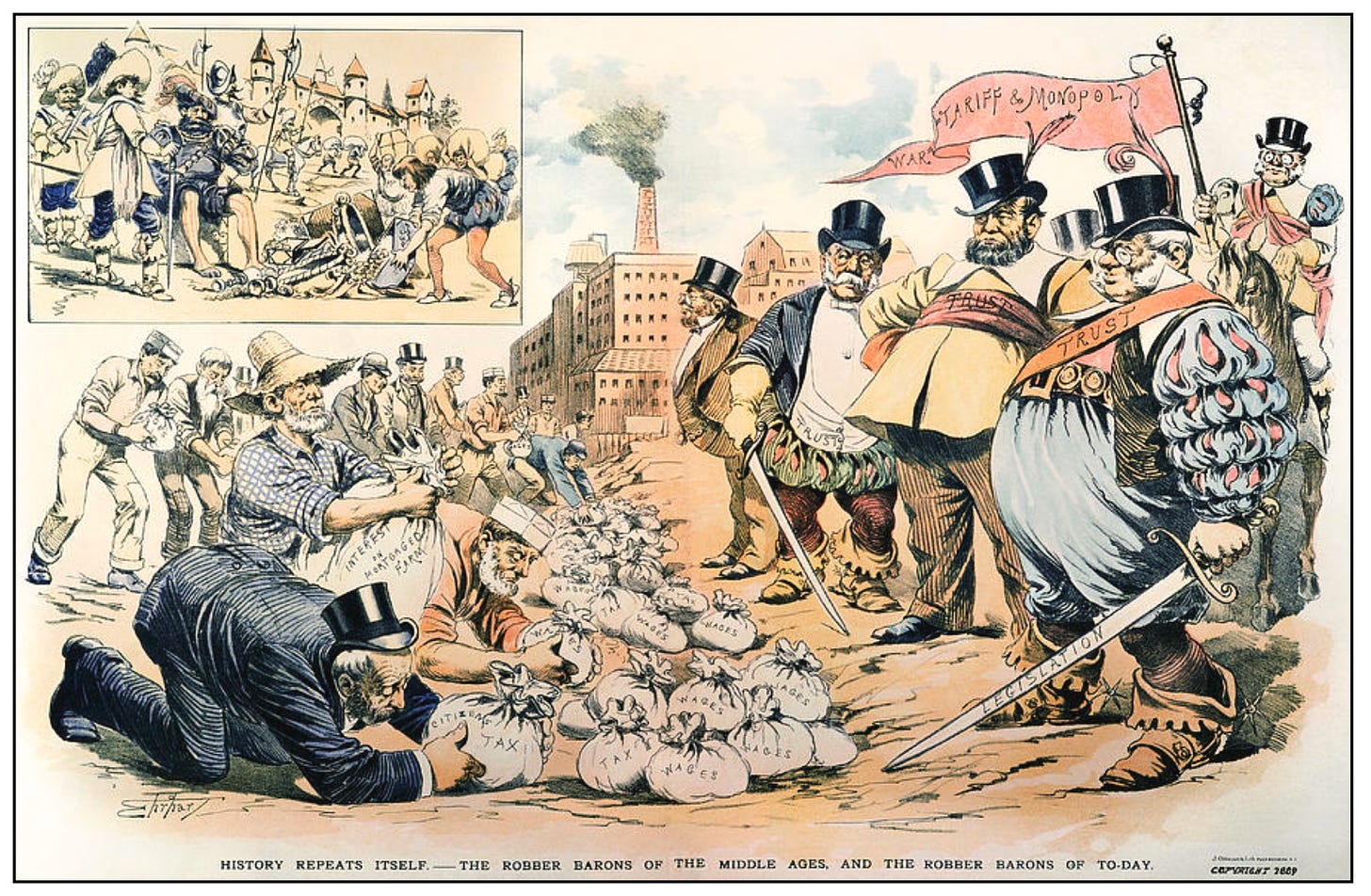

William Engdahl writes that, by the end of the 1890’s, JP Morgan, alongside other “Robber Barons” such as Lord Rothschild and John Rockefeller, “had become the giants of an increasingly powerful Money Trust controlling American industry and government policy. There was little room for the actual practice of democracy in their world. Power was the commodity of their trade.”

Here we find “the creation of an American aristocracy of blood and money, every bit as elite and exclusive as the titled nobility of Britain, Germany or France – despite the Constitutional ban on titled nobility in America. It was an oligarchy, a plutocracy in every sense of the word— rule by the wealthiest in their self-interest.”

In symbolic terms, the Adversary had taken control; Tezcatlipoca had driven out Quetzalcoatl, and was ruling over the land as a tyrant. This course of events set the stage for everything that would follow in the 20th century, as America’s “fight with the Shadow” moved into a new and critical phase.

8. America’s Fight with the Shadow Continues

Calling back to our earlier discussion of Mayan mythology from the previous chapter, remember that Tezcatlipoca was associated with rise of an evil cult of black magicians, who fetishized power, were addicted to war, and practiced human sacrifice.

Are today’s capitalist oligarchs, with their unquenchable thirst for power and wealth, their war-profiteering, and all the economic hardship they cause, not guilty of the same crimes? Do they not embody, in the modern age, the same “Shadow” archetype as Tezcatlipoca?

Like Tezcatlipoca, the capitalist oligarchs follow no moral imperative or sense of higher purpose in their actions. Their motivations are entirely self-seeking - to expand and consolidate their own wealth and power, and any cost in terms of human sacrifice is worth it - a “necessary evil”.

This modern iteration of Tezcatlipoca was not a natural creation of the Americas. Rather, it was ported over from Europe, not willingly or voluntarily, but through decades of careful plotting and strategizing by European banking dynasties, who had already taken control of their home continent and were now looking to expand their base of operations into the Americas.

The American Constitution was designed to try to prevent this powerful syndicate from taking political and economic control of the American nation, but, after decades of waging covert financial warfare against this country, the banking oligarchs finally won out.

In this manner, the whole economic tradition of Europe, with its debt-based economics, was translated here, this process beginning almost immediately after the founding of this country. As Manly Hall points out, “that mistake set us back two hundred years.”

Hall explains that “our entire economic system is merely the transplanted European theory of coinage. We just moved it here. And that was a very serious error, for we created a conflict: between traditions of the past and innovation.”

Instead of building a new civilization from scratch, one guided by the high philosophical ideals of Francis Bacon and inspired by the peaceful Mayan and Incan empires of the past, Americans instead “fell back upon European tradition for everything. … What we call American civilization is therefore merely European culture transplanted to a new environment.”

Hall wryly observes that “we fought the Revolutionary War to free ourselves of European interference, and then promptly accepted an economic system that was the supreme interference.”

In particular, “the economics we use belonged to medieval Europe,” and before that to fallen Greece and Rome. It didn’t work for them, and it won’t work today. Again and again, financial capitalism and oligarchy have proven themselves unsound, inadequate, and immature. And yet here we are, embracing them once again as the foundation of our modern way of life.

The monstrous economic system that has been built up in this country over the past 150 years, since the onset of the Guilded Age, has taken hold of America - and through America, the world - as a great parasite: an unnatural, vampire-like Shadow monster that sucks the life out of society in order to feed and grow itself.

In other words, it is Tezcatlipoca, the “Adversary”, reborn in a modern context, reappearing individually through the persons of greedy oligarchs and collectively through the structure of an unsound and unsustainable economic system.

Both work together to impede and block progress, creating a barrier between us and the destiny that we are meant to fulfill.

Of course, this is the classic role that the “Shadow” always plays in human life: it rises as an Adversary to impede and block the realization of a greater state of evolutionary advancement.

Consequently, to attain the growth we are seeking, and to move beyond our current state to a higher form of collective existence, we must first confront and address the Shadow.

Here, we discover that the Shadow is not an “alien” entity; actually, it is the karmic manifestation of the weaknesses and negative forces we maintain within ourselves. It rises as a projection of the Shadow traits we keep within ourselves, and we cannot face and defeat it until we are ready to address and overcome the forces of negation we continue to maintain internally within ourselves.

In the case of this modern Shadow manifestation, it feeds off the greed, egotism, competitive instincts, and superstitious idolatry of wealth that most of us maintain within ourselves in some capacity. Without these character traits being widespread, the plagues of financial capitalism could not take root.

Therefore, to overcome this Adversary and break through to a higher state of self-realization, we must turn and face these forces within ourselves. If we can overcome their lure within our personal psychologies, then we can come together to fight and win our battle with the oligarchical Shadow entity that has risen to personify these negative tendencies on a collective scale.

Manly Hall emphasizes that “We have to break up the old patterns. It is the only way we can free ourselves to build new patterns.” This requires “a complete breaking up of most of the intolerances we cherish,” including: racial superiority; flawed scientific notions; the theory of competitive politics; the interest system in economics; and world exploitation.

While the heritage of the oligarchical Adversary we face today began back in Europe, it is now America that is its global home base. Consequently, it is here in America that the great battle against the Shadow must be fought and won.

Manly Hall writes that “the natural temperament of our people is to be the greatest inventive and constructive genius of any people on Earth.” This genius “comes from the very earth beneath us here in the New World. This genius, which should bestow superiority, we have constantly curbed by the old traditional theory of economics and exploitation.”

America has therefore been torn, from its inception, between two opposing forces: “we have a competitive system coming down from the top, and a cooperative theory coming up from the very Earth beneath our feet. The struggle between these two forces is one of the greatest in the Western world, and that struggle must continue until the destiny or fate for which this continent was originally devised is fulfilled.”

And what is this fate? Manly Hall gives us the answer. He explains that here, in America,“must arise a model civilization: a civilization that will lure other nations to a similar way of living.”

To establish this model, “we must have the courage to break with traditional laws, to establish ourselves in our own way of life. We must do so harmoniously, cooperatively, and courageously.“

“It is here, on this Western continent, that a great world sociological experiment must take place. By a curious destiny, beyond human control, this continent demands, by reason of its vibratory forces, by the very archetypal pattern that caused this land to emerge from the primordial polar continent, that here the great economic experiment of the world must be played out. … Here, the theory of economics must finally be put in order.”

Put simply: modern man’s great initiation test must be played out here in America. And that’s what the Adversary ultimately represents: an initiation test.

From a philosophical standpoint, “Money is not the root of all evil; it is merely one of the little twigs on the tree of Cause and Effect.” It is an instrument of the Dharma in other words - a vehicle for man’s evolutionary destiny to be pursued and eventually achieved.

Hall teaches that “the economic problem is therefore not a supreme evil, it is a supreme challenge” - an initiatory test - “and the international nation cannot be developed from a possibility into an actuality until it is solved, nor can world peace be achieved.”

The challenge we now face, as this great collective initiation test comes to its culmination point, is to “restate, reestablish, and revitalize the great idealism of the world. We have got to restate in practical application the simple code upon which democracy was created: the Fatherhood of God and the Brotherhood of Man. Nothing can be worked out until that is accomplished.”

And it will not be accomplished until we begin this process first within ourselves. “There can be no path that leads to permanent peace except that which is founded upon self-conquest. This is the most difficult and arduous of all procedures in nature, and yet no individual who has not conquered himself can safely be entrusted with the guidance of others. The only individual fit to rule is the one who has ruled himself.”

To become self-ruling, you have to shed the individual Shadow tendencies within yourself that keep you tethered to the greater collective Shadow complex that is tyrannizing society as a whole. So long as wealth addiction, greed, competition, and other negative attributes of the “Adversary” linger within ourselves, we cannot truly be self-ruling individuals. Therefore, to overcome the challenge of our times, we must first rise to conquer these traits within ourselves.

As I state again and again, philosophy is the resource we need in order to successfully overcome the personal and collective trials and challenges we face.

We need it to be preached, and we need its message to be understood. This is really an education problem, and therefore “it is in the field of formal education that we should discover the creative power of divinity in the life of man.”

Manly Hall assures us that, here in America, “we have here the power to build soundly a way of life that can bind up the wounds of the world, and bring out of humanity’s chaos a great political, social, and economic commonwealth of peoples, united in every sense and freed forever from the threat of traditional exploitation policies.”

The power exists within us to make this ideal a reality: to bring about a better world; a new golden age.

The end of the Kali Yuga draws near, and the possibility for a new beginning is more real today than it ever has been. But Nature won’t drag us past this threshold kicking, screaming, and fighting against the self-transformation and rebirth we most need to experience. We must accomplish our own self-transformation ourselves, by a focused projection of our own will.

Our destiny is in our own hands. Let us come together and seize the moment. This is it. The time is now.

Thank you for sharing this comprehensive and exhaustive work. I'm still digesting it. I'm curious how you you weave in the California Gold Rush to the time frame immediately preceding the Civil War? Bringing that much new gold to the global market surely had consequences?

I came across this story about the Gold Rush while researching the history of Yellow Journalism. It focuses on the environmental damage of mining but shares many other interesting historical tidbits, including the national and international agendas of the Polk administration with respect to it. I suspect a new greenback issued under Lincoln wouldn't have been possible without the vast stores of gold in US vaults that was newly mined. Thoughts?

The Gold Rush: Behind the Hype

https://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=The_Gold_Rush:_Behind_the_Hype

Alexander, thank you for your body of work here. I can only imagine the amount of time and consideration it took. I read your entire Secret History of the 20th Century and found it an invaluable trove of information. You've compiled from some powerful informed and literate sources to create a behind-the-scenes world view that upturns the events we've taken for granted in our 'education' as fact. There's so much to digest in the series here that I must make my own summary, even a crib sheet. It certainly bears repeat readings.

Having said all that, I'm not sure I can get fully on board with your Rosicrucian globalist happy ending. While I acknowledge the notion of a 'hidden hand' and the esoteric aspect of life in general, it being a substrate of my own personal life, I sense a different future to the one you expound. As you wisely say, time will tell.

I look forward to delving into more of your work and who knows? Maybe I'll come around to the Rosy Cross. I certainly had a profound experience of divine maternal presence in the crypt of Rosslyn Chapel, one which will always remain with me.